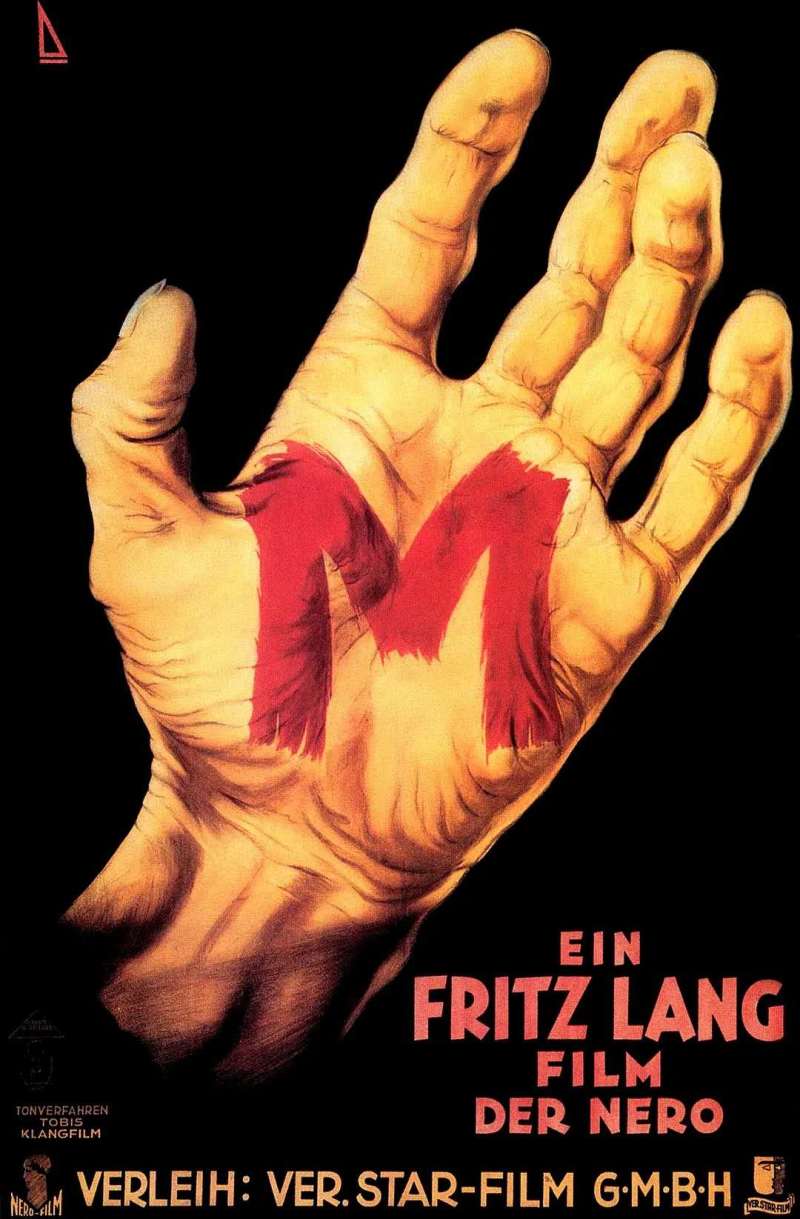

When Jean-Luc Godard asked the Austrian filmmaker Fritz Lang in 1961 to name his greatest film, the one most likely to last, Lang did not hesitate.

“M,” he said.

Made in 1931, near the end of the Weimar Republic, M is Lang’s brilliant link between silent film and talkies, and between German Expressionism and what would eventually be called Film Noir. It tells the story of a Berlin society caught up in hysteria over a series of child murders, and of the massive mobilization — by police and criminals alike — to catch the killer.

The Hungarian actor Peter Lorre plays Hans Beckert, the mentally disturbed murderer. Lorre worked on the film in the daytime while performing onstage in Bertolt Brecht’s production of Mann ist Mann in the evenings. His striking performance in M would catapult him to international stardom.

The script was written by Lang and his wife, Thea Von Harbou. It was inspired by a series of mass murders, culminating in a sensational case of serial child killings in Düsseldorf. In a 1931 article, Lang wrote:

The epidemic series of mass murders of the last decade with their manifold and dark side effects had constantly absorbed me, as unappealing as their study may have been. It made me think of demonstrating, within the framework of a film story, the typical characteristics of this immense danger for the daily order and the ways of effectively fighting them. I found the prototype in the person of the Düsseldorf serial murderer and I also saw how here the side effects exactly repeated themselves, i.e. how they took on a typical form. I have distilled all typical events from the plethora of materials and combined them with the help of my wife into a self-contained film story. The film M should be a document and an extract of facts and in that way an authentic representation of a mass murder complex.

Although M was not a great box office success when it was released in Germany in 1931, the film gradually grew in stature and is now firmly established as one of the masterpieces of 20th century cinema. The brilliance of the film’s narrative structure, its classic visual images (the killer’s shadow appearing on a poster announcing a reward for his capture, a child’s balloon caught in a power line, Lorre’s bulging eyes as he discovers a chalk “M” on his shoulder) and its inventive use of sound, for example in the serial killer’s ominous whistling of Grieg’s Peer Gynt, have made M one of the most studied and imitated films ever made.

In 1959 M was re-released in truncated form, and for several decades afterward audiences were shown a badly altered 89-minute version. A restoration project was mounted in the 1990s. The 109-minute version above, a result of that project, is closer to Lang’s original film. It’s now housed in our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Related content:

Fritz Lang’s “Licentious, Profane, Obscure” Noir Film, Scarlet Street (1945)