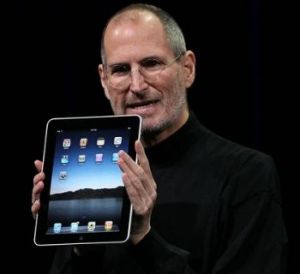

Today we have a guest post by William Rankin, director of educational innovation, associate professor of medieval literature, and Apple Distinguished Educator, Abilene Christian University. ACU was the first university in the world to announce a comprehensive one-to-one initiative based on iPhones and iPod touches designed to explore the impact of mobility in education. For the past year, they have been considering the future of the textbook. Rankin, who made a brief appearance on NBC Nightly News last night, does a great job here of putting the new Apple iPad in historical context and suggesting why it may solve the great informational problems of our age.

Today we have a guest post by William Rankin, director of educational innovation, associate professor of medieval literature, and Apple Distinguished Educator, Abilene Christian University. ACU was the first university in the world to announce a comprehensive one-to-one initiative based on iPhones and iPod touches designed to explore the impact of mobility in education. For the past year, they have been considering the future of the textbook. Rankin, who made a brief appearance on NBC Nightly News last night, does a great job here of putting the new Apple iPad in historical context and suggesting why it may solve the great informational problems of our age.

It may seem strange in the wake of a major tech announcement to turn to the past—570 years in the past and beyond — but to consider the role of eBooks and specifically of Apple’s new iPad, I think such a diversion is necessary. Plus, as regular readers of Open Culture know, technology is at its best not when it sets us off on some isolated yet sparkling digital future, but when it connects us more fully to our humanity — to our history, our interrelatedness, and our culture. I want to take a moment, therefore, to look back before I look forward, considering the similarities between Gutenberg’s revolution and recent developments in eBook technologies and offering some basic criteria we can borrow from history to assess whether these new technologies — including Apple’s iPad — are ready to propel us into information’s third age.

In the world before Gutenberg’s press — the first age — information was transmitted primarily in a one-to-one fashion. If I wanted to learn something from a person, I typically had to go to that person to learn it. This created an information culture that was highly personal and relational, a characteristic evidenced in apprenticeships and in the teacher/student relationships of the early universities. This relational characteristic was true even for textual information. The manual technology behind the production and copying of books and the immense associated costs meant that it was difficult for books to proliferate. To see a book — if I couldn’t afford to have my own copy hand-made, a proposition requiring the expenditure of a lifetime’s worth of wages for the average person — meant that I had to go visit the library that owned it. Even then, I might not be allowed to see it if I didn’t have a privileged relationship with its owners. So while the first age was rich in information (a truth that has nothing to do with my personal bias as a medievalist), its primary challenge involved access.

Gutenberg’s revolution, ushering in the second age, solved that problem. Driven by one of the first machines to enable mass-production, information could proliferate for the first time. Multiple copies of books could be produced quickly and relatively cheaply — Gutenberg’s Bible was available at a cost of only three years’ wages for the average clerk — and this meant that books took on a new role in culture. This was the birth of mass media. Libraries exploded from having tens or perhaps a few hundred books to having thousands. Or tens of thousands. Or millions. And this abundance led to three distinct revolutions in culture. Though the university initially fought its introduction, the printed textbook provided broad access to information that, for the first time, promised the possibility of universal education. Widespread access to bibles and theological texts fueled significant transformations in religion across the Western Hemisphere. And access to information, philosophy, and news led to the dismantling of old political hierarchies and some of the first experiments with democracy (have you ever stopped to notice how many of the American revolutionaries were involved in printing and publishing?). (more…)