On the 750th birthday of Dante Alighieri—composer of the dizzyingly epic medieval poem the Divine Comedy—English professor John Kleiner pointed to one way of helping undergraduate students understand the Italian poet’s importance: an “obvious comparison” with Shakespeare. They both occupy singularly definitive places in their respective languages and literatures as well as in world literature, Kleiner suggested, and indeed no less a critical personage than T.S. Eliot once wrote, “Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third.”

And yet, those who know the epic English poems Paradise Lost and Paradise Regained—heavily influenced by Dante’s work—may find John Milton a more apt comparison. Milton also made complex uses of theology as political allegory, and wrote political tracts as passionate and resolute as his poetry. Both Milton and Dante were intensely partisan writers who expanded their worldly conflicts into the eternal realms of heaven and hell.

Like Milton, Dante’s formative political experience involved a civil war—in his case between two factions known as the Guelphs and the Ghibellines (then further between the “White Guelphs” and the “Black Guelphs.”) And like Milton, Dante had special access to the powerful of his day. Unlike the English poet and defender of regicide, however, Dante was a strict monarchist who even went so far as to propose a global monarchy under Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII. And while Milton veiled his political references in allegorical symbolism, Dante boldly named his adversaries in his poem, and subjected them to grisly, inventive tortures in his vivid depiction of hell.

Indeed, Dante’s literary persecution of his opponents presents one of the foremost difficulties for modern readers of the Inferno. In addition to cataloguing the number of classical and mythological characters Dante encounters in his infernal sojourn, we must wade through pages of contextual notes to find out who various contemporary characters were, and why they have been condemned to their respective levels and torments. Most of his named historical sufferers—including Pope Boniface VII—had died by the time of his writing, but some still lived. Of two such cases, one online guide notes humorously, “Dante explains their presence in Hell by saying that they were so sinful that the devil did not wait for them to die before snatching their souls…. Obviously libel laws were not that strict in Medieval Italy.”

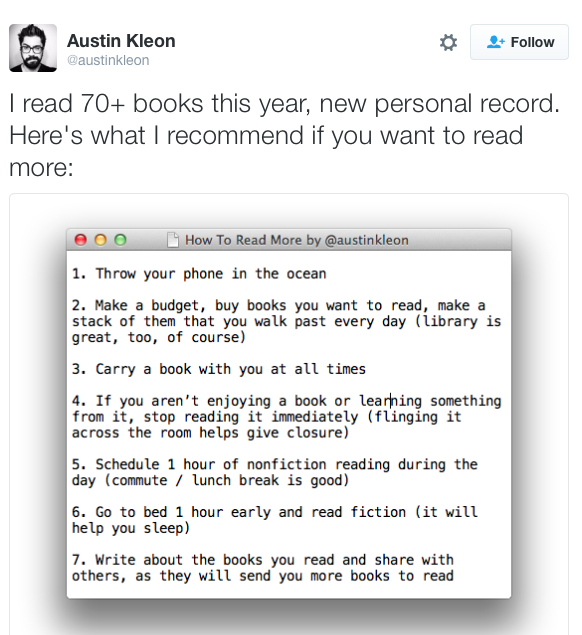

The Inferno treats the existence of hell and the grievous sins that consign its inhabitants there with the utmost seriousness. And yet, the presence of Dante’s many personal and political enemies injects no small amount of dark humor into the poem, such that one can read it as political satire as well as an ingenious marriage of medieval Catholic theology and philosophy with the poetry of courtly love. The richness of the Divine Comedy’s rhetorical world invites a great many interpretations, but it also demands much of its reader. To meet its challenge, we might lean on excellent reference guides like the online World of Dante, which offers a fully annotated text in English and Italian, as well as maps, charts, and diagrams of the hellish world, and visual interpretations like Gustave Doré’s illustration from Canto 6 at the top.

And we might listen to the poem read aloud. Here, we have one reading of Cantos I‑VIII of the Inferno by poet John Ciardi, from his translation of the poem for a Signet Classics Edition. Ciardi (known as “Mr. Poet” during his day) made his recording in 1954 for Smithsonian Folkways records, and the liner notes of the LP, which you can download here, contain the excerpted “verse rendering for the modern reader.” The translation preserves Dante’s terza rima in very eloquent, yet accessible language, fitting given Dante’s own use and defense of the vernacular. You can hear the complete reading on Spotify (download the software here) or on Youtube just above.

Ciardi’s reading will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

You can also find a course on Dante (from Yale) in our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

Mœbius Illustrates Dante’s Paradiso

William Blake’s Last Work: Illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy (1827)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness