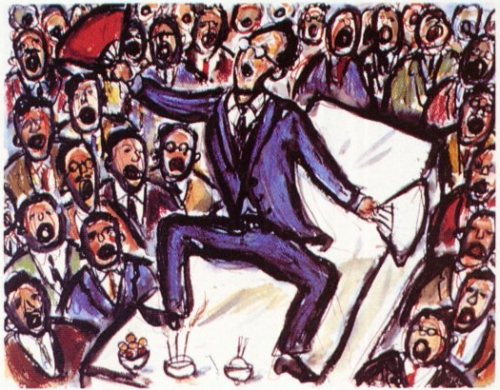

Founded and directed by physicist Lawrence Krauss, Arizona State’s Origins Project has for several years brought together some of the biggest minds in the sciences and humanities for friendly debates and conversations about “the 21st Century’s greatest challenges.” Previous all-star panels have included Krauss, Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Bill Nye, Brian Greene, and Richard Dawkins. Stephen Hawking has graced the ASU Origins Project stage, as has actor and science communicator Alan Alda. And this past March, in a sold-out, highly-anticipated Origins Project event, Krauss welcomed Noam Chomsky to the stage for a lengthy interview, which you can watch above.

Although Krauss says he’s wary of hero worship in his laudatory introduction, he nonetheless finds himself asking “What Would Noam Chomsky Do” when faced with a dilemma. He also points out that Chomsky has been “marginalized in U.S. media” for his anti-war, anarchist political views. Those views, of course, come widely into play during the conversation, which ranges from the theory and purpose of education—a subject Chomsky has expounded on a great deal in books and interviews—to the fate of political dissidents throughout history.

Chomsky also gives us his views on science and technology, particularly in the Q&A portion of the talk above, in which he answers questions about artificial intelligence—another subject he’s touched on in the past—and animal experimentation, among a great many other topics. Krauss mostly hangs back during the initial discussion but takes a more active role in the session above, offering views on medical and scientific ethics that will be familiar to those who follow his atheist activism and championing of rationality over religious dogma.

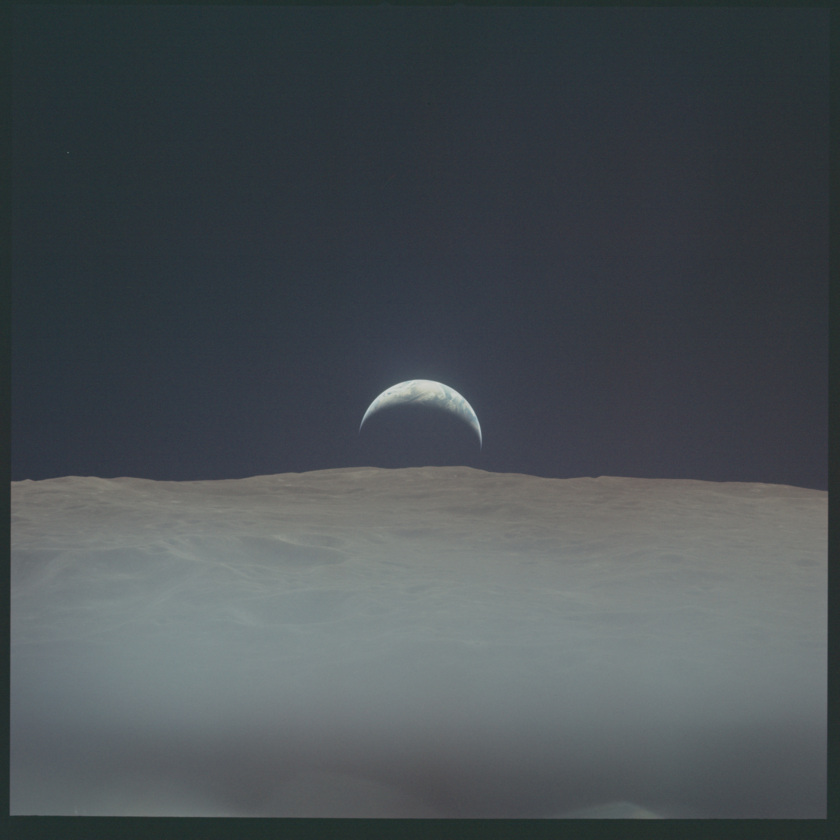

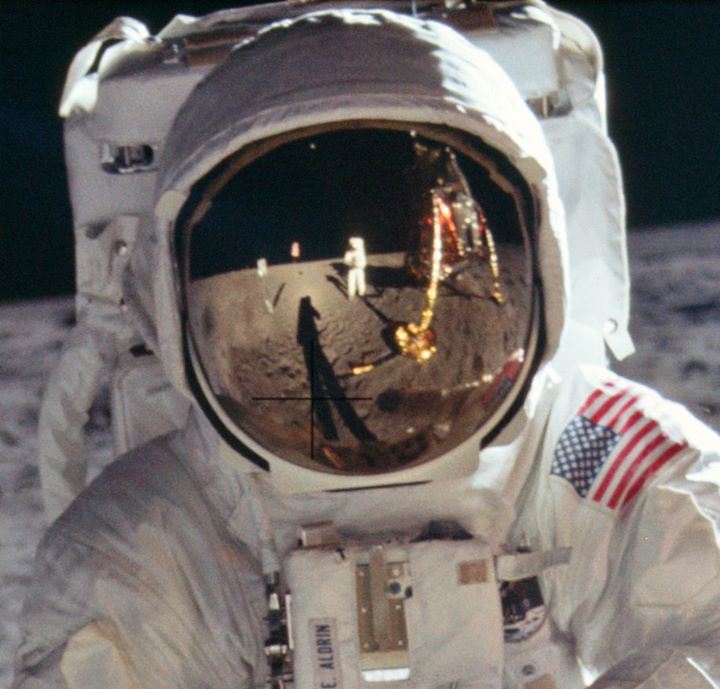

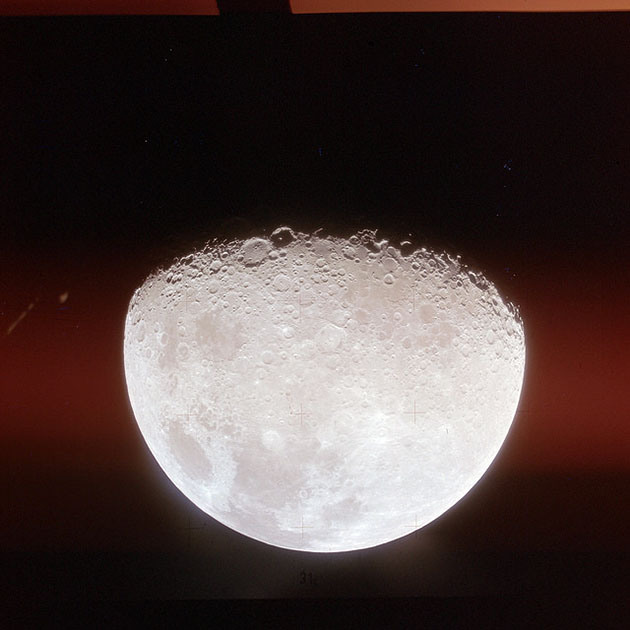

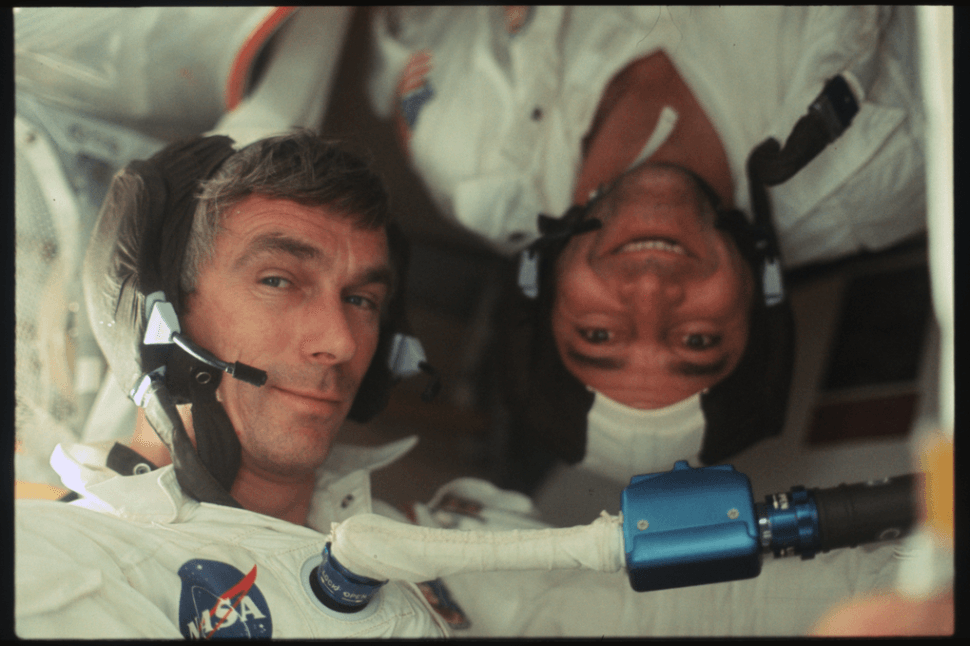

What you won’t see in the video above is a conversation Chomsky and Krauss had with Motherboard’s Daniel Oberhaus, who caught up with both thinkers during the ASU event to get their take on what he calls “another great space race.” As Oberhaus makes clear, the current competition is not necessarily between global superpowers, but—as with so much modern research and development—between public and private entities, such as NASA and Space X. As we briefly discussed in a post yesterday on the huge amount of public domain space photography freely available for use, private space exploration makes research proprietary, mitigating the potential public benefits of government programs.

As Chomsky puts it, “the environment, the commons… they’re a common possession, but space is even more so. For individuals to allow institutions like corporations to have any control over it is devastating in its consequences. It will also almost certainly undermine serious research.” He refers to the example of most modern computing—developed under publicly-funded government programs, then marketed and sold back to us by corporations. Krauss makes a case for unmanned space exploration as the cost-effective option, and both thinkers discuss the problem of militarizing space, the ultimate goal of Cold War space programs before the fall of the Soviet Union. The conversation is rich and revealing and makes an excellent supplement to the already rich discussion Krauss and Chomsky have in the videos above.

Related Content:

Noam Chomsky Spells Out the Purpose of Education

Noam Chomsky Explains Where Artificial Intelligence Went Wrong

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness