Tucked in the afterward of the second, 1982 edition of Hubert Dreyfus and Paul Rabinow’s Michel Foucault: Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, we find an important, but little-known essay by Foucault himself titled “The Subject and Power.” Here, the French theorist offers what he construes as a summary of his life’s work: spanning 1961’s Madness and Civilization up to his three-volume, unfinished History of Sexuality, still in progress at the time of his death in 1984. He begins by telling us that he has not been, primarily, concerned with power, despite the word’s appearance in his essay’s title, its arguments, and in nearly everything else he has written. Instead, he has sought to discover the “modes of objectification which transform human beings into subjects.”

This distinction may seem abstruse, a needlessly wordy matter of semantics. It is not so for Foucault. In key critical difference lies the originality of his project, in all its various stages of development. “Power,” as an abstraction, an objective relation of dominance, is static and conceptual, the image of a tyrant on a coin, of Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan seated on his throne.

Subjection, subjectification, objectivizing, individualizing, on the other hand—critical terms in Foucault’s vocabulary—are active processes, disciplines and practices, relationships between individuals and institutions that determine the character of both. These relationships can be located in history, as Foucault does in example after example, and they can also be critically studied in the present, and thus, perhaps, resisted and changed in what he terms “anarchistic struggles.”

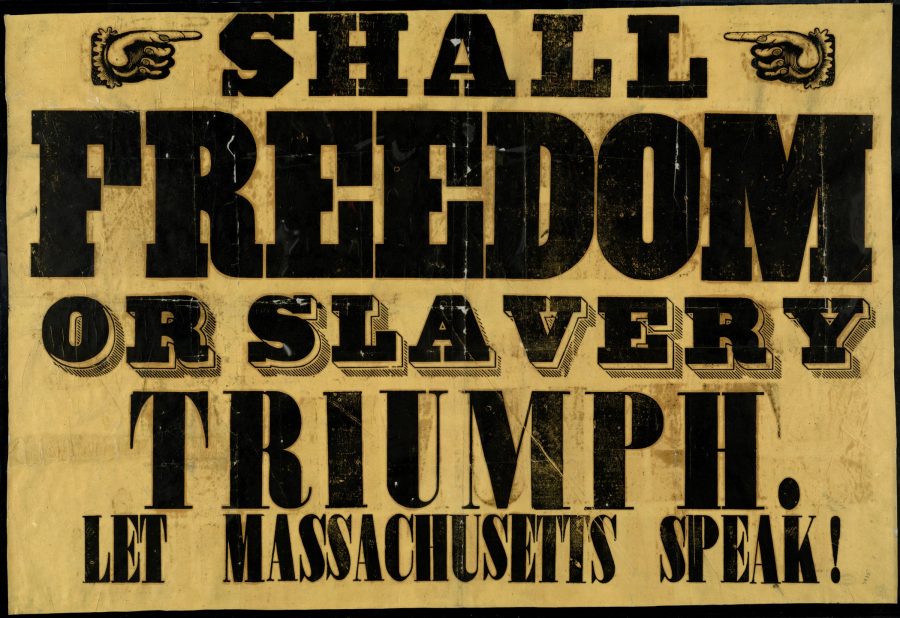

Foucault calls for a “new economy of power relations,” and a critical theory that takes “forms of resistance against different forms of power as a starting point.” For example, in approaching the carceral state, we must examine the processes that divide “the criminals and the ‘good boys,’” processes that function independently of reason. How is it that a system can create classes of people who belong in cages and people who don’t, when the standard rational justification—the protection of society from violence—fails spectacularly to apply in millions of cases? From such excesses, Foucault writes, come two “’diseases of power’—fascism and Stalinism.” Despite the “inner madness” of these “pathological forms” of state power, “they used to a large extent the ideas and the devices of our political rationality.”

People come to accept that mass incarceration, or invasive medical technologies, or economic deprivation, or mass surveillance and over-policing, are necessary and rational. They do so through the agency of what Foucault calls “pastoral power,” the secularization of religious authority as integral to the Western state.

This form of power cannot be exercised without knowing the inside of people’s minds, without exploring their souls, without making them reveal their innermost secrets. It implies a knowledge of the conscience and an ability to direct it.

In the last years of Foucault’s life, he shifted his focus from institutional discourses and mechanisms—psychiatric, carceral, medical—to disciplinary practices of self-control and the governing of others by “pastoral” means. Rather than ignoring individuality, the modern state, he writes, developed “as a very sophisticated structure, in which individuals can be integrated, under one condition: that this individuality would be shaped in a new form and submitted to a set of very specific patterns.” While writing his monumental History of Sexuality, he gave a series of lectures at Berkeley that explore the modern policing of the self.

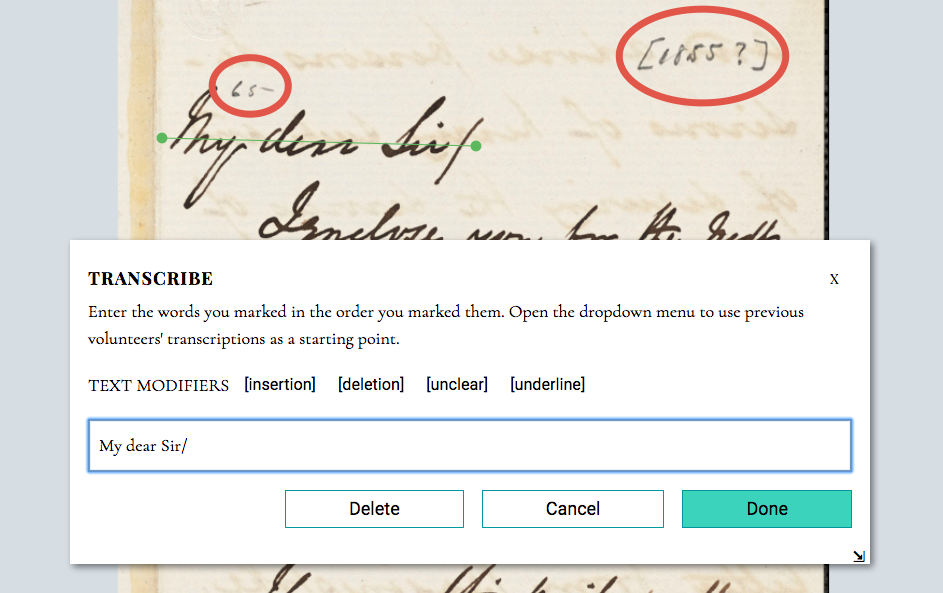

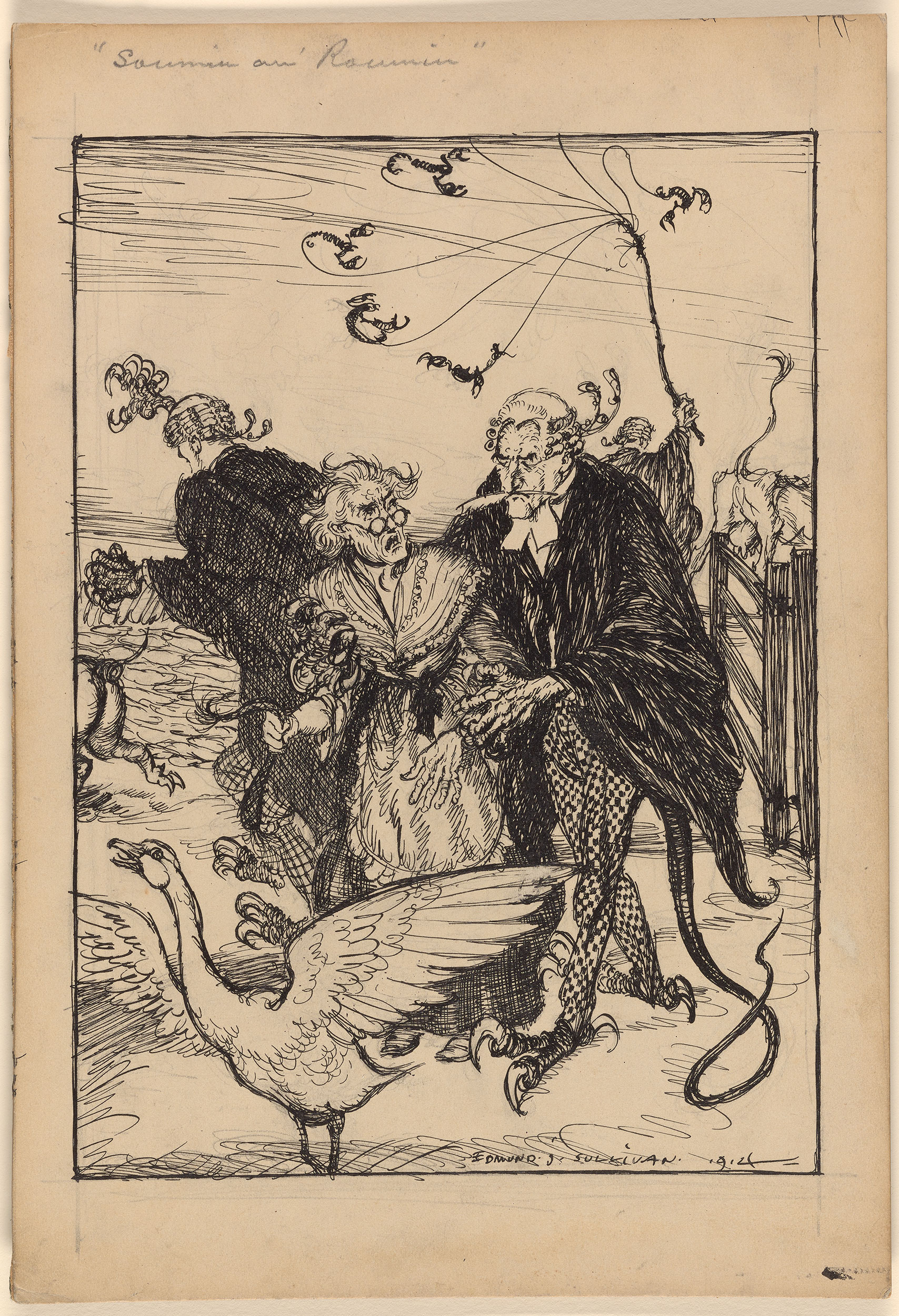

In his lectures on “Truth and Subjectivity” (1980), Foucault looks at forms of interrogation and various “truth therapies” that function as subtle forms of coercion. Foucault returned to Berkeley in 1983 and delivered the lecture “Discourse and Truth,” which explores the concept of parrhesia, the Greek term meaning “free speech,” or as he calls it, “truth-telling as an activity.” Through analysis of the tragedies of Euripides and contemporary democratic crises, he reveals the practice of speaking truth to power as a kind of tightly controlled performance. Finally, in his lecture series “The Culture of the Self,” Foucault discusses ancient and modern practices of “self care” or “the care of the self” as technologies designed to produce certain kinds of tightly bounded subjectivities.

You can hear parts of these lectures above or visit our posts with full audio above. Also, over at Ubuweb, download the lectures as mp3s, and hear several earlier talks from Foucault in French, dating all the way back to 1961.

When he began his final series of talks in 1980, the philosopher was asked in an interview with the Daily Californian about the motivations for his critical examinations of power and subjectivity. His reply speaks to both his practical concern for resistance and his almost utopian belief in the limitless potential for human freedom. “No aspect of reality should be allowed to become a definitive and inhuman law for us,” Foucault says.

We have to rise up against all forms of power—but not just power in the narrow sense of the word, referring to the power of a government or of one social group over another: these are only a few particular instances of power.

Power is anything that tends to render immobile and untouchable those things that are offered to us as real, as true, as good.

Read Foucault’s statement of intent, his essay “The Subject and Power,” and learn more about his life and work in the 1993 documentary below.

Foucault’s lecture series will be added to our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Related Content:

Watch a “Lost Interview” With Michel Foucault: Missing for 30 Years But Now Recovered

Michel Foucault and Alain Badiou Discuss “Philosophy and Psychology” on French TV (1965)

Clash of the Titans: Noam Chomsky & Michel Foucault Debate Human Nature & Power on Dutch TV, 1971

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness