This weekend, an estimated 20,000 agnostics, atheists and ardent secularists gathered on the National Mall in rainy Washington DC. They were attending the first Reason Rally, an event intended to “unify, energize, and embolden secular people nationwide, while dispelling the negative opinions held by so much of American society… and having a damn good time doing it!” Lawrence Krauss, Michael Shermer, Eddie Izzard — they all spoke to the crowd. And then came Richard Dawkins, the high priest of reason, the author of The Selfish Gene, who spent decades teaching evolutionary biology at Oxford. In the middle of his 16 minute talk, he tells the audience, “We’re here to stand up for reason, to stand up for science, to stand up for logic, to stand up for the beauty of reality, and the beauty of the fact that we can understand reality.” I’m with you Richard on that. But then comes the scorn we’re now so accustomed to (“I don’t despise religious people; I despise what they stand for.”), and my guess is that changing perceptions of agnostics, atheists and secularists will need to wait for another day.

Newly Discovered Piece by Mozart Performed on His Own Fortepiano

A music scholar made an astounding discovery recently while going through the personal belongings from the attic of a recently deceased church musician and band leader in the Lech Valley of the Austrian Tyrol.

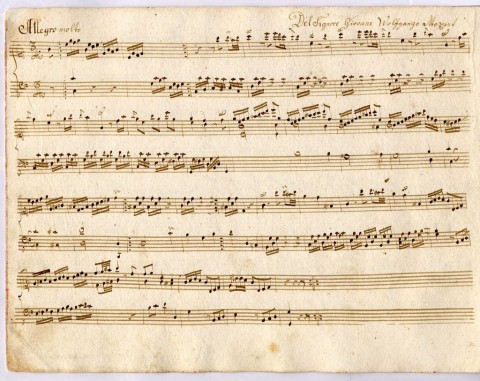

Combing through the dead man’s collection of old music manuscripts, Hildegard Herrmann-Schneider of the Institute for Tyrolean Music Research noticed a hand-written book with the date “1780” on the cover. On pages 12 to 14 she found an unidentified sonata movement with the tempo mark “allegro molto,” Italian for “very quickly.” On the upper right-hand side of page 12 was written “Del Signore Giovane Wolfgango Mozart,” or “The young Wolfgango Mozart.”

“Wolfgango” was a name Mozart’s father, Leopold, called him when he was a boy. Looking further into the manuscript, Herrmann-Schneider found several pieces that were already known to have been written by Leopold Mozart. Those compositions were respectfully marked “Signore Mozart,” or “Lord Mozart.”

Although the writing was clearly not in the hand of either the elder or the younger Mozart, the meticulousness of the transcriptions, along with the accuracy of every verifiable detail throughout the 160-page book, led Herrmann-Schneider to suspect that the composition by “The Young Wolfgango Mozart” was an authentic, previously unknown piece.

On the back of the manuscript was the copyist’s name: Johannes Reiserer. After an extensive investigation, Herrmann-Schneider was able to learn that Reiserer was born in 1765 and had gone to gymnasium, or high school, in Salzburg, where he was a member of the cathedral choir from 1778 to 1780. That would have placed him in close proximity to Leopold Mozart. “Researchers have thus concluded,” writes The History Blog, “that Johannes Reiserer used the notebook to copy compositions as part of a rigorous program of music instruction by Kapellhaus music masters, perhaps Leopold himself.”

Based on the style and the level of accomplishment in the piece, now known as the “Allegro Molto in C Major,” researchers place the date of composition at around 1767, when Mozart was 11 years old. A press release from the Institute for Tyrolean Music Research describes the piece:

Mozart frequently selected a C‑major key, and the Allegro molto has a sonata form with a length of 84 measures. Its ambitus is tailored to the clavichord. The Allegro molto could be a first major attempt by Wolfgang Amadé to assert himself in the area of the sonata form. This is suggested by the relatively high level of compositional technique.…Throughout the Allegro molto, thematic formation, compositional setting and harmony have a number of components that are found repeated in other Mozart piano works. Hardly a compositional detail points to a contradiction with the general characteristics of Mozart’s comsummate musical composition. According to current scholarly knowledge, it must therefore be regarded as an authentic sonata movement by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

Austrian musician Florian Birsak, who specializes in playing early keyboard instruments, gave the premier performance of the piece on Mozart’s own fortepiano last Friday at the Mozart family home in Salzburg, which is now a museum of the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation. You can watch a video, above, which was recorded sometime earlier in the same place and on the same instrument. You can also read a PDF of the score, and download Birsak’s recording at iTunes.

The first page of Mozart’s Allegro Molto in C Major (above) from the 1780 notebook. Credit: Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation.

via @MatthiasRascher

Star Gazing from the International Space Station (and Free Astronomy Courses Online)

Don Pettit joined NASA in 1996 and has since logged more than 176 days in space, living abord the International Space Station (ISS) multiple times, and always taking his camera with him. In the past, he has shown us What It Feels Like to Fly Over Planet Earth, Views of the Aurora Borealis Seen from Space, and How to Drink Coffee at Zero Gravity. Now we get an edited version of what it looks like to star gaze from low orbit. Whether you look up or down, you can’t lose.

Looking to dig a little deeper into what’s happening out there in the cosmos? Then you might want to spend some time with the courses listed in the Astronomy section of our Free Courses collection.

- Astrobiology and Space Exploration – iTunes – YouTube – Lynn Rotschild, Stanford

- Astronomy 101 – iTunes – Web Site – Scott Miller, Mercedes Richards & Stephen Redman, Penn State

- Exploring Black Holes: General Relativity & Astrophysics –YouTube – iTunes Video — Web Site – Edmund Bertschinger, MIT

- Frontiers and Controversies in Astrophysics - YouTube — iTunes Audio – iTunes Video – Download Course – Charles Bailyn, Yale

- Introduction to Astrophysics — iTunes — Joshua Bloom, UC Berkeley

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and now Google Plus and start sharing intelligent media with your friends! They’ll thank you for it.

Robert Frost Recites ‘Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening’

Today is the birthday of Robert Frost, who once said that a poem cannot be worried into being, but rather, “Like a piece of ice on a hot stove the poem must ride on its own melting.” Those words are from Frost’s 1939 essay, “The Figure a Poem Makes,” which includes the famous passage:

The figure a poem makes. It begins in delight and ends in wisdom. The figure is the same as for love. No one can really hold that the ecstasy should be static and stand still in one place. It begins in delight, it inclines to the impulse, it assumes direction with the first line laid down, it runs a course of lucky events, and ends in a clarification of life–not necessarily a great clarification, such as sects and cults are founded on, but in a momentary stay against confusion.

To celebrate the 138th anniversary of the poet’s birth, we bring you rare footage of Frost reciting his classic poem, “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening.” You can also listen to a four-part recording (below) of Frost reading a selection of his poems in 1956, courtesy of Harper Audio.

- Robert Frost Reading, Part One: “The Road Not Taken,” “The Pasture,” “Mowing,” “Birches,” “After Apple-Picking,” and “The Tuft of Flowers.”

- Robert Frost Reading, Part Two: “West-Running Brook” and “The Death of the Hired Man.”

- Robert Frost Reading, Part Three: “Mending Wall,” “One More Brevity,” “Departmental,” “A Considerable Speck,” and “Why Wait for Science.”

- Robert Frost Reading, Part Four: “Etherealizing,” “Provide, Provide,” “One Step Backward Taken,” “Choose Something Like a Star,” “Happiness Makes Up in Height,” and “Reluctance.”

The Animation of Billy Collins’ Poetry: Everyday Moments in Motion

The first time I saw Billy Collins speak, he appeared at my college convocation, toward the end of his years as United States Poet Laureate. Now, the second time I’ve seen Billy Collins speak, he appears giving this TEDTalk, “Everyday Moments, Caught in Time,” in which he makes fun of his own tendency to mention his years as United States Poet Laureate. But he mostly uses his fifteen minutes onstage in Long Beach in front of TED’s swooping cameras to talk about how the Sundance Channel animated five of his poems. A booster of poetry “off the shelf” and into public places — subways, billboards, cereal boxes — he figured that even such an “unnatural and unnecessary” merger could further the cause of eluding humanity’s “anti-poetry deflector shields that were installed in high school.”

Collins also notes that the idea for the project stirred the embers of his “cartoon junkie” childhood, when Bugs Bunny was his muse. Stylistically, however, the producers at the Sundance Channel kept quite far indeed from the Merrie Melodies. These animated poems opt instead for an aesthetic that takes pieces of visual reality and repurposes them in ways we don’t expect: look at the real arm slithering across the pages in the first poem, the tangible-looking dolls and doll environments of the second poem, or the drifting photographic cutouts of the third. Not to get too grand about it, but isn’t this what poetry itself is supposed to do? Don’t the words themselves also cut out fragments of actual existence and position them, recontextualize them, and move them around in ways that surprise us? The substance of these shorts — fountain pens, figurines, car keys, paper boats, matchsticks, mice — may seem like the last word in mundanity, but perceived through the differently “real” lenses of Collins’ poetry and this unusual animation, they inspire curiosity again.

Related content:

3 Year Old Recites Poem, “Litany” By Billy Collins

Bill Murray Reads Poetry At Construction Site

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Free Science Fiction Classics on the Web: Huxley, Orwell, Asimov, Gaiman & Beyond

Today we’re bringing you a roundup of some of the great Science Fiction, Fantasy and Dystopian classics available on the web. And what better way to get started than with Aldous Huxley reading a dramatized recording of his 1932 novel, Brave New World. The reading aired on the CBS Radio Workshop in 1956. You can listen to Part 1 here and Part 2 here.

(FYI: You can download Huxley’s original work — as opposed to the dramatized version — in audio by signing up for a Free Trial with Audible.com, and that applies to other books mentioned here as well.)

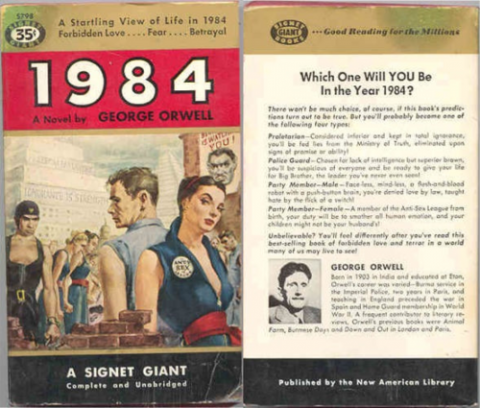

Little known fact. Aldous Huxley once gave George Orwell French lessons at Eton. And, 17 years after the release of Brave New World, Huxley’s pupil published 1984. The seminal dystopian work may be one of the most influential novels of the 20th century, and it’s almost certainly the most important political novel from that period. You can find it available on the web in three formats: Free eText — Free Audio Book – Free Movie.

In 1910, J. Searle Dawley wrote and directed Frankenstein. It took him three days to shoot the 12-minute film (when most films were actually shot in just one day). It marked the first time that Mary Shelley’s classic monster tale (text — audio) was ever adapted to film. And, somewhat notably, Thomas Edison had a hand (albeit it an indirect one) in making the film. The first Frankenstein film was shot at Edison Studios, the production company owned by the famous inventor.

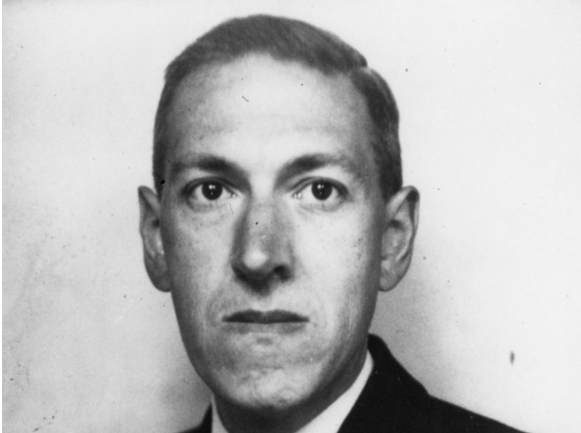

Stephen King and Joyce Carol Oates — they both pay homage to H.P. Lovecraft and his great tales. And you can too by spending time with his collected works, available in etext formats here and audio formats here (Free Mp3 Zip File – Free Stream).

Philip K. Dick published 44 novels and 121 stories during his short lifetime, solidifying his position as one of America’s top sci-fi writers. If you’re not intimately familiar with his novels, then you almost certainly know major films based on Dick’s work – Blade Runner, Total Recall, A Scanner Darkly and Minority Report. To get you acquainted with PKD’s writing, we have culled together 14 short stories for your enjoyment.

eTexts (find download instructions here)

- “Beyond the Door”

- “Beyond Lies the Wub”

- “Mr. Spaceship”

- “Piper in the Woods”

- “Second Variety”

- “The Crystal Crypt”

- “The Defenders”

- “The Eyes Have It”

- “The Gun”

- “The Hanging Stranger”

- “The Skull”

- “The Variable Man”

- “Tony and the Beetles”

- “We Can Remember It For You Wholesale”

- iPad/iPhone

Audio

- “Beyond Lies the Wub” – Free MP3

- “Beyond the Door” – Free MP3

- “Second Variety” – Free MP3 Zip File – Stream Online

- “The Defenders” — Free MP3

- “The Hanging Stranger” – Free MP3

- “The Variable Man” – Free MP3 Zip File – Stream Online

- “Tony and the Beetles” – MP3 Part 1 – MP3 Part II

Back in the late 1930s, Orson Welles launched The Mercury Theatre on the Air, a radio program dedicated to bringing dramatic, theatrical productions to the American airwaves. The show had a fairly short run, lasting from 1938 to 1941. But it made its mark. During these few years, The Mercury Theatre aired The War of the Worlds, an episode narrated by Welles that led many Americans to believe their country was under Martian attack. The legendary production, perhaps the most famous ever aired on American radio, was based on H.G. Wells’ early sci-fi novel, and you can listen to the broadcast right here.

Between 1951 and 1953, Isaac Asimov published three books that formed the now famous Foundation Trilogy. Many considered it a masterwork in science fiction, and that view became official doctrine in 1966 when the trilogy received a special Hugo Award for Best All-Time Series, notably beating out Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Eventually, the BBC decided to adapt Asimov’s trilogy to the radio, dramatizing the series in eight one-hour episodes that aired between May and June 1973. Thanks to The Internet Archive you can download the full program as a zip file, or stream it online:

Part 1 |MP3| Part 2 |MP3| Part 3 |MP3| Part 4 |MP3| Part 5 |MP3| Part 6 |MP3| Part 7 |MP3| Part 8 |MP3|

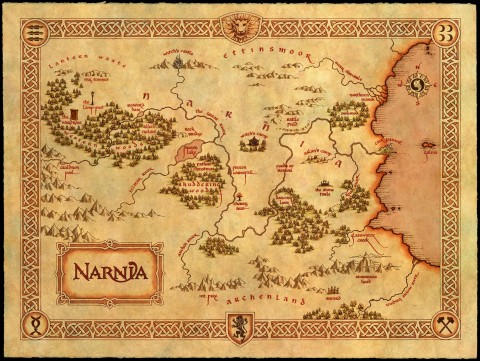

Before the days of Harry Potter, generations of young readers let their imaginations take flight with The Chronicles of Narnia, a series of seven fantasy novels written by C. S. Lewis. Like his friend J.R.R. Tolkien, Lewis served on the English faculty at Oxford University and took part in the Inklings, an Oxford literary group dedicated to fiction and fantasy. Published between 1950 and 1956, The Chronicles of Narnia has sold over 100 million copies in 47 languages, delighting younger and older readers worldwide.

Now, with the apparent blessing of the C.S. Lewis estate, the seven volume series is available in a free audio format. There are 101 audio recordings in total, each averaging 30 minutes and read by Chrissi Hart. Download the complete audio via the web or RSS Feed.

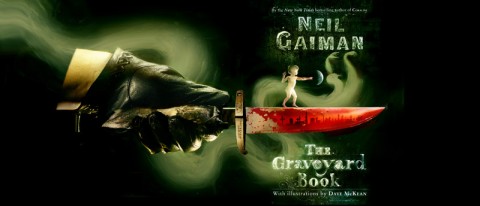

Neil Gaiman has emerged as one of today’s best fantasy writers. He has made comics respectable and published novels, including one that will be adapted by HBO. A great deal of his output, though, has been in the form of short stories, some available on the web in text format, others in audio.

Audio & Video

- “Harlequin Valentine” – Free Audio at Last.FM

- “How to Talk to Girls at Parties” – Free MP3

- “Orange” (read live) – Free Video

- “Other People” (read live) – Free Video

- The Truth Is a Cave in the Black Mountains – Free Audio

- The Graveyard Book (a novel read live with illustrations) – Free Video

- “Troll Bridge” (read live, starts at 4:00 mark) – Free iTunes

- “A Study in Emerald” – Free iTunes

Other Gaiman works can be download via Audible.com’s special Free Trial. More details here.

Text

- American Gods – Read the First Five Chapters Online

- “A Study in Emerald” — Read Online

- “Bitter Grounds” – Read Online

- “Cinnamon” – Read Online

- “Down to a Sunless Sea” – Read Online

- “I Cthulhu” – Read Online

- “The Case of the Four and Twenty Blackbirds” – Read Online

- “The Day the Saucers Came” – Read Online

- The Truth Is a Cave in the Black Mountains – Read Online

Between 1982 and 2000, Rudy Rucker wrote a series of four sci-fi novels that formed The Ware Tetralogy. The first two books in the series – Software and Wetware – won the Philip K. Dick Award for best novel. And William Gibson has called Rucker “a natural-born American street surrealist” or, more simply, one sui generis dude. And now the even better part: Rucker (who happens to be the great-great-great-grandson of Hegel) has released The Ware Tetralogy under a Creative Commons license, and you can download the full text for free in PDF and RTF formats. In total, the collection runs 800+ pages.

The Art and Science of Violin Making

Sam Zygmuntowicz is a world-renowned luthier, or maker of stringed instruments. Joshua Bell and Yo-Yo Ma play his instruments. In 2003, a violin he made for Isaac Stern sold at auction for $130,000–the highest price ever for an instrument by a living luthier. To sum up Zygmuntowicz’s stature as a builder of fine instruments, Tim J. Ingles, director of musical instruments for Sotheby’s, told Forbes magazine: “There are no more than six people who are at his level.”

Zygmuntowicz is the subject of a 2007 book by John Marchese called The Violin Maker: Finding a Centuries-Old Tradition in a Brooklyn Workshop. In one passage, Marchese writes about the mysterious acoustical qualities of the violin, which he likens to a magic box:

The laws that govern the building of this box were decided upon a short time before the laws of gravity were discovered, and they have remained remarkably unchanged since then. It is commonly thought that the violin is the most perfect acoustically of all musical instruments. It is quite uncommon to find someone who can explain exactly why. One physicist who spent decades trying to understand why the violin works so well said that it was the world’s most analyzed musical instrument–and the least understood.

The most famous, and fabled, stringed instruments are those that were made in Cremona, Italy, in the late 17th and early 18th centuries by Antonio Stradivari and a handful of other masters. In Zygmuntowicz’s workshop in the Park Slope neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York, there is a bumper sticker that says, “My other fiddle is a Strad.” Behind the joke lies a serious point. Zygmuntowicz wants great musicians to use his instruments–not because they are cheaper than a Stradivarius, but because they are better. He’s trying to break a barrier that has been firmly in place for centuries. “I call it the ‘Strad Ceiling,’ ” he told NPR in 2008. “You know, if someone has a Strad in their case, will they play your fiddle?”

Although Joshua Bell owns a Zygmuntowicz, he mostly calls on the luthier to make fine adjustments to his Stradivarius. But Eugene Drucker of the Emerson String Quartet told Forbes that he actually prefers his Zygmuntowicz to his 1686 Stradivarius in certain situations. “In a large space like Carnegie Hall,” he said, “the Zygmuntowicz is superior to my Strad. It has more power and punch.” In spite of the mystique that surrounds Stradivari and the other Cremona masters, Zygmuntowicz sees no reason why a modern luthier couldn’t make a better instrument. “There isn’t any ineffable essence,” he told the The New York Times earlier this year, “only a physical object that works better or worse in a variety of circumstances.”

For a quick introduction to Zygmuntowicz’s work, watch a new video, above, by photographer and filmmaker Dustin Cohen, and an earlier piece by Jon Groat of Newsweek, below. And to dive deeper into the science of the violin, be sure to visit the “Strad3D” Web site, which features fascinating excerpts from Eugene Schenkman’s film about Zygmuntowicz’s collaboration with physicist George Bissinger on a project using 3D laser scans, CT scans and other technologies to analyze the acoustical properties of violins by Stradivari and Giuseppe Guarneri. As Zygmuntowicz told Strings magazine in 2006, “What makes those violins work is more knowable now than it ever was.” H/T Kottke

Note: if you have any problems watching the video below, you can watch an alternate version here.

Tom Schiller’s 1975 Journey Through Henry Miller’s Bathroom (NSFW)

No surprise, you might think, that a documentary about the man who wrote Tropic of Cancer would merit an NSFW label. But what if I were to tell you that this particular documentary spends almost every one of its 35 minutes in Henry Miller’s bathroom? Yet the writer has imbued this bathroom with a great deal of notoriety, at least in his circles, thanks to how carefully he adorned its walls with visual curiosities. Following its subject as he grunts himself awake, puts on a robe, and tells the stories behind whatever the camera sees, Henry Miller Asleep and Awake uses these bathroom walls as a gateway into his mind. We see reproductions of paintings by Hieronymus Bosch and Paul Gauguin. We see portraits of Miller’s personally inspiring luminaries, like Hermann Hesse and the lesser-known Swiss modernist novelist Blaise Cendrars. And of course, we see a still from the Tropic of Cancer movie and the expected amount of nude pin-ups. “I put these here expressly for the people who want to be shocked,” Miller explains.

Tom Schiller, the documentary’s director, made his name creating short films for Saturday Night Live. Obscurity-oriented cinephiles may know him best as the director of Nothing Lasts Forever, a 1984 comedy featuring Bill Murray and Dan Aykroyd that, to this day, languishes somewhere in Warner Brothers’ legal department. Schiller received this guided tour of Miller’s bathroom — and, by extension, his memory — in 1975, when the author had reached his 82nd year and fifth marriage; his wife, Hiroko “Hoki” Tokuda, appears in one of the wall’s photographs. He also points out a blown-up cover of a favorite Junichiro Tanizaki novel, a scrap of Chinese text for which every Chinese visitor has a completely different translation, an image of a legendarily randy Buddhist monk, dramatic portraits of Chinese actresses and Japanese bar girls, and — in the absence of religious iconography of any other kind — countless representations of the Buddha. And if you’d like to see something else from Asia presented in an especially Milleresque spirit, don’t miss when Schiller’s camera turns toward the shower. Just make sure you’re not watching at work. Seriously.

The films has been added to our big collection of Free Movies Online. Look under Documentary.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Filmmaker James Cameron Going 36,000 Feet Under the Sea

This week, filmmaker James Cameron (Titanic, Avatar, The Abyss) hopes to go where only two men have gone before, diving 36,000 feet beneath the sea, to the Mariana Trench, the deepest known place on Earth. It’s basically Mount Everest in the inverse. Cameron plans to make the historic solo journey in The Deepsea Challenger, a 24-foot-long vertical torpedo, built secretly in Australia over the last year eight years. (More on that here.) And when he reaches his destination, he’ll spend six hours shooting 3‑D video of the trench and collecting rocks and rare sea creatures with a robotic arm. Or so that’s the plan.

Above, James Cameron describes his mission in a National Geographic video. Below, you’ll find an animation of the Mariana Trench dive created by The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). You can track Cameron’s voyage on the NatGeo website and find a detailed description of the actual dive right here.

Terry Gilliam’s Debut Animated Film, Storytime

Terry Gilliam’s funny debut film, Storytime, features three early examples of the Monty Python animator’s twisted take on life. The film is usually dated 1968, but according to some sources it was actually put together several years later. The closing segment, “A Christmas Card,” was created in late 1968 for a special Christmas-day broadcast of the children’s program Do Not Adjust Your Set, but the other two segments– “Don the Cockroach” and “The Albert Einstein Story”–were broadcast on the 1971–1972 British and American program The Marty Feldman Comedy Machine, which featured Gilliam’s Pythonesque animation sequences at the beginning and end of each show. Whatever the date of production, Storytime (now added to our collection of 675 Free Movies Online in the Animation Section) is an engaging stream-of-consciousness journey through Gilliam’s delightfully absurd imagination. If you’re a Terry Gilliam fan, don’t miss these other related items:

Terry Gilliam Shows You How to Make Your Own Cutout Animation

Terry Gilliam: The Difference Between Kubrick (Great Filmmaker) and Spielberg (Less So)

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Cinema History by Titles & Numbers

Between the simple card opening D.W. Griffith’s 1916 Intolerance to the vibrating neon first onslaught of Gaspar Noé’s 2009 Enter the Void, Ian Albinson’s A Brief History of Title Design packs in countless iconic, representative, and otherwise fascinating examples of words that precede movies. As Editor-in-Chief of the blog Art of the Title, Albinson distinguishes himself as just the person you’d want to cut together a video like this. His selections move through the twentieth century from The Phantom of the Opera, King Kong, and Citizen Kane, whose stark stateliness now brings to mind the very architecture of the old movie palaces where they debuted, to the deliberate, textural physicality of The Treasure of Sierra Madre and Lady in the Lake. Then comes the late-fifties/early-sixties modernist cool of The Man With the Golden Arm and Dr. No, followed by Dr. Strangelove and Bullitt, both of which showcase the work of Pablo Ferro — a living chapter of title design history in his own right. After the bold introductions to the blockbusters of the seventies and eighties — Star Wars, Saturday Night Fever, Alien, The Terminator — but before the freshly extravagant design work of the current century, we find a few intriguingly marginal films of the nineties. How many regular cinephiles retain fond memories of Freaked, Mimic, and The Island of Dr. Moreau I don’t know, but clearly those pictures sit near and dear to the hearts of title enthusiasts.

An elaborate work of motion graphics in its own right, Evan Seitz’s 123Films takes the titles of fourteen films — not their title sequences, but their actual titles — and animates them in numerical order. If that doesn’t make sense, spend thirty seconds watching it, and make sure you’re listening. Doesn’t that calmly malevolent computer voice sound familiar? Does the color scheme of that “4” look familiar, especially if you read a lot of comic books as a kid? And certainly you’ll remember which of the senses it takes to see dead people. This video comes as the follow-up to Seitz’s ABCinema, a similar movie guessing game previously featured on Open Culture. Where that one got you thinking about film alphabetically, this one will get you thinking about it numerically.

Related Content:

A Brief Visual Introduction to Saul Bass’ Celebrated Title Designs

450 Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, etc.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.