Living and filmgoing here in Los Angeles, I seize every opportunity to watch Los Angeles Plays Itself, Thom Andersen’s extensive and entertaining documentary on the uses and abuses of the city throughout cinema history. In one passage, Andersen tracks the strikingly various roles of George Wyman’s 1893 Bradbury Building downtown: Deckard’s apartment in Blade Runner, Marlowe’s office in Marlowe, the place where Tom meets Autumn in (500) Days of Summer. “The movies discovered the Bradbury Building before the architectural historians did,” the narration tells us. “In China Girl, it played the Hotel Royale in Mandalay, Burma. The following year, in The White Cliffs of Dover, it played a London military hospital overflowing with wounded soldiers.” We then see the climactic scene of a film called D.O.A. which, dramatically heightened even by the standards of film noir, depicts a poisoned man chasing his own murderer up the stairs of the building’s darkened but still unmistakable atrium.

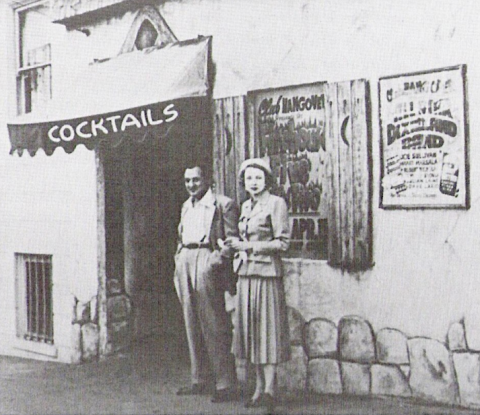

“Fatally poisoned by a luminous toxin slipped into his drink at a jazz club,” so Andersen’s narrator summarizes, “Frank Bigelow has one day before dying to track down his killer, and he finds him at the Phillips Import-Export Company… Room 427.” Few viewers of the documentary will already have seen D.O.A.; the rest surely feel intrigued enough to track it down. Fortunately, they can watch the complete 1950 film free online, since it fell into the public domain in 1977. Called “one of the most accomplished, innovative, and downright twisted entrants to the film noir genre” by the BBC’s David Wood, Hungarian expat director Rudolph Maté’s third picture has, like many of its artistic relatives, experienced a respectful re-evaluation since raising groans from critics with, among other things, the claim of being “As Excitingly Different As Its Title!” Salon’s Michael Sragow calls it an example of a “high-concept movie before its time,” one that certainly does have more to offer you on your film noir Friday than just a neat building.

Related Content:

Detour: The Cheap, Rushed Piece of 1940s Film Noir Nobody Ever Forgets

Fritz Lang’s “Licentious, Profane, Obscure” Noir Film, Scarlet Street (1945)

100 Greatest Posters of Film Noir

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.