In 1971, Abbie Hoffman published his countercultural how-to/”hip Boy Scout handbook,” Steal This Book. Since then, millions of people have queued up to pay for it. Did they misread the very clear instruction in the title? Or did most of Hoffman’s readers think of it as another Yippie hoax, not to be taken any more seriously than Pigasus, the 145-pound pig Hoffman and his merry band of pranksters nominated for president in 1968? Seems to me Hoffman was dead serious about the pig, and about his call for shoplifting, or “inventory shrink.”

Nevertheless, millions of people have needed no unambiguous prodding from the Andy Kaufman of political theater to steal millions of other books from shops worldwide, to the detriment of publishers and booksellers and the edification of penurious readers. The books most stolen from bookstores happen to also be those that might best appeal to the kind of radical anarcho-hippies Hoffman addressed, including Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and anything by Bukowski and Burroughs.

Also high on the list is Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, not a novel we necessarily associate with dumpster-divers and boxcar-hoppers, but one of many Murakamis book thieves have taken to lifting nonetheless. Kurt Vonnegut ranks highly, including his very popular Cat’s Cradle and Breakfast of Champions. Other favorite authors include hyper-masculine seers of societal decadence, Chuck Palahniuk and Brett Easton Ellis.

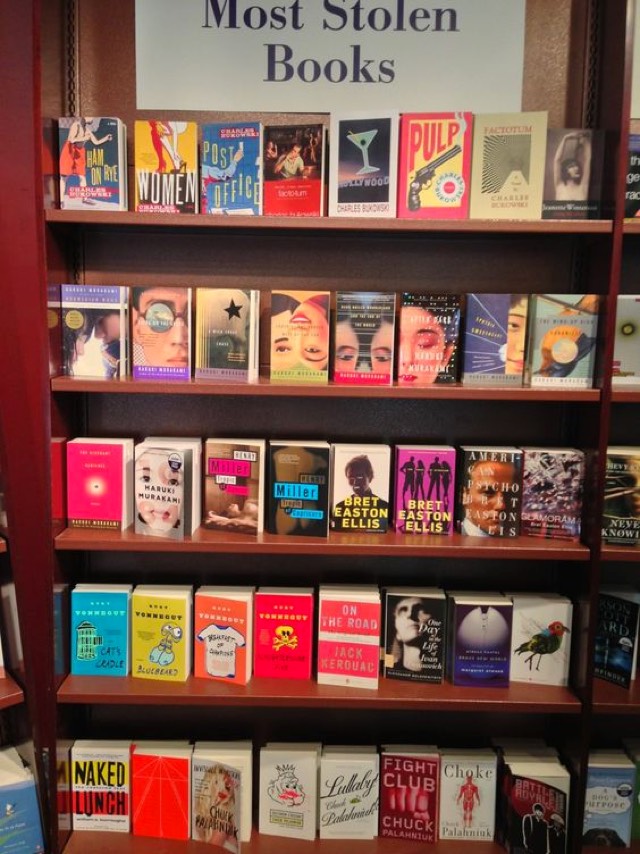

How do we know this? One source is simply an image, above, tweeted out by Vintage/Anchor Books—a photo of a “Most Stolen Books” shelf at an unnamed bookstore. We might assume whichever store it is has all the evidence it needs from a consistently shrinking inventory of these titles. And another major bookstore confirms much of the anonymous shelf above.

Melissa MacAulay at The Editing Company blog writes that during a part-time gig at Canadian giant Indigo books, Palahniuk’s Fight Club ended up behind the counter. Readers looking for a copy instead found “a small sign directing you to ‘please ask for assistance.’” In addition to Palahniuk, Indigo’s big three most stolen authors are Murakami, Kurt Vonnegut, and Bukowski, who tops out as the “reigning king of ‘Shoplift Lit.’”

In yet another “Most Stolen” list, blogger Candice Huber—inspired by Markus Zusak’s 2013 novel The Book Thief—undertook her own informal research and came up with similar results, with Bukowski and Burroughs in the top spot and Kerouac at number two. “All of the books listed,” notes Kottke, “are by men and most by ‘manly’ men” (whatever that means). See her list, with commentary, below.

Anything by Charles Bukowski or William S. Burroughs. Book sellers tend to keep books by these authors behind the counter because they get swiped so often.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac. If you notice a theme here, Bukowski, Burroughs, and Kerouac books all share, shall I put it bluntly, content of sex and drugs. It seems that those most likely to commit a reckless act (stealing) are also interested in reading about reckless acts.

Graphic Novels. The majority of book thieves are young, white males, and this is what they read.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Which was actually one of the most commonly stolen books long before the movie came out.

Various Selections from Ernest Hemingway, including A Moveable Feast and The Sun Also Rises.

Naked and Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris. David Sedaris? Really?

The New York Trilogy by Paul Auster. I wouldn’t have thought this was the stuff of the five-finger discount.

Steal this Book did not crack the top seven, though it did receive honorable mention, along with Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, Paulo Coelho’s The Alchemist, and “anything by Martin Amis.” Having been a poor college student myself once (not that I lifted my books!), and having taught many a cash-strapped undergrad, I’d assume a good number of the missing Fitzgeralds and Hemingways left bookstores in the hands of thieves bearing syllabi.

A 2009 Guardian list gives us an entirely different image of British book thieves with a penchant for boxer Lenny McLean’s memoirs, Yolanda Celbridge’s “modern S&M classic” The Taming of Trudi, comic books Tintin and Asterix, Banksy’s coffee table book Wall and Piece, and Harry Potter. Hoffman comes in at number six.

When it comes to books stolen from libraries, on the other hand, Huber points out this dynamic: “library theft leans more toward the practical than the popular, whereas bookstore theft leans toward the popular.” The top seven here include expensive art books, The Bible, The Guinness Book of World Records, textbooks/reference books/exam prep books, and, naturally, books on university reading lists. Also, Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition and “other racy books/magazines”—many stolen, perhaps, to avoid the embarrassment of prying librarian eyes.

We do not assume that you, dear upstanding reader, have ever stolen a book, or anything else. And yet, did you find anything on these lists surprising? (I thought Henry Miller might make the cut.…) What books would you expect to see stolen often that didn’t appear? What about a list of “most borrowed” (and maybe never returned) books from friends/acquaintances/family/roommates? Let us know your thoughts below.

via Vintage/Anchor/Kottke

Related Content:

The 20 Most Influential Academic Books of All Time: No Spoilers

28 Important Philosophers List the Books That Influenced Them Most During Their College Days

The 10 Greatest Books Ever, According to 125 Top Authors (Download Them for Free)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness