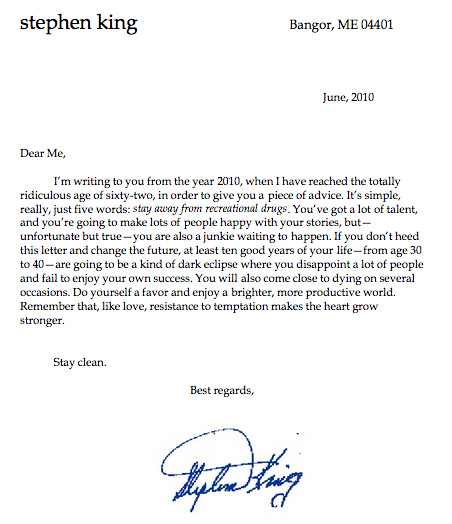

By the 1980s, it looked like Stephen King had everything. He had authored a series of bestsellers — Carrie, The Shining, Cujo – and turned them into blockbuster movies. He had a big, 24-room house. Plenty of cash in the bank. All the trappings of that American Dream. And yet … and yet … he was angry and depressed, smoking two packs of cigarettes a day, drinking lots of beer, snorting coke, and entertaining suicidal thoughts. It’s no wonder then that the author, who sobered up during the late 80s, contributed the letter above to a 2011 collection called Dear Me: A Letter to My 16-Year-Old Self. Edited by Joseph Galliano, the book asked 75 celebrities, writers, musicians, athletes, and actors this question: “If as an adult, you could send a letter to your younger self, what words of guidance, comfort, advice or other message would you put in it?” In King’s case, the advice was short, sweet, to the point. In essence, a mere five words.

To view the letter in a larger format, click here.

via Flavorwire

Related Content:

Stephen Fry: What I Wish I Had Known When I Was 18

Radiohead’s Thom Yorke Gives Teenage Girls Endearing Advice About Boys (And Much More)

Stephen King Reads from His Upcoming Sequel to The Shining