“Civilization begins with distillation,” William Faulkner once said, and like many of the great writers of the 20th century — Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, James Joyce — the bard of Oxford, Mississippi certainly had a fondness for alcohol.

Unlike many of the others, though, Faulkner liked to drink while he was writing. In 1937 his French translator, Maurice Edgar Coindreau, was trying to decipher one of Faulkner’s idiosyncratically baroque sentences. He showed the passage to the writer, who puzzled over it for a moment and then broke out laughing. “I have absolutely no idea of what I meant,” Faulkner told Coindreau. “You see, I usually write at night. I always keep my whiskey within reach; so many ideas that I can’t remember in the morning pop into my head.”

Every now and then Faulkner would embark on a drunken binge. His publisher, Bennett Cerf, recalled:

The maddening thing about Bill Faulkner was that he’d go off on one of those benders, which were sometimes deliberate, and when he came out of it, he’d come walking into the office clear-eyed, ready for action, as though he hadn’t had a drink in six months. But during those bouts he didn’t know what he was doing. He was helpless. His capacity wasn’t very great; it didn’t take too much to send him off. Occasionally, at a good dinner, with the fine wines and brandy he loved, he would miscalculate. Other times I think he pretended to be drunk to avoid doing something he didn’t want to do.

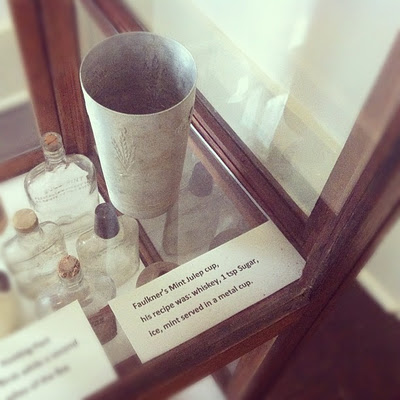

Wine and brandy were not Faulkner’s favorite spirits. He loved whiskey. His favorite cocktail was the mint julep. Faulkner would make one by mixing whiskey–preferably bourbon–with one teaspoon of sugar, a sprig or two of crushed mint, and ice. He liked to drink his mint julep in a frosty metal cup. (See image above.) The word “julep” first appeared in the late 14th century to describe a syrupy drink used to wash down medicine. Faulkner believed in the medicinal efficacy of alcohol. Lillian Ross once visited the author when he was ailing, and quoted him as saying, “Isn’t anythin’ Ah got whiskey won’t cure.”

On a cold winter night, Faulkner’s medicine of choice was the hot toddy. His niece, Dean Faulkner Wells, described the recipe and ritual for hot toddies favored by her uncle (whom she called “Pappy”) in The Great American Writers’ Cookbook, quoted last week by Maud Newton:

Pappy alone decided when a Hot Toddy was needed, and he administered it to his patient with the best bedside manner of a country doctor.

He prepared it in the kitchen in the following way: Take one heavy glass tumbler. Fill approximately half full with Heaven Hill bourbon (the Jack Daniel’s was reserved for Pappy’s ailments). Add one tablespoon of sugar. Squeeze 1/2 lemon and drop into glass. Stir until sugar dissolves. Fill glass with boiling water. Serve with potholder to protect patient’s hands from the hot glass.

Pappy always made a small ceremony out of serving his Hot Toddy, bringing it upstairs on a silver tray and admonishing his patient to drink it quickly, before it cooled off. It never failed.

Related Content:

William Faulkner Audio Archive Goes Online

William Faulkner Reads from As I Lay Dying