Of all American poets, almost no one looms larger than Walt Whitman. As I once heard an old poet acquaintance say, American poets don’t need Shakespeare and the Bible; we’ve got Dickinson and Whitman. Indeed, Whitman’s voice emerges from the past like some American Moses, showing the way forward, opening his arms to hold his fractious countrymen together. One can bloviate all day about Walt Whitman. He tends to have that effect. But even Whitman, he of the serpentine lines full of the cargo of the continent, stretching from left margin to right, ocean to ocean, could be relatively succinct, and even about his favorite subject, America. Take his poem “America” from 1888:

Centre of equal daughters, equal sons,

All, all alike endear’d, grown, ungrown, young or old,

Strong, ample, fair, enduring, capable, rich,

Perennial with the Earth, with Freedom, Law and Love,

A grand, sane, towering, seated Mother,

Chair’d in the adamant of Time.

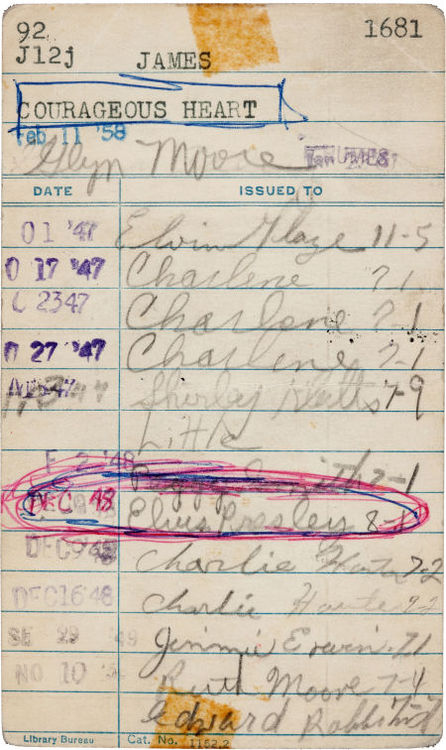

Now, believe it or not, you can hear what may well be the voice of Walt Whitman, American Moses, emerging from the past to read the first four lines of “America,” from a wax cylinder recording above. Most likely captured in 1889 or 1890 by Thomas Edison, this reading was originally found on a cassette called “The Voice of the Poets,” discovered in a library by Whitman scholar Larry Don Griffin. The cassette, made in 1974 and including the voices of Edna St. Vincent Millay and William Carlos Williams, takes the Whitman audio from a 1951 NBC radio program, whose announcer, Leon Pearson, claims comes from a wax cylinder recording made in 1890.

Surprisingly, the ’74 cassette tape, which landed in libraries across the country, seemed to go unnoticed by scholars until Griffin mentioned it in the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review in 1992. This mention sparked debate about the authenticity of the recording, and once scholarly debate is sparked, the fire can burn for decades, whole careers built on its embers. In this case, some scholars, including historian Allen Koenigsberg, argued that since no original wax cylinder has appeared, and mention of the recording in Edison’s correspondence is inconclusive, the provenance is suspect. Furthermore, Koenigsberg argued, the recording quality seems too good for the period. His conclusion comes backed by the analysis of audio experts. According to The Edisonian, a Rutger’s University Edison newsletter:

Analysts for both the Library of Congress and the Rodgers and Hammerstein Archives consulted on the case and agreed that the clarity of the recording was beyond what could be achieved in 1889 or 1890… the sound analysis along with the documentation difficulties led Koeningsberg to conclude that “the supposed Whitman recording is a fascinating fake.”

On the other side of this debate is the editor of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review, Ed Folsom, who presents his case in an article simply titled “The Whitman Recording,” in which he discusses problems with the Library of Congress analysis. Yet another partisan for authenticity, William Grimes—who covered the controversy for The New York Times points out that the voice sounds like what Whitman’s would have, and he makes a compelling argument that the poem would not at all be the obvious choice for a fake. Grimes cites unnamed “specialists in the history of the phonograph,” whom, he writes, “agree… that the possibility of outright fraud or a hoax is unlikely.”

And on it goes. No one can definitively settle the case, unless new evidence should come to light. With no intention of maligning Ed Folsom’s good faith, I can imagine the Whitman Quarterly editor wanting this to be true more than historian Koenigsberg and the LOC analysts. But I also want it to be Whitman, and so I’m glad to make an exuberant leap of American faith and think it’s him. From Edison wax cylinder recording, to radio broadcast, to cassette, to mp3, over more than a century of American poetry—it would be a perfectly Whitmanesque journey.

via @stevesilberman

Related Content:

Voices from the 19th Century: Tennyson, Gladstone, Whitman & Tchaikovsky

Thomas Edison Recites “Mary Had a Little Lamb” in Early Voice Recording

Mark Twain Captured on Film by Thomas Edison in 1909.

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness