It is closing-time in the gardens of the West and from now on an artist will be judged only by the resonance of his solitude or the quality of his despair –Cyril Connolly

My mind has been drawn to lately Albert Camus’ The Stranger, in which an alienated French-Algerian man, simply called Meursault, shoots a nameless “Arab,” for no particular reason that he can divine. He thinks, perhaps, it may have been the sun in his eyes. Meursault is not a police officer, he has not been called to a scene. He ambles into a scene, sees a stranger coming toward him, and fires five shots, commenting—in language that recalls the impersonal copspeak of a “discharged weapon”—that “the trigger gave.”

The import of Camus’ 1942 novel—translated as The Outsider in the first British edition, with its introduction by despairing literary critic Cyril Connolly—became such a hobby horse for critics that Louis Hudon wrote in 1960, “L’Etranger no longer exists…. Almost everyone has approached Camus and L’Etranger bound by his own tradition, prejudices, or critical apparatus.” But maybe we cannot do otherwise. Maybe there is never the “magnificently naked purity of the text” Hudon eulogizes.

Part of the difficulty, Hudon alleged, was down to Camus himself, who made available his journals and manuscripts, thus encouraging over-interpretation. In 1955, Camus remarked, “I summarized The Stranger a long time ago, with a remark I admit was highly paradoxical: ‘In our society any man who does not weep at his mother’s funeral runs the risk of being sentenced to death.’” The book has been read and taught in light of this general statement ever since.

Recent commentary on The Stranger in English has turned, almost obsessively, on the translation of the novel’s first sentence: Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Typically, as in that first British edition, the line has been rendered “Mother died today”—using a “static, archetypal term… like calling the family dog ‘Dog’ or a husband ‘Husband,’” writes Ryan Bloom in The New Yorker. For decades, Anglophone readers have come to know Meursault “through the detached formality of his statement.”

Perhaps if translators were to leave the word in its original French—maman—which connotes something between the formal “Mother” and childish “Mommy”—we would see Meursault differently. (French-speaking readers, of course, are not faced with this particular interpretive challenge.) But whether or not it makes a difference, and no matter how we have imagined Meursault’s internal voice, we can hear it the way Camus heard it, in the audio above from 1947, in which the author reads the opening section of the novel in French. (See the French passage and English translation at the bottom of the post.)

Does it matter whether we translate maman as “Mother” or leave it be? “Mommy” may be inappropriate, and while “mom” might “seem the closest fit… there’s still something off-putting and abrupt about the single-syllable word.” (Some translations have opted for the equally jarring, one-syllable “Ma.”) If the debate seems agonizingly scholastic, keep in mind that Meursault’s fate, his very life, as Camus remarked, turns on whether a jury views him as a sympathetic fellow human or a psychopath, based on exactly this kind of scrutiny.

But what of the murder? The murder victim? A man who is given no name, no history, no family, and no funeral that we see. Leaving maman in French, writes Bloom, serves another purpose—reminding readers “that they are in fact entering a world different from their own”—that of Camus’ native colonial French Algeria. (Though in some ways not so different.) Here, “the likelihood of a Frenchman in colonial Algeria getting the death penalty for killing an armed Arab was slim to nonexistent.” This historical context is often elided.

Many of us were taught that the murder is all of a piece with Meursault’s callous detachment from the world. But that interpretation itself betrays a profound callousness, one that takes for granted Meursault’s objectification of the faceless “Arab.” Absent in such a reading is the fact that Meursault is “a citizen of France domiciled in North Africa,” as Connolly writes, “an homme du midi yet one who hardly partakes of the traditional Mediterranean culture” …a colonist, who, because of his race and nationality, has likely been taught to view the Algerian “Arabs” as sub-human, other, outside, strange, undifferentiated, an enemy….

The shooting is a reflex born of that training. Why does he do it? He doesn’t know.

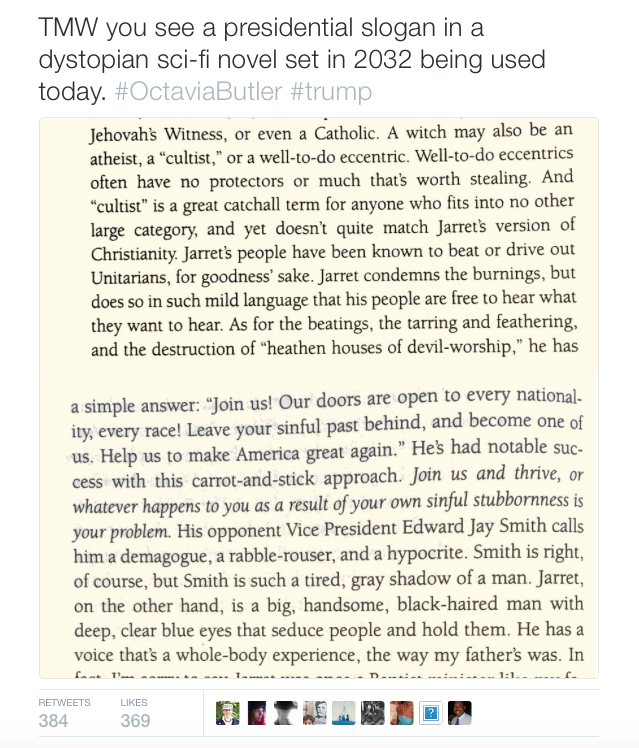

The freshest response to Camus’ novel happens to be a novel itself, Algerian writer Kamel Daoud’s 2013 The Meursault Investigation, narrated by “the Arab”’s younger brother, Harun, who notes that in Camus’ book “the world ‘Arab’ appears twenty-five times, but not a single name, not once.” Here, writes Claire Messud in her review, “Harun wants his listener to understand that the dead man had a name [“Musa”] and a family.” In his metafictional commentary, Harun ruminates: “Just think, we’re talking about one of the most read books in the world. My brother might have been famous if your author had merely deigned to give him a name.”

Daoud’s novel does not exist to upbraid Camus or supplant The Stranger but to humanize the figure of “the Arab,” tell the complicated stories of Algerian identity, and ask some very Camus-inspired questions about the morality of killing. Perhaps, as the consideration of maman suggests to us English readers, Meursault is not a sociopath, or an emotional vacuum, or a symbol of the amoral absurd, but a person who had a certain vague fondness for his mother, just not in the falsely sentimental way his judges would like. This is what we often take away from the novel—Meursault’s condemnation of a social order that insists on an inauthentic performance of humanity. Perhaps also Meursault’s seemingly senseless, casual murder of “the Arab” is not an outcome of his existential emptiness but a reflexively ordinary act that makes him more like his peers than we would like to admit.

Here’s the full text, in French and English, that Camus reads:

Aujourd’hui, maman est morte. Ou peut-être hier, je ne sais pas. J’ai reçu un télégramme de l’asile : « Mère décédée. Enterrement demain. Sentiments distingués. » Cela ne veut rien dire. C’était peut-être hier. (See full text below)

L’asile de vieillards est à Marengo, à quatre-vingts kilomètres d’Alger. Je prendrai l’autobus à deux heures et j’arriverai dans l’après-midi. Ainsi, je pourrai veiller et je rentrerai demain soir. J’ai demandé deux jours de congé à mon patron et il ne pouvait pas me les refuser avec une excuse pareille. Mais il n’avait pas l’air content. Je lui ai même dit : « Ce n’est pas de ma faute. » Il n’a pas répondu. J’ai pensé alors que je n’aurais pas dû lui dire cela. En somme, je n’avais pas à m’excuser. C’était plutôt à lui de me présenter ses condoléances. Mais il le fera sans doute après-demain, quand il me verra en deuil. Pour le moment, c’est un peu comme si maman n’était pas morte. Après l’enterrement, au contraire, ce sera une affaire classée et tout aura revêtu une allure plus officielle.

J’ai pris l’autobus à deux heures. Il faisait très chaud. J’ai mangé au restaurant, chez Céleste, comme d’habitude. Ils avaient tous beaucoup de peine pour moi et Céleste m’a dit : « On n’a qu’une mère. » Quand je suis parti, ils m’ont accompagné à la porte. J’étais un peu étourdi parce qu’il a fallu que je monte chez Emmanuel pour lui emprunter une cravate noire et un brassard. Il a perdu son oncle, il y a quelques mois.

J’ai couru pour ne pas manquer le départ. Cette hâte, cette course, c’est à cause de tout cela sans doute, ajouté aux cahots, à l’odeur d’essence, à la réverbération de la route et du ciel, que je me suis assoupi. J’ai dormi pendant presque tout le trajet. Et – 5 – quand je me suis réveillé, j’étais tassé contre un militaire qui m’a souri et qui m’a demandé si je venais de loin. J’ai dit « oui » pour n’avoir plus à parler.

MOTHER died today. Or, maybe, yesterday; I can’t be sure. The telegram from the Home says: YOUR MOTHER PASSED AWAY. FUNERAL TOMORROW. DEEP SYMPATHY. Which leaves the matter doubtful; it could have been yesterday.

The Home for Aged Persons is at Marengo, some fifty miles from Algiers. With the two o’clock bus I should get there well before nightfall. Then I can spend the night there, keeping the usual vigil beside the body, and be back here by tomorrow evening. I have fixed up with my employer for two days’ leave; obviously, under the circumstances, he couldn’t refuse. Still, I had an idea he looked annoyed, and I said, without thinking: “Sorry, sir, but it’s not my fault, you know.”

Afterwards it struck me I needn’t have said that. I had no reason to excuse myself; it was up to him to express his sympathy and so forth. Probably he will do so the day after tomorrow, when he sees me in black. For the present, it’s almost as if Mother weren’t really dead. The funeral will bring it home to me, put an official seal on it, so to speak. …

I took the two‑o’clock bus. It was a blazing hot afternoon. I’d lunched, as usual, at Céleste’s restaurant. Everyone was most kind, and Céleste said to me, “There’s no one like a mother.” When I left they came with me to the door. It was something of a rush, getting away, as at the last moment I had to call in at Emmanuel’s place to borrow his black tie and mourning band. He lost his uncle a few months ago.

I had to run to catch the bus. I suppose it was my hurrying like that, what with the glare off the road and from the sky, the reek of gasoline, and the jolts, that made me feel so drowsy. Anyhow, I slept most of the way. When I woke I was leaning against a soldier; he grinned and asked me if I’d come from a long way off, and I just nodded, to cut things short. I wasn’t in a mood for talking.

Related Content:

Albert Camus’ Historic Lecture, “The Human Crisis,” Performed by Actor Viggo Mortensen

Albert Camus: The Madness of Sincerity — 1997 Documentary Revisits the Philosopher’s Life & Work

Albert Camus Wins the Nobel Prize & Sends a Letter of Gratitude to His Elementary School Teacher (1957)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness