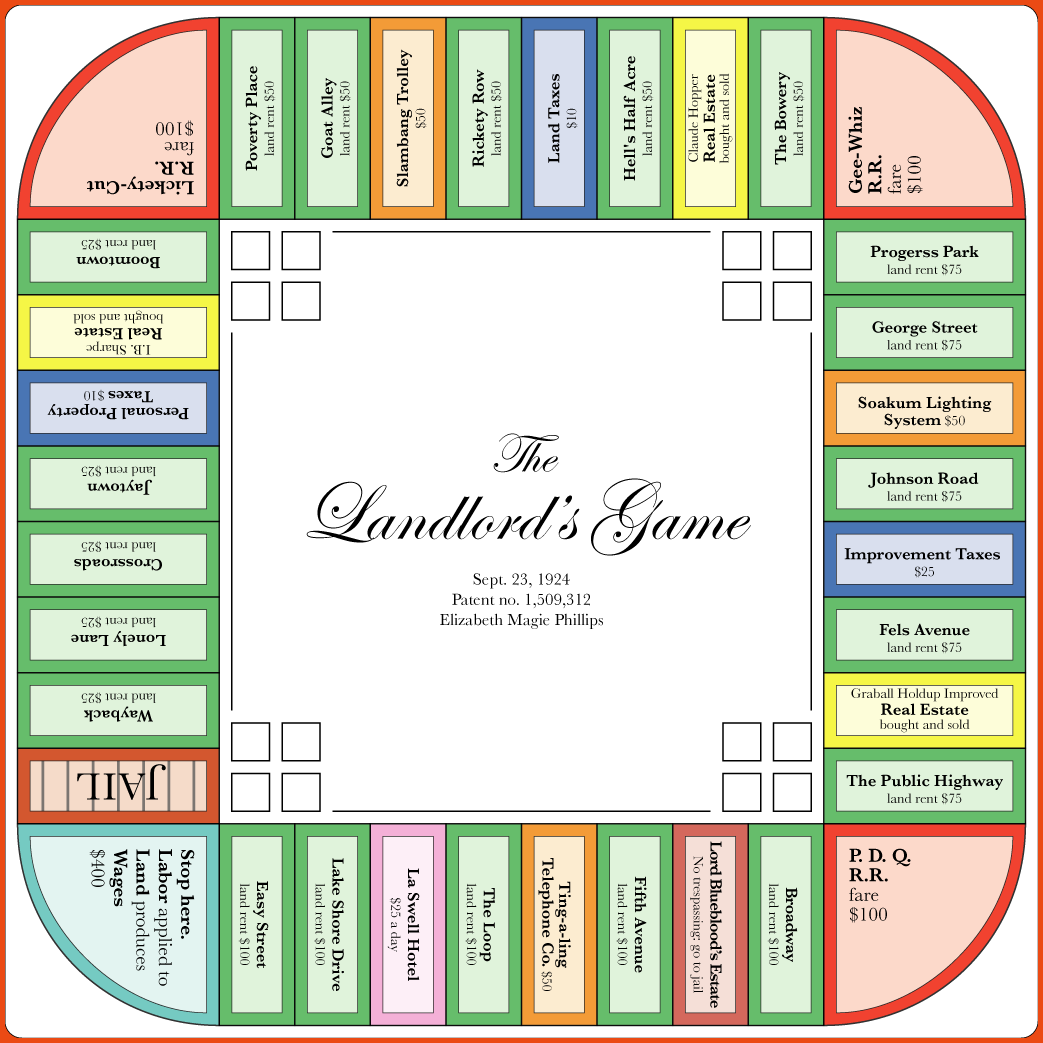

As much as any contemporary writer of literary fiction ever does, Junot Díaz has become something of a household name in the years since his debut novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao appeared in 2007, then went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, among other many other honors. The novel has recently topped critics lists of the best 21st century novels (so far), and the recognition is well-deserved, and very hard-won. Díaz spent a decade writing the book, his process, in the words of The New York Times’ Sam Anderson, “notoriously slow” and laborious. But none of his time working on Oscar Wao, it seems, was spent idle. During the long gestation period between his first book of stories, 1996’s Drown, his first novel, and the many accolades to follow, Diaz has reliably turned out short stories for the likes of The New Yorker, culminating in his most recent collection from 2012, This Is How You Lose Her.

Díaz is his own worst critic—even he admits as much, calling his overbearing critical self “a character defect” and “way too harsh.” Perhaps one of the reasons he finds his process “miserable” is that his “narrative space,” as critic Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert writes, consists not of “nostalgic recreations of idealized childhood landscapes,” but rather the “bleak, barren, and decayed margins of New Jersey’s inner cities,” as well as the tragic, bloody past of his native Dominican Republic.

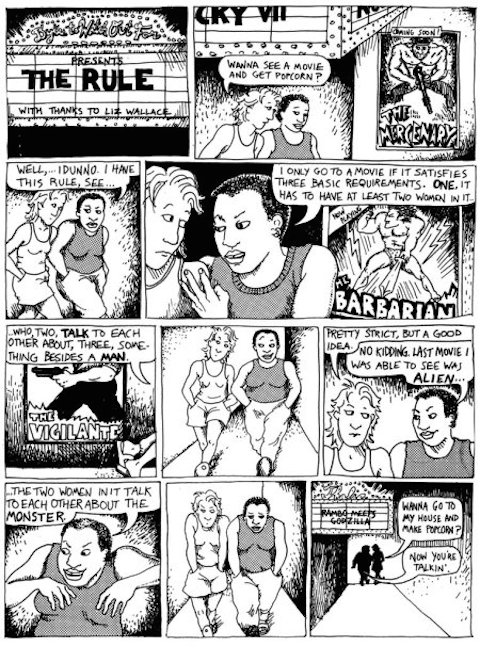

Despite the historical violence from which his characters emerge, the voices of Diaz’s narratives are a vital force, full of lightening-fast recall of pop cultural touchstones, hip-hop, historic and folkloric allusions, and the minutiae of high geekery, from sci-fi film, to gaming, to comic book lore. (Watch Diaz discuss geek culture at New York’s St. Mark’s Comics above.)

Like a nerdy New World Joyce, Díaz works in a dizzying swirl of references that critic and playwright Gregg Barrios calls a “deft mash-up of Dominican history, comics, sci-fi, magic realism and footnotes.” The writer’s unique idiom—swinging with ease from the most streetwise and profane vernacular to the most formal academic prose and back again—interrogates categories of gender and national identity at every turn, asking, writes Barrios, “Who is American? What is the American experience?” Diaz’s narrative voice—described by Leah Hager Cohen as one of “radical inclusion”—provides its own answers.

That notoriously slow process pays dividends when it comes to fully-realized characters who seem to live and breathe in a space outside the page, a consequence of Díaz “sitting with my characters” for a long time, he tells Cressida Leyshon, “before I can write a single word, good or bad, about them. I seem to have to make my characters family before I can access their hearts in any way that matters.” You can read the results of all that sitting and agonizing below, in seven stories that are available free online, in text and audio. Stories with an asterisk next to them appear in This Is How You Lose Her. The final story comes from Diaz’s first collection, Drown.

- “The Cheater’s Guide to Love” * (The New Yorker, July 2012—text, audio)

- “Monstro” (The New Yorker, June 2012—text)

- “Miss Lora” * (The New Yorker, April 2012—text)

- “The Pura Principle” * (The New Yorker, March 2010—text)

- “Alma” * (The New Yorker, December 2007—text, audio)

- “Wildwood” (The New Yorker, June 2007—text)

- “How to date a brown girl (black girl, white girl, or halfie)” (text, audio)

Related Content:

1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for FreeJunot Díaz Annotates a Selection of The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao for “Poetry Genius”

Read 18 Short Stories From Nobel Prize-Winning Writer Alice Munro Free Online

800 Free eBooks for iPad, Kindle & Other Devices

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness