How Nicolas Roeg (RIP) Used David Bowie, Mick Jagger & Art Garfunkel in His Mind-Bending Films

Critics have applauded Bradley Cooper for the bold move of casting Lady Gaga in his new remake of A Star Is Born, and as its titular star at that. As much cinematic daring as it takes to cast a high-profile musician in their first starring role in the movies, the act has its precedents, thanks not least to filmmaker Nicolas Roeg, who died last week. Having started out at the bottom of the British film industry, serving tea at London’s Marylebone Studios the year after World War II ended, he became a cinematographer (not least on David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia) and then a director in his own-right. That chapter of Roeg’s career began with 1970’s Performance, which he co-directed with Donald Cammell and in which he cast no less a rock star than Mick Jagger in his acting debut.

You can see Jagger in action in Performance’s trailer, which describes the picture as “a film about madness… madness and sanity. A film about fantasy. This is a film about fantasy and reality… and sensuality. A film about death… and life. This is a film about vice… and versa.”

Those words reflect something real about not just Performance itself — which crashes the end of the swinging 1960s into grim gangsterism in a manner that draws equally from Borges and Bergman — but Roeg’s entire body of work, and also the struggle that marketers went through to sell it to the public. But you don’t so much buy a ticket to see a Nicolas Roeg film as you buy a ticket to experience it, not least because of the particular performative qualities brought to the table by the music stars Roeg put onscreen.

In 1976 Roeg cast David Bowie as a space alien named Thomas Jerome Newton in the “shocking, mind-stretching experience in sight, in space, in sex” of The Man Who Fell to Earth, arguably the role he was born to play. “I thought of David Bowie when I first was trying to figure out who would be Mr. Newton, someone who was inside society and yet awkward in it,” Roeg says in the documentary clip above. “David got more than into the character of Mr. Newton. I think he put much more of himself than we’d been able to get into the script. It was linked very much to his ideas in his music, and towards the end, I realized a big change had happened in his life.” How much Bowie took from the role remains a matter for fans to discuss, though he himself admits to taking one thing in particular: the wardrobe. “I literally walked off with the clothes,” he says, “and I used the same clothes on the Station to Station tour.”

Even if stepping between the concert stage and the cinema screen looks natural in retrospect for the likes of Jagger and Bowie, can it work for a lower-key but nevertheless world-famous performer? Roeg’s 1980 film Bad Timing cast, in the starring role of an American psychiatrist in Cold War Vienna who grows obsessed with a young American woman, Art Garfunkel of Simon and Garfunkel. (Playing the woman, incidentally, is Theresa Russell, who would later show up in Roeg’s Insignificance in the role of Marilyn Monroe.) The clip above shows a bit of how Roeg uses the persona of Garfunkel, surely one of the least Dionysian among all 1960s musical icons, to infuse the character with a cerebral chill. In Roeg’s New York Times obituary, Garfunkel remembers — fondly — that the director “brought me to the edge of madness.” Roeg, for his part, had already paid his musician stars their compliments in that paper decades earlier: “The fact is that Jagger, Bowie and Garfunkel are all extremely bright, intelligent and well educated. A long way from the public stereotype.” But will any director use performers like them in quite the same way again?

Related Content:

Marilyn Monroe Explains Relativity to Albert Einstein (in a Nicolas Roeg Movie)

Watch David Bowie Star in His First Film Role, a Short Horror Flick Called The Image (1967)

When David Bowie Became Nikola Tesla: Watch His Electric Performance in The Prestige (2006)

Mick Jagger Acts in The Nightingale, a Televised Play from 1983

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...In 17th-Century Japan, Creaking Floors Functioned as Security Systems That Warned Palaces & Temples of Approaching Intruders and Assassins

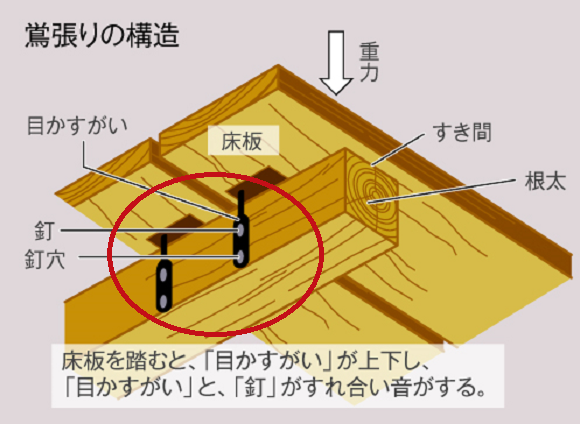

Offer a cutting-edge security system, and you’ll suffer no shortage of customers who want it installed. But before our age of concealed cameras, motion sensors, retinal scanners, and all the other advanced and often unsettling technologies known only to industry insiders, how did owners of large, expensive, and even royalty-housing properties buy peace of mind? We find one particularly ingenious answer by looking back about 400 years ago, to the wooden castles and temples of 17th-century Japan.

“For centuries, Japan has taken pride in the talents of its craftsmen, carpenters and woodworkers included,” writes Sora News 24’s Casey Baseel. “Because of that, you might be surprised to find that some Japanese castles have extremely creaky wooden floors that screech and groan with each step. How could such slipshod construction have been considered acceptable for some of the most powerful figures in Japanese history? The answer is that the sounds weren’t just tolerated, but desired, as the noise-producing floors functioned as Japan’s earliest automated intruder alarm.”

In these specially engineered floors, “planks of wood are placed atop a framework of supporting beams, securely enough that they won’t dislodge, but still loosely enough that there’s a little bit of play when they’re stepped on.” And when they are stepped on, “their clamps rub against nails attached to the beams, creating a shrill chirping noise,” rendering stealthy movement nearly impossible and thus making for an effective “countermeasure against spies, thieves, and assassins.”

According to Zen-Garden.org, you can still find — and walk on — four such uguisubari, or “nightingale floors,” in Kyoto: at Daikaku-ji temple, Chio-in temple, Toji-in temple, and Ninomura Palace.

If you can’t make it out to Kyoto any time soon, you can have a look and a listen to a couple of those nightingale floors in the short clips above. Then you’ll understand just how difficult it would have been to cross one without alerting anyone to your presence. This sort of thing sends our imaginations straight to visions of highly trained ninjas skillfully outwitting palace guards, but in their day these deliberately squeaky floors floors also carried more pleasant associations than that of imminent assassination. As this poem on Zen-Garden.org’s uguisubari page says says:

鳥を聞く

歓迎すべき音

鴬張りを渡る

A welcome sound

To hear the birds sing

across the nightingale floor

Related Content:

Omoshiroi Blocks: Japanese Memo Pads Reveal Intricate Buildings As The Pages Get Used

A Virtual Tour of Japan’s Inflatable Concert Hall

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Illustrated Version of “Alice’s Restaurant”: Watch Arlo Guthrie’s Thanksgiving Counterculture Classic

Alice’s Restaurant. It’s now a Thanksgiving classic, and something of a tradition around here. Recorded in 1967, the 18+ minute counterculture song recounts Arlo Guthrie’s real encounter with the law, starting on Thanksgiving Day 1965. As the long song unfolds, we hear all about how a hippie-bating police officer, by the name of William “Obie” Obanhein, arrested Arlo for littering. (Cultural footnote: Obie previously posed for several Norman Rockwell paintings, including the well-known painting, “The Runaway,” that graced a 1958 cover of The Saturday Evening Post.) In fairly short order, Arlo pleads guilty to a misdemeanor charge, pays a $25 fine, and cleans up the thrash. But the story isn’t over. Not by a long shot. Later, when Arlo (son of Woody Guthrie) gets called up for the draft, the petty crime ironically becomes a basis for disqualifying him from military service in the Vietnam War. Guthrie recounts this with some bitterness as the song builds into a satirical protest against the war: “I’m sittin’ here on the Group W bench ’cause you want to know if I’m moral enough to join the Army, burn women, kids, houses and villages after bein’ a litterbug.” And then we’re back to the cheery chorus again: “You can get anything you want, at Alice’s Restaurant.”

We have featured Guthrie’s classic during past years. But, for this Thanksgiving, we give you the illustrated version. Happy Thanksgiving to everyone who plans to celebrate the holiday today.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs Reads His Sarcastic “Thanksgiving Prayer” in a 1988 Film By Gus Van Sant

Marilyn Monroe’s Handwritten Turkey-and-Stuffing Recipe

William Shatner Raps About How to Not Kill Yourself Deep Frying a Turkey

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 13 Tips for What to Do with Your Leftover Thanksgiving Turkey

Read More...The Making of “Bohemian Rhapsody”: Take a Deep Dive Into the Iconic Song with Queen’s 2002 Mini Documentary

Despite being fraught with production difficulties, an absent director, and a critical quibbling over its sexuality politics, Bohemian Rhapsody, the biopic of Freddie Mercury and Queen, has been doing very well at the box office. And though it has thrust Queen’s music back into the spotlight, has it even really gone away?

The song itself, the 6 minute epic “Bohemian Rhapsody,” was the top of the UK singles charts for nine weeks upon its release and hasn’t been forgotten since. It’s part of our collective DNA, but with a certain caveat…it’s notoriously difficult to cover. It is so finely constructed that it can’t be deconstructed, leaving artists to stand in the shadow of Mercury’s delivery. Brian May, in the above video, gives credit to Axl Rose for getting close to the powerful high registers of Mercury, but even that was a kind of karaoke. And let’s not even talk about Kanye West’s stab at it.

So it’s a good time to check in with this 45 minute-long mini-doc on the making of the song, which took the band into the stratosphere. Produced in 2002 for the band’s Greatest Hits DVD, it features guitarist Brian May and drummer Roger Taylor. The first part is on the writing of the song, the second part on the making of the music video, and the third, the bulk of the doc, on the production.

Don’t expect any explanation of the subject matter of the song–as May says, Mercury would have shrugged off any interpretation and dismissed any search for depth. And while Mercury always took care over his lyrics, the power is all there in the music.

As for the video, that came about from necessity, as the band wanted to be on Top of the Pops and tour at the same time. By using their rehearsal stage at Elstree studios for the performance footage and a side area for the choral/close-up segments, they made a strangely iconic video. (Who doesn’t think of Queen’s four members arranged in a diamond when those vocals start up?). The two main effects were a prism lens on the camera and video feedback, all done live.

The last part is fascinating and a deep dive into the mix. Brian May, alongside studio engineer Justin Shirley Smith, play just the piano, bass, and drums from the song at first. Mercury was a self-taught pianist who played “like a drummer,” with a metronome in his head, says May.

The guitarist also isolates his various guitar parts, including the harmonics during the opening ballad portion, the “shivers down my spine” sound made by scraping the strings, and the famous solo, which he wrote as a counterpoint to Mercury’s melody. It’s geekery of the highest order, but it’s for a song that deserves such attention.

Inside The Rhapsody will be added to our collection of Free Documentaries, a subset of our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

What Made Freddie Mercury the Greatest Vocalist in Rock History? The Secrets Revealed in a Short Video Essay

Hear Freddie Mercury & Queen’s Isolated Vocals on Their Enduring Classic Song, “We Are The Champions”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Read More...Watch the First Film Adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1910): It’s Newly Restored by the Library of Congress

In his Critique of Judgment Immanuel Kant made every attempt to separate the Sublime—the phenomenon that inspires reverence, awe, and imagination—from terror, horror, and monstrosity. But as Barbara Freeman argues, the distinctions fall apart. Nowhere do we see this better dramatized, Freeman writes, than in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which “can be read almost as a parody of the Critique of Judgment, for in it everything Kant identifies with or as sublime… yield precisely what Kant prohibits: terror, monstrosity, passion, and fanaticism.”

Reason, even that as careful as Kant’s, begets monsters, Shelley suggests. It’s a theme that has become so commonplace in writing about Frankenstein and its numerous progeny that it seems hardly worth repeating. And yet, Shelley’s dark vision, like that of her contemporary Francisco Goya, came at a time when electricity was a new force in the world (one that her husband Percy used to conduct experiments on himself)… a time when Kant’s philosophy had seemingly validated empirical realism and the primacy of abstract reason.

Steeped in the latest science and philosophy, and living on the other side of the French Revolution, Shelley saw the return of what Kant had sought to banish. The monster arrives as an ominous portent of atrocity. As Steven J. Kraftchick points out in a recent anthology of Frankenstein essays published for the novel’s 200th anniversary, “the English term ‘monster’ (by way of French) likely derives from the Latin words montrare ‘to demonstrate’ and monere ‘to warn.’” The monster comes to show “the limits of the ordinary… expanding or contracting.”

As a being intended to show us something, it seems apt that Victor Frankenstein’s creation became ubiquitous in film and television, first arriving on screen in 1910 at the dawning of film as a popular medium. The first Frankenstein adaptation predates the technological horrors of the 20th century (themselves, of course, well documented on film). Rather than taking technology to task directly, this original cinematic adaptation, directed by J. Searle Dawley for Thomas Edison’s studios, vaguely illustrates, as Rich Drees writes, “the dangers of tampering in God’s realm.”

It was a trite message tailored for censorious moral reformers who had taken aim at the moving image’s supposedly corrupting effect on impressionable minds. And yet the film does more than inaugurate a cinematic tradition of better Frankenstein adaptations, both faithful and liberally modernized. The creation of the monster in the 13-minute short is somewhat terrifying—and certainly would have unsettled audiences at the time. Significantly, it takes place in giant black box, with a small window through which Victor peers as the special effects unfold.

The scene is not unlike a film director looking through a colossal camera’s lens, further suggesting the dangerous influence of film, its ability to produce and capture monstrosities. The Library of Congress’s Mike Mashon describes the Edison production of Frankenstein as not “all that revelatory.” Maybe with the benefit of 108 years of hindsight, it is not. But as a critique of the very technology that produced it, we can see it updating Shelley’s anxieties, anticipating the ways in which Frankenstein-like stories have come to telegraph fears of computer intelligence, in films increasingly created by intelligent machines.

This 1910 Frankenstein film has been restored by the Library of Congress, and Mashon’s story of how the only nitrate print was acquired by the library’s Packard Campus for Audio Visual Conservation may be, he writes, “more interesting than the film itself.” Or it may not, depending on your level of interest in the twists and turns of library acquisitions. But the film, which you can see in its restored glory at the top, rewards viewing as more than a cinema-historical artifact. Its effects are crude, its simplified story moralistic, but this truncated version cannily recognizes the horrific creature not as the excluded other but as the monstrous mirror image of its creator.

via Indiewire

Related Content:

Mary Shelley’s Handwritten Manuscripts of Frankenstein Now Online for the First Time

The First Horror Film, George Méliès’ The Manor of the Devil (1896)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Marxism by Raymond Geuss: A Free Course

This course taught by Raymond Geuss was originally presented at Cambridge University in 2013. All 8 lectures can be streamed above, or on YouTube here. “Marxism” has been added to our collection of 170 Free Philosophy Courses, a subset of our larger collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Read More...7 Tips From Ernest Hemingway on How to Write Fiction

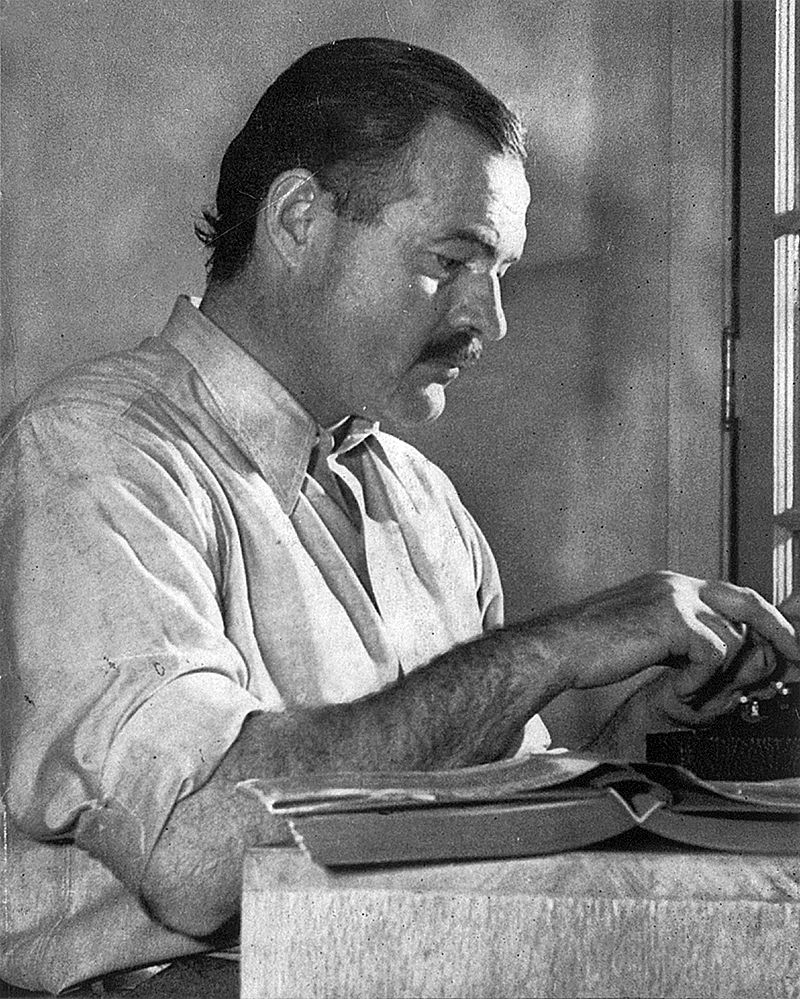

Image by Lloyd Arnold via Wikimedia Commons

Before he was a big game hunter, before he was a deep-sea fisherman, Ernest Hemingway was a craftsman who would rise very early in the morning and write. His best stories are masterpieces of the modern era, and his prose style is one of the most influential of the 20th century.

Hemingway never wrote a treatise on the art of writing fiction. He did, however, leave behind a great many passages in letters, articles and books with opinions and advice on writing. Some of the best of those were assembled in 1984 by Larry W. Phillips into a book, Ernest Hemingway on Writing.

We’ve selected seven of our favorite quotations from the book and placed them, along with our own commentary, on this page. We hope you will all–writers and readers alike–find them fascinating.

1: To get started, write one true sentence.

Hemingway had a simple trick for overcoming writer’s block. In a memorable passage in A Moveable Feast, he writes:

Sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, I would sit in front of the fire and squeeze the peel of the little oranges into the edge of the flame and watch the sputter of blue that they made. I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say. If I started to write elaborately, or like someone introducing or presenting something, I found that I could cut that scrollwork or ornament out and throw it away and start with the first true simple declarative sentence I had written.

2: Always stop for the day while you still know what will happen next.

There is a difference between stopping and foundering. To make steady progress, having a daily word-count quota was far less important to Hemingway than making sure he never emptied the well of his imagination. In an October 1935 article in Esquire ( “Monologue to the Maestro: A High Seas Letter”) Hemingway offers this advice to a young writer:

The best way is always to stop when you are going good and when you know what will happen next. If you do that every day when you are writing a novel you will never be stuck. That is the most valuable thing I can tell you so try to remember it.

3: Never think about the story when you’re not working.

Building on his previous advice, Hemingway says never to think about a story you are working on before you begin again the next day. “That way your subconscious will work on it all the time,” he writes in the Esquire piece. “But if you think about it consciously or worry about it you will kill it and your brain will be tired before you start.” He goes into more detail in A Moveable Feast:

When I was writing, it was necessary for me to read after I had written. If you kept thinking about it, you would lose the thing you were writing before you could go on with it the next day. It was necessary to get exercise, to be tired in the body, and it was very good to make love with whom you loved. That was better than anything. But afterwards, when you were empty, it was necessary to read in order not to think or worry about your work until you could do it again. I had learned already never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it.

4: When it’s time to work again, always start by reading what you’ve written so far.

T0 maintain continuity, Hemingway made a habit of reading over what he had already written before going further. In the 1935 Esquire article, he writes:

The best way is to read it all every day from the start, correcting as you go along, then go on from where you stopped the day before. When it gets so long that you can’t do this every day read back two or three chapters each day; then each week read it all from the start. That’s how you make it all of one piece.

5: Don’t describe an emotion–make it.

Close observation of life is critical to good writing, said Hemingway. The key is to not only watch and listen closely to external events, but to also notice any emotion stirred in you by the events and then trace back and identify precisely what it was that caused the emotion. If you can identify the concrete action or sensation that caused the emotion and present it accurately and fully rounded in your story, your readers should feel the same emotion. In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway writes about his early struggle to master this:

I was trying to write then and I found the greatest difficulty, aside from knowing truly what you really felt, rather than what you were supposed to feel, and had been taught to feel, was to put down what really happened in action; what the actual things were which produced the emotion that you experienced. In writing for a newspaper you told what happened and, with one trick and another, you communicated the emotion aided by the element of timeliness which gives a certain emotion to any account of something that has happened on that day; but the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always, was beyond me and I was working very hard to get it.

6: Use a pencil.

Hemingway often used a typewriter when composing letters or magazine pieces, but for serious work he preferred a pencil. In the Esquire article (which shows signs of having been written on a typewriter) Hemingway says:

When you start to write you get all the kick and the reader gets none. So you might as well use a typewriter because it is that much easier and you enjoy it that much more. After you learn to write your whole object is to convey everything, every sensation, sight, feeling, place and emotion to the reader. To do this you have to work over what you write. If you write with a pencil you get three different sights at it to see if the reader is getting what you want him to. First when you read it over; then when it is typed you get another chance to improve it, and again in the proof. Writing it first in pencil gives you one-third more chance to improve it. That is .333 which is a damned good average for a hitter. It also keeps it fluid longer so you can better it easier.

7: Be Brief.

Hemingway was contemptuous of writers who, as he put it, “never learned how to say no to a typewriter.” In a 1945 letter to his editor, Maxwell Perkins, Hemingway writes:

It wasn’t by accident that the Gettysburg address was so short. The laws of prose writing are as immutable as those of flight, of mathematics, of physics.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in February 2013.

Related content:

Writing Tips by Henry Miller, Elmore Leonard, Margaret Atwood, Neil Gaiman & George Orwell

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer (1934)

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

James Joyce Picked Drunken Fights, Then Hid Behind Ernest Hemingway

Find Courses on Hemingway and Other Authors in our big list of Free Online Courses

Read More...How Glenn Gould’s Eccentricities Became Essential to His Playing & Personal Style: From Humming Aloud While Playing to Performing with His Childhood Piano Chair

The cultural law that we must indulge, or at least tolerate, the quirks of genius has much less force these days than it once did. Notoriously perfectionistic Stanley Kubrick’s fabled fits of verbal abuse, for example, might skirt a line with actors and audiences now, though it’s hard to argue with the results of his process. Many other examples of artists’ bad behavior need no further mention, they are now so well-known and rightly reviled. When it comes to another legendarily demanding auteur, Glenn Gould was as devoted to his art, and as doggedly idiosyncratic, as it gets.

But the case of Gould presents us with a very different picture than that of the artist who lashes out at or abuses those around him. His eccentricities consisted mainly of hermetic habits, odd attachments, and a tendency to hum and sing loudly while he played Bach, Mozart, Schoenberg, or any number of other classical composers whose work he re-interpreted. While Leonard Bernstein praised Gould as a “thinking performer” (one with whom Bernstein sharply disagreed), he was also a particularly noisy performer, a fact that bedeviled recording engineers.

As music critic Tim Page says in the interview clip at the top, the habit of humming also troubled Gould, who saw it as a liability but could not play at his best without doing it. “I would say that Glenn was in sort of an ecstatic transport,” during a lot of his performances. “When you look at him, he’s almost auto-erotic…. He is clearly having a major and profound reaction to it as he is also making it happen.” The trait manifested “from the beginning” of Gould’s life, his father Bert once said. “When you’d expect a child to cry, Glenn would always hum.” (He may or may not have had Asperger’s syndrome.)

“On the warm summer day of the first recording session” of his first recording of Bach’s Goldberg Variations, writes Edward Rothstein at The New York Times:

He arrived at the recording studio wearing a winter coat, a beret, a muffler and gloves. He carried a batch of towels, bottles of spring water, several varieties of pills and a 14-inch high piano chair to sit on. He soaked his arms in hot water for 20 minutes, took several medications, adjusted each leg of his chair, and proceeded to play, loudly humming and singing along. After a week, he had produced one of the most remarkable performances of Bach’s Goldberg Variations on record.

See a young Gould further up play J.S. Bach’s Partita #2, loudly humming and singing expressively as though it were an opera. Another of Gould’s incurable quirks also threatened to be a detriment to his performances, especially after he renounced performing live and retreated permanently to the studio. Gould insisted on performing for over 21 years on a “chair that has become an object of reverence for Gould devotees,” explains the podcast Ludwig van Toronto. Gould was “obsessed” with the chair and “wouldn’t perform on anything else.”

In the video above, you can see Gould defend the diminutive chair—built by his father for his childhood practice—telling a TV presenter, “I’ve never given any concert in anything else.” The chair, he says, is “a member of the family! It is a boon companion, without which I do not function, I cannot operate.”

Along with his exactly specified height for the piano, over which he hovered with his chin just inches from the middle C, a rug under his feet, and a very warm studio, which he often sat in wearing winter clothes, Gould’s chair is one of the most distinctive of his oddities. The chair is “one of the most famous musical objects in the history of classical music,” Kate Shapero writes at Gould interview site Unheard Notes. But it caused considerable consternation in the studio.

Now residing in a glass case at the National Library of Canada, Gould’s chair is so dilapidated that “the only thing that kept it from falling apart,” says Ludwig van Toronto, “is some duct tape, screws, and piano wire.” Even before it acquired the noisy hardware of the metal brackets holding up its two front legs, Gould’s animated playing made the chair rock and creak in distracting ways. But while Gould’s unintentional accompaniments turn some people off, his true fans, and they are multitude, either find his vocalizations charming or completely tune them out. (They disappear when he begins performing above.)

Gould’s “singing authenticates and humanizes his performances,” composer Luke Dahn argues. “It reveals a performer so entirely absorbed in the music’s moment and reminds us that this is a performance, even if within the confines of the studio.” His unusual qualities “distinguish his recordings from those of countless note-perfect recordings available today that take on a fabricated, sterile, and even robotic quality. (Is perfection ever very interesting?)” Like the greatest musical innovators—John Coltrane especially comes to mind—Gould has wide appeal both inside his genre circles and far outside them.

“I can put him on for hours,” says noted Gould devotee John Waters, “he’s like nobody else. He was the ultimate original—a real outsider. And he had a great style, the hats and the gloves and so on.” Whatever the origins of Gould’s quirks, and whatever his misgivings about them, Gould lovers perceive them not as flaws to be overlooked or tolerated but essential qualities of his passion and utterly unique personal style. See him “say something original” about Beethoven above, then deliver a tremendous performance, mostly hum free but totally enthralling, of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 17 in D Minor—a piece whose nickname captures Gould’s musical effect: “The Tempest.”

Related Content:

Listen to Glenn Gould’s Shockingly Experimental Radio Documentary, The Idea of North (1967)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...R.I.P. Stan Lee: Take His Free Online Course “The Rise of Superheroes and Their Impact On Pop Culture”

“I grew up in an exurb where it took nearly an hour to walk to the nearest shop, to the nearest place to eat, to the library,” remembers writer Adam Cadre. “And the steep hills made it an exhausting walk. That meant that until I turned sixteen, when school was not in session I was stuck at home. This was often not a good place to be stuck. Stan Lee gave me a place to hang out.” Many other former children of exurban America — as well as everywhere else — did much of their growing up there as well, not just in the universe of Marvel Comics but in those of the comics and other forms of culture to which it gave rise or influenced, most of them either directly or indirectly shaped by Lee, who died yesterday at the age of 95.

“His critics would say that for me to thank Stan Lee for creating the Marvel Universe shows that I’ve fallen for his self-promotion,” Cadre continues, “that it was Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko and his other collaborators who supplied the dynamic, expressive artwork and the epic storylines that made the Marvel Universe so compelling.”

Marvel fans will remember that Ditko, co-creator with Lee of Spider-Man and Doctor Strange, died this past summer. Kirby, whose countless achievements in comics include co-creating the Fantastic Four, the X‑Men, and the Hulk with Lee, passed away in 1994. (Kirby’s death, as I recall, was the first I’d ever heard about on the internet.)

Those who take a dimmer view of Lee’s career see him as having done little more artistic work than putting dialogue into the speech bubbles. But like no small number of other Marvel Universe habitués, Cadre “didn’t read superhero comics for the fights or the costumes or the trips to Asgard and Attilan. I read them for fantasy that read like reality, for the interplay of wildly different personalities — and for the wisecracks.” And what made superhero stories the right delivery system for that interplay of personalities and those wisecracks? You’ll find the answer in “The Rise of Superheroes and Their Impact On Pop Culture,” an online course from the Smithsonian, previously featured here on Open Culture and still available to take at your own pace in edX’s archives, created and taught in part by Lee himself. You can watch the trailer for the course at the top of the post.

If you take the course, its promotional materials promise, you’ll learn the answers to such questions as “Why did superheroes first arise in 1938 and experience what we refer to as their “Golden Age” during World War II?,” “How have comic books, published weekly since the mid-1930’s, mirrored a changing American society, reflecting our mores, slang, fads, biases and prejudices?,” and “When and how did comic book artwork become accepted as a true American art form as indigenous to this country as jazz?” Whether or not you consider yourself a “true believer,” as Lee would have put it, there could be few better ways of honoring an American icon like him than discovering what makes his work in superhero comics — the field to which he dedicated his life, and the one which has taken more than its fair share of derision over the decades — not just a reflection of the culture but a major influence on it as well.

Enroll in “The Rise of Superheroes and Their Impact On Pop Culture” here.

Related Content:

1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities

The Great Stan Lee Reads Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven”

Download Over 22,000 Golden & Silver Age Comic Books from theComic Book Plus Archive

Download 15,000+ Free Golden Age Comics from the Digital Comic Museum

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

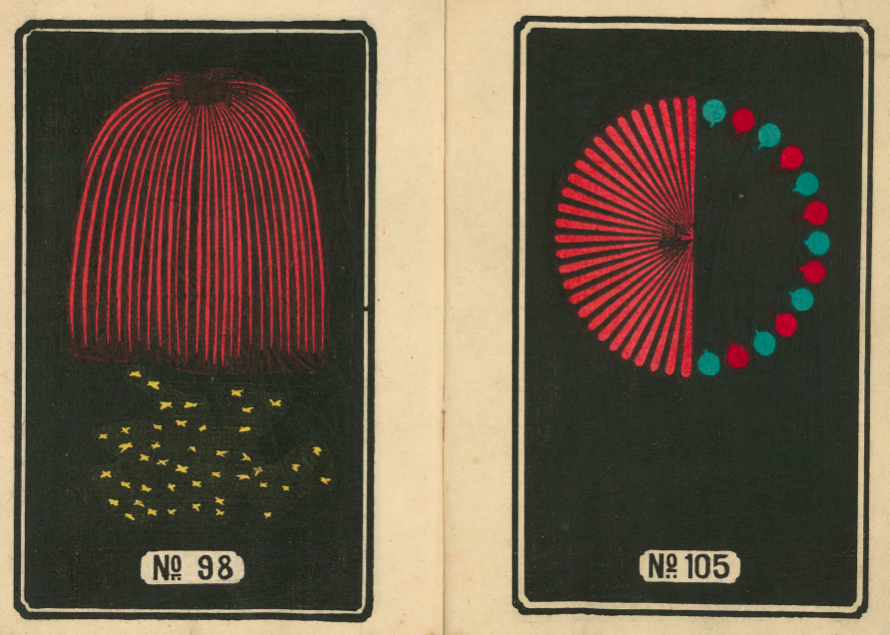

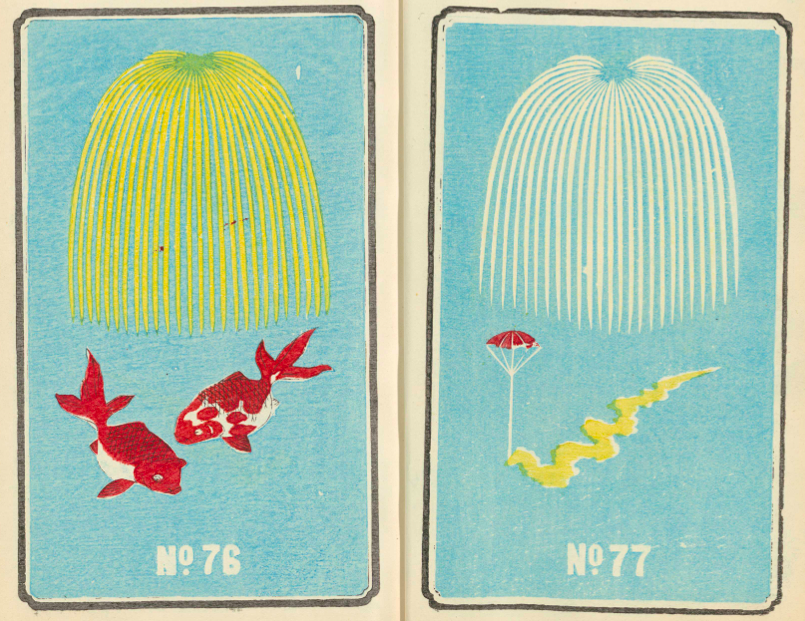

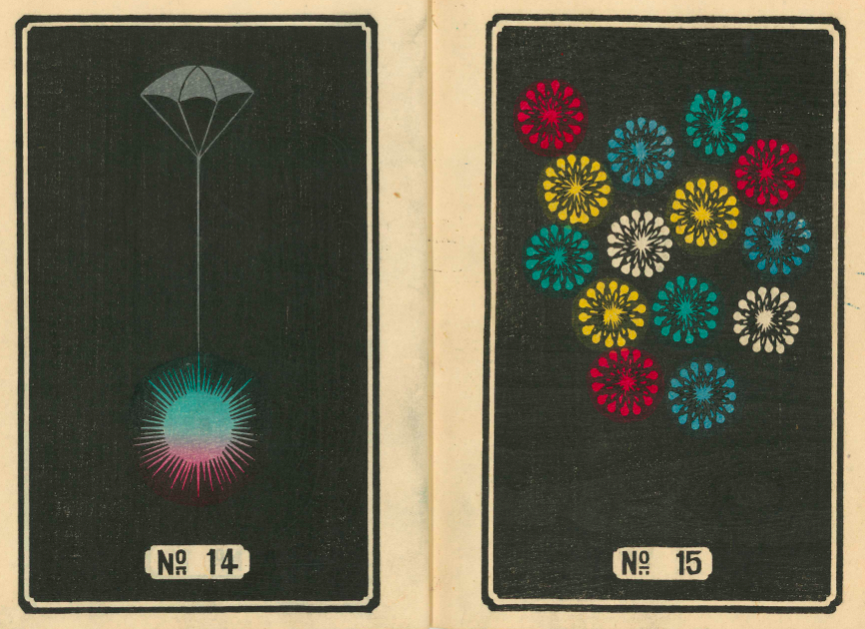

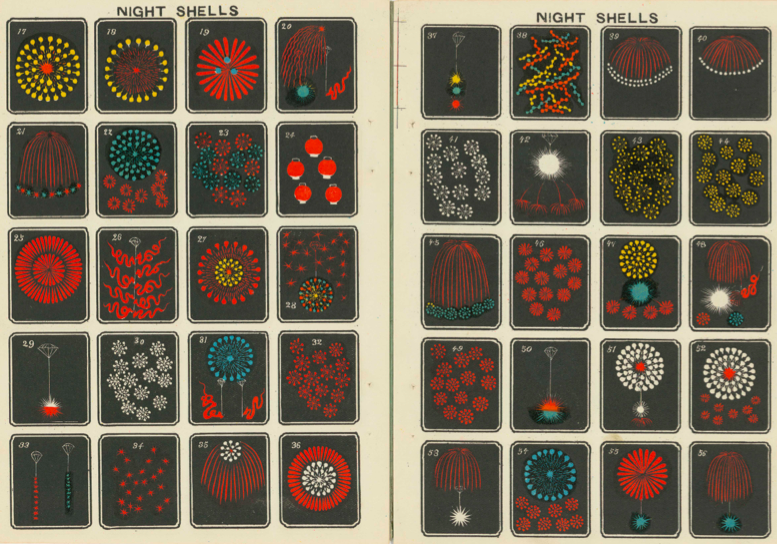

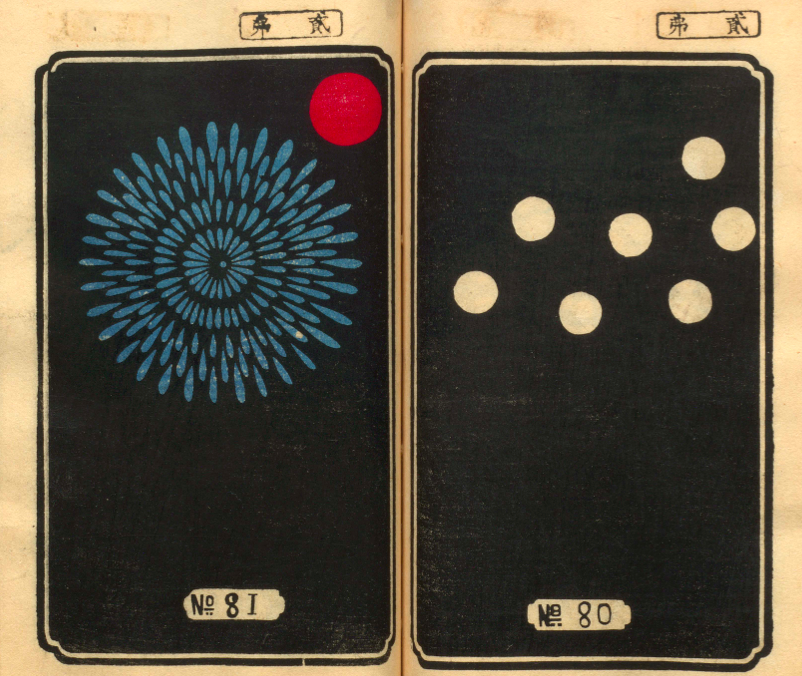

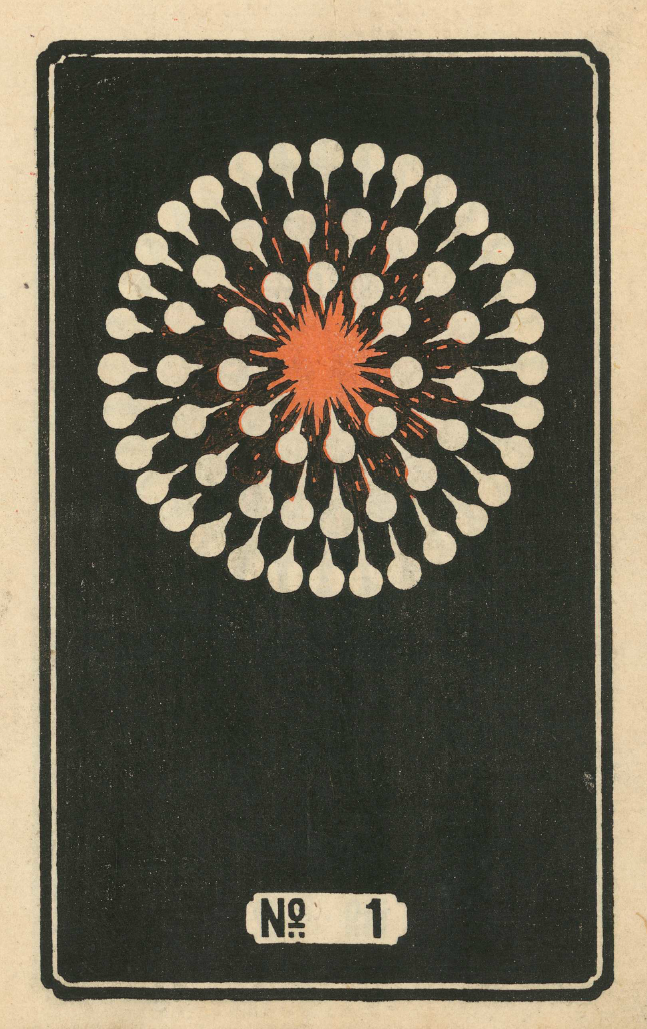

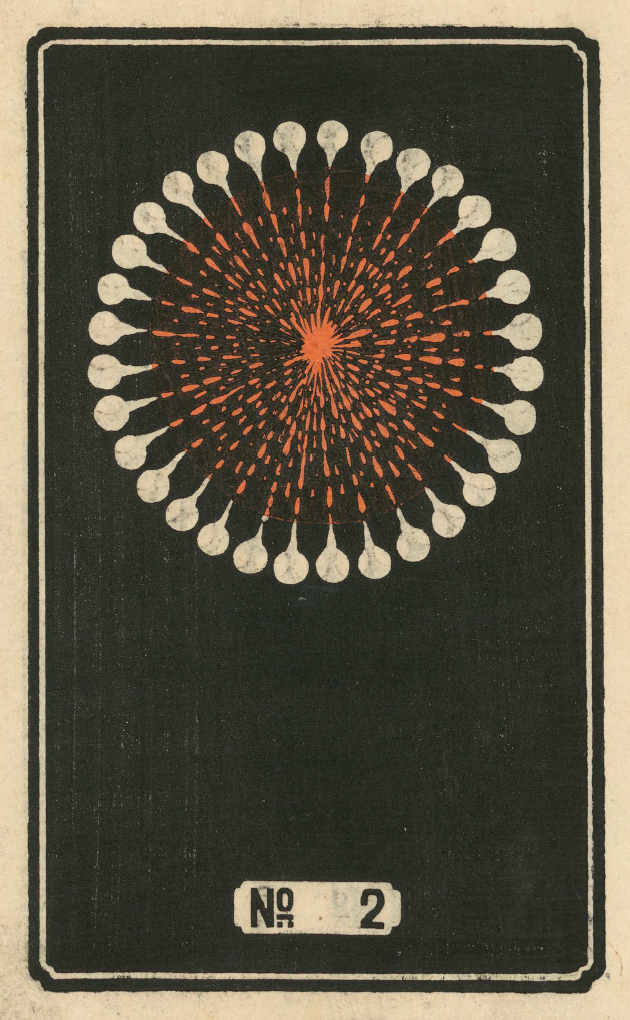

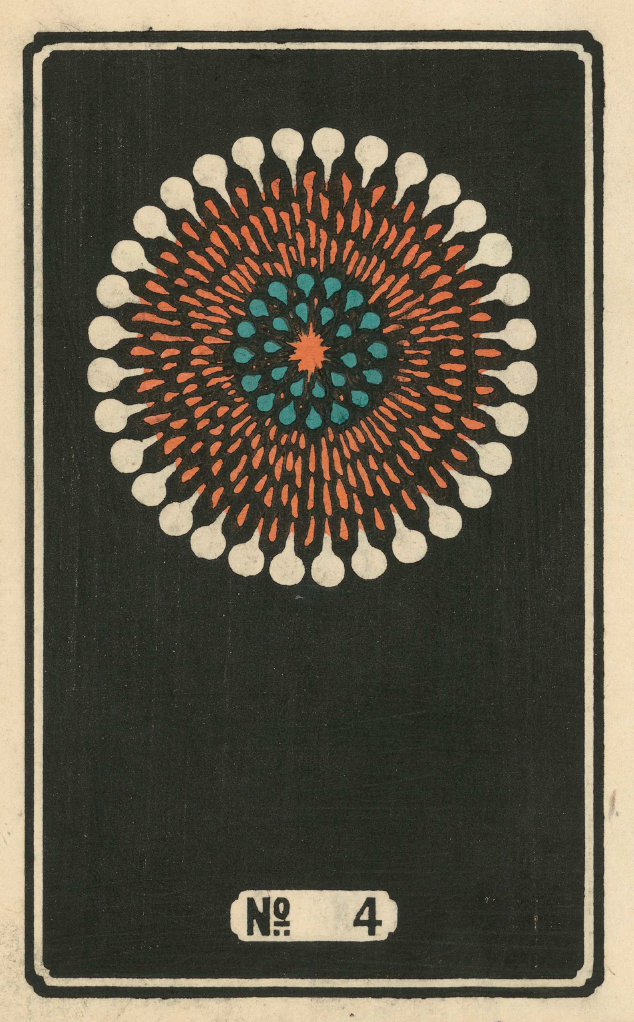

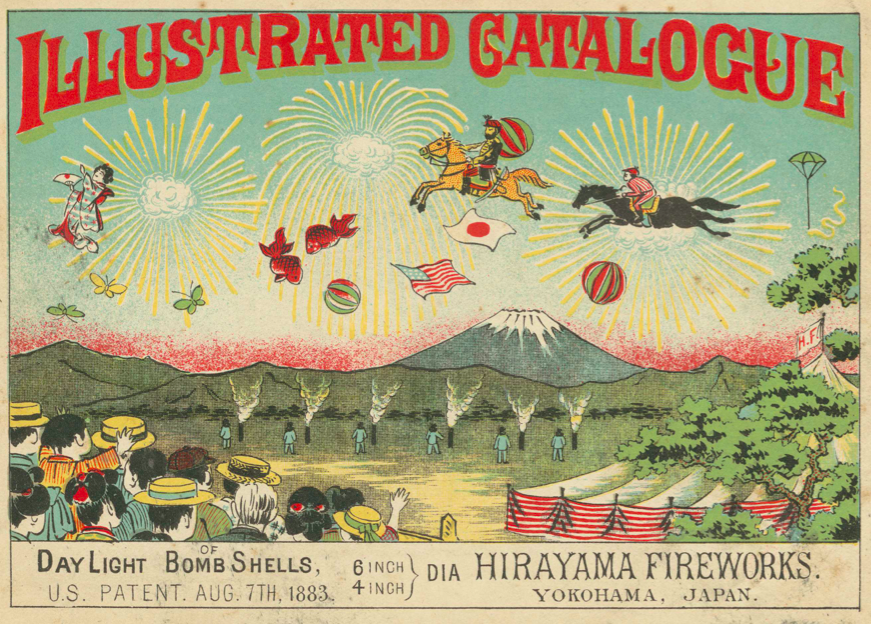

Read More...Hundreds of Wonderful Japanese Firework Designs from the Early-1900s: Digitized and Free to Download

The Japanese term for fireworks, hanabi (花火), combines the words for fire, bi (火), and flower, hana (火). If you’ve seen fireworks anywhere, that derivation may seem at least vaguely apt, but if you’ve seen Japanese fireworks, it may well strike you as evocative indeed. The traditional Japanese way with presenting flowers, their shapes and colors as well as their scents, has something in common with the traditional Japanese way of putting on a fireworks show.

Not that the production of firecrackers goes as far back, historically, as the arrangement of flowers does, nor that firecrackers themselves, originally a product of China, have anything essentially Japanese about them.

But as more recently with cars, comic books, consumer electronics, and Kit-Kats, whenever Japan re-interprets a foreign invention, the project amounts to radical re-invention, and often a dazzling one at that.

These Japanese versions of non-Japanese things often become highly desirable around the world in their own right. It certainly happened with Japanese fireworks, here proudly displayed in these elegant and vividly colored English catalogs of Hirayama Fireworks and Yokoi Fireworks, published in the early 1900s by C.R. Brock and Company, whose founding date of 1698 makes it the oldest firework concern in the United Kingdom.

These Brocks catalogs been digitized by the Yokohama Board of Education and made available online at the Internet Archive. Though I’ve never seen a fireworks show in Yokohama, that city, dotted as it is with impeccably designed public gardens, certainly has its flower-appreciation credentials in order.

Organized into such categories as “Vertical Wheels,” “Phantom Circles,” and “Colored Floral Bomb Shells,” the catalogs present their imported Japanese wares simply, as various patterns of color against a black or blue background. But simplicity, as even those only distantly acquainted with Japanese art have seen, supports a few particularly strong and enduring branches of Japanese aesthetics.

No matter where you take in your displays of fireworks, you’ll surely recognize more than a few of these designs from having seen them light up the night sky. And as far as where to look for the next firework innovator, I might suggest South Korea, where I live: at this past summer’s Seoul International Fireworks festival I witnessed fireworks exploding into the shape of cat faces, whiskers and all. Such elaborateness many violate the more rigorous versions of the Japanese sensibility as they apply to hanabi — but then again, just imagine what wonders Japan, one of the most cat-loving countries in the world, could do with that concept.

Related Content:

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...