Dave Eggers, author of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, has a new book coming out in early October, The Circle, a novel about “a young woman who goes to work at an omnipotent technology company and gets sucked into a corporate culture that knows no distinction between work and life, public and private.” Breaking with tradition, The New York Times has placed the novel’s cover on the cover of its own Sunday Magazine. It has also printed a lengthy excerpt from the book. Read it online here, or listen right below (or on iTunes) to a reading of the excerpt by actor Don Graham. It runs 46 minutes.

The Stunt That Got Elvis Costello Banned From Saturday Night Live (1977)

One of the defining moments in Elvis Costello’s career happened on December 17, 1977, when he appeared on Saturday Night Live. Costello was 23 years old. His debut album, My Aim Is True, had just come out in America a month earlier. When the Sex Pistols were unable to appear on the show as planned (see their last live concert here), Costello and his recently formed band, the Attractions, got their big break.

They were supposed to play his single “Less Than Zero,” a catchy tune about a loathsome politician in England. But only a few bars into the song, Costello put a stop to it. “I’m sorry, ladies and gentlemen,” he said, “but there’s no reason to do this song here.”

At that point he and the band launched into “Radio Radio,” a song that takes a jab at corporate-controlled broadcasting. Saturday Night Live producer Lorne Michaels was furious. According to some reports, he raised his middle finger at Costello and kept it up until the unapproved song was over. Costello was banned from the show for nearly 12 years. You can learn more about the incident by watching this video from the Daily Guru:

The rift between Costello and Michaels eventually healed, and Costello was invited to appear again on Saturday Night Live in the spring of 1989. Ten years after that, on SNL’s 25th anniversary show, Costello went on the show again and parodied his notorious 1977 appearance by bursting onstage while the Beastie Boys were playing “Sabotage” and ordering them to stop. He and the Boys then launched into a raucous version of “Radio Radio”:

In an interview this month with Details magazine, Costello talks a little about the 1977 incident. “They’ve run that clip forever,” he says, “and every time anybody does anything outrageous on that show, I get name-checked. But I was copying Jimi Hendrix. Hendrix had done the same thing on the Lulu Show, when he went into an unscheduled number. I remember seeing it and going, ‘What the hell’s going on?’ ” To see for yourself what Costello is talking about, visit our post, Jimi Hendrix Wreaks Havoc on the Lulu Show, Gets Banned From BBC.

Also see: 5 Musical Guests Banned From Saturday Night Live: From Sinead O’Connor to Frank Zappa

Related Content:

Elvis Costello Sings “Penny Lane” for Sir Paul McCartney

William S. Burroughs on Saturday Night Live, 1981

Watch Janis Joplin’s Final Interview Get Reborn as an Animated Cartoon

Four days before her death, Janis Joplin spoke with Howard Smith of the Village Voice in what was to be her last interview.

Their conversation has been resurrected as a four minute animation for PBS Digital Studios’ Blank on Blank series. The cartoon Janis bears a close resemblance to Gloria Steinem, an uncomfortable fit once the topic turns from her sadness at critical rejection to the sisterhood’s alleged withholding of affection.

Smith hits his subject with some leading questions that smack of the myriad ways Women’s Lib was distorted by even the liberal media of the time: “It seems to bother a lot of Women’s Lib people that you’re so upfront sexually,” he muses.

No need to take that one at anything less than face value…

Joplin allowed herself to be led, tossing off several statements that animator Patrick Smith faithfully illustrates. (In my opinion the wounded female drummers rock far more than pregnancy and vacuums, his shorthand for “settling.” )

When later, Joplin timidly asks if “all that $#*% I said about chicks” sounded bad, Smith reassures her that no, she said what she wanted to say. Perhaps he got what he wanted her to say.

As commenter heyitsmoi observed on YouTube, “It’s always bothered me when people ask successful women to comment on how some other women don’t like them. I’ve yet to hear a successful man to be asked why other men don’t like him, even though there’s sure to be plenty. Women seem to constantly be put in this defensive position where they can’t answer the question without making it sound like all women are jealous beasts who can’t handle that some woman made it, and that’s simply not true.”

If you’re left feeling vaguely queasy, I suggest “Stiletto Power,” Blank on Blank’s take on Larry Grobel’s 1994 interview with Farrah Fawcett. Grobel’s approach seemed to have been one of turn on the tape recorder and then get out of the way. Mission accomplished. The resulting monologue is as ferocious as it is funny.

Related Content:

Animations Revive Lost Interviews with David Foster Wallace, Jim Morrison & Dave Brubeck

Remembering Janis Joplin: Some Classic Live Performances and Previews of a New Joplin Musical

‘Beastie Boys on Being Stupid’: An Animated Interview From 1985

Ayun Halliday has fond feelings for both of the women featured in the above article . Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Hergé Draws Tintin in Vintage Footage (and What Explains the Character’s Enduring Appeal)

“Tintin addicts are a mixed bunch,” writes New Yorker critic Anthony Lane, profiling the beloved plus fours-clad, quiff-topped adventurer and thereby revealing himself as one of the afflicted. “Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson [have] a three-picture deal to bring Tintin to the big screen. I once heard Hugh Grant declare on a radio program that if he could take only one book to a desert island it would be King Ottokar’s Sceptre (1939). [ … ] General de Gaulle declared that Tintin was his only international rival — he was envious, perhaps, not just of Tintin’s fame but of the defiantly positive attitude that he came to represent.” Despite coming from America, one of the few countries never to have taken wholeheartedly to the character, I too have read and re-read the 23 full-length comic books (or as we call them nowadays, graphic novels) in which he stars, and I too envy his qualities, especially the useful amorphousness of his identity: neither man nor boy; neither traditional nor modern; presumably Belgian, though for practical purposes stateless and apolitical; ostensibly a reporter, but no apparent need ever to file a story.

The late Harry Thompson surely ranks as a top Tintin addict. A radio and television producer, comedy writer, novelist, and creator of Have I Got News for You, he also greatly advanced the widespread avocation of English-language Tintinology with his book Tintin: Hergé and his Creation, published in 1991. Three years later, he would star in this episode of London Weekend Television’s documentary series Opening Shot on Tintin and his creator (part one at the top, click for two and three). His analysis swiftly assures any adult reader just how and why they should go about picking up and appreciating the truly painstaking craftsmanship of these comics they so relished in their youth. The broadcast also features commentary from Tintin’s English translators and, through archival footage, from Georges “Hergé” Remi himself (seen drawing Tintin just above, and his companion Captain Haddock below). Finally, we hear from more typical Tintin readers in man-on-the-street interviews — or rather, precocious-British-child-in-the-bookstore interviews: “My favorite character is Snowy, because he says really rude things.” “My favorite book is Tintin in America, because I like red Indians.” How many of these kids, nearly two decades on, can have resisted the siren song of Tintinology themselves?

Related Content:

The Inscrutable Imagination of the Late Comic Artist Mœbius

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

Steve Jobs on the Rise of the Personal Computer: A Rare 1990 Interview

In early 1990 Steve Jobs granted a very rare interview to the makers of a PBS NOVA miniseries called The Machine that Changed the World.

The producers of the series had a tough time getting Jobs to talk with them. They had already interviewed Bill Gates, Steve Wozniak and most of the other founding fathers of the personal computing revolution, but the reclusive Jobs brushed off all requests. “As we started the series,” writes Nancy Linde at the NOVA Web site, “we were warned time and time again. ‘You ‘ll never get Steve Jobs on camera.’ ” After multiple requests, Jobs finally replied with a terse “No, thank you.” Linde continues:

But we had an ace up our sleeve by the name of Robert Noyce. A legend in the computer world as the co-inventor of the microchip and co-founder of Intel, Bob Noyce was a strong supporter of The Machine That Changed the World and served on our advisory board. Like most in Silicon Valley, Steve Jobs revered Bob Noyce, and a one-paragraph letter from Noyce changed Jobs’ “no” into a “yes,” giving our series one of a limited number of interviews Steve Jobs gave in his short lifetime.

At the time of the interview, Jobs was 35 years old and about midway through his 11-year exile from Apple. He was working with NeXT, the computer company he founded after being pushed out of Apple in 1985. In keeping with the theme of the miniseries, the interview deals mostly with the big picture. Jobs talks about the role of the computer in human life, and about the emergence and evolution of personal computing. He tells the story of how he and his early friend Wozniak (referred to in the interview as “Woz”) turned a hobby into a business and developed the Apple I and Apple II computers. He very briefly touches on the first two drivers of the personal computing revolution — spreadsheets and desktop publishing — before talking at length about the revolution that was yet to come: networked computing. The World Wide Web had barely been created in 1990, and Jobs is fairly prescient in his predictions of how the linking of computers would change the world.

The interview is presented above in raw form. You can read a transcript of the conversation at the WGBH Web site.

Related Content:

Steve Jobs Demos the First Macintosh in 1984

Steve Jobs Narrates the First “Think Different” Ad (Never Aired)

Learn to Code with Harvard’s Intro to Computer Science Course And Other Free Tech Classes

North Carolina County Celebrates Banned Book Week By Banning Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man … Then Reversing It

We’re smack in the middle of Banned Books Week, and one particular case of book-banning has received a lot of attention lately, that of Ralph Ellison’s classic 1952 novel Invisible Man, which was censored by the Randolph County, NC school board last week. In response to one parent’s complaint, the board assessed the book, found it a “hard read,” and voted 5–2 to remove it from the high school libraries (prompting the novel’s publisher to give copies away for free to students). One board member stated that he “didn’t find any literary value” in Ellison’s novel, a judgment that may have raised the eyebrows of the National Book Award judges who awarded Ellison the honor in 1953, not to mention the 200 authors and critics who in 1965 voted the novel “the most distinguished single work published in the last twenty years.”

After widespread public outcry, the Randolph County reversed the decision in a special session yesterday. In light of the book’s newfound notoriety after this story, we thought we’d revisit a Paris Review interview Ellison gave in 1954. The interviewers press Ellison on what they see as some of the novel’s weaknesses, but describe Ellison’s masterwork as “crackling, brilliant, sometimes wild, but always controlled.” Below are some highlights from this rich conversation. This interview would not likely sway those shamefully unlettered school board members, but fans of Ellison and those just discovering his work will find much here of merit. Ellison, also an insightful literary critic and essayist, discusses at length his intentions, influences, and theories of literature.

- On his literary influences:

Ellison, who says he “became interested in writing through incessant reading,” cites a number of high modernist writers as direct influences on his work. T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land piqued his interest in 1935, and in the midst of the Depression, while he and his brother “hunted and sold game for a living” in Dayton OH, Ellison “practiced writing and studied Joyce, Dostoyevsky, Stein, and Hemingway.” He especially liked Hemingway for the latter’s authenticity.

I read him to learn his sentence structure and how to organize a story. I guess many young writers were doing this, but I also used his description of hunting when I went into the fields the next day. I had been hunting since I was eleven, but no one had broken down the process of wing-shooting for me, and it was from reading Hemingway that I learned to lead a bird. When he describes something in print, believe him; believe him even when he describes the process of art in terms of baseball or boxing; he’s been there.

- On literature as protest

Ellison began Invisible Man in 1945, before the Civil Rights movement got going. He drew much of his sense of the novel as a form of social protest from literary sources, claiming that he recognized “no dichotomy between art and protest.”

Dostoyevsky’s Notes from Underground is, among other things, a protest against the limitations of nineteenth-century rationalism; Don Quixote, Man’s Fate, Oedipus Rex, The Trial—all these embody protest, even against the limitation of human life itself. If social protest is antithetical to art, what then shall we make of Goya, Dickens, and Twain?

All novels are about certain minorities: the individual is a minority. The universal in the novel—and isn’t that what we’re all clamoring for these days?—is reached only through the depiction of the specific man in a specific circumstance.

- On the role of myth and folklore in literature:

Ellison adapts a tremendous amount of black American folklore in Invisible Man, from folk tales to the blues, to give the novel much of its voice and structure. His use of folk forms springs from his sense that “Negro folklore, evolving within a larger culture which regarded it as inferior, was an especially courageous expression” as well as his reading of ritual in the modernist masters he admired. Of the use of folklore and myth, Ellison says,

The use of ritual is equally a vital part of the creative process. I learned a few things from Eliot, Joyce and Hemingway, but not how to adapt them. When I started writing, I knew that in both “The Waste Land” and Ulysses, ancient myth and ritual were used to give form and significance to the material; but it took me a few years to realize that the myths and rites which we find functioning in our everyday lives could be used in the same way. … People rationalize what they shun or are incapable of dealing with; these superstitions and their rationalizations become ritual as they govern behavior. The rituals become social forms, and it is one of the functions of the artist to recognize them and raise them to the level of art.

- On the moral and social function of literature:

Ellison has quite a lot to say in the interview about what he sees as the moral duty of the novelist to address social problems, which he relates to a nineteenth century tradition (referencing another famously banned book, Huckleberry Finn). Ellison faults the contemporary literature of his day for abandoning this moral dimension, and he makes it clear that his intention is to see the social problems he depicts as great moral questions that American literature should address.

One function of serious literature is to deal with the moral core of a given society. Well, in the United States the Negro and his status have always stood for that moral concern. He symbolizes among other things the human and social possibility of equality. This is the moral question raised in our two great nineteenth-century novels, Moby-Dick and Huckleberry Finn. The very center of Twain’s book revolves finally around the boy’s relations with Nigger Jim and the question of what Huck should do about getting Jim free after the two scoundrels had sold him. There is a magic here worth conjuring, and that reaches to the very nerve of the American consciousness—so why should I abandon it? …Perhaps the discomfort about protest in books by Negro authors comes because since the nineteenth century, American literature has avoided profound moral searching. It was too painful and besides there were specific problems of language and form to which the writers could address themselves. They did wonderful things, but perhaps they left the real problems untouched.

The full Paris Review interview is well worth reading.

Related Content:

Ralph Ellison Reads from His Novel-in-Progress, Juneteenth, in Rare Video Footage (1966)

74 Free Banned Books (for Banned Books Week)

The Paris Review Interviews Now Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Richard Feynman Gets Jazzed Explaining How Rubber Bands Work

Back in 1983, the BBC aired Fun to Imagine, a television series hosted by Richard Feynman that used physics to explain how the everyday world works. Here, in language that makes sense to anyone with a basic grounding in science, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist answered questions like, Why can’t tennis balls bounce forever? What are we really seeing when we look in the mirror? And, as shown above, why are rubber bands stretchy? The clip comes from Fun to Imagine, and thanks to this dedicated BBC website, you can watch online all six videos in the series, each running about 12 minutes. (If you have any difficulty viewing them at the BBC, simply watch the all-in-one video below.) But beware, Feynman’s enthusiasm for science is contagious. So watch the clips at your own risk, and be prepared to start playing with bouncy, stretchy things during your free time, hopefully with a big smile on your face.

Related Content:

Richard Feynman Presents Quantum Electrodynamics for the NonScientist

The Famous Feynman Lectures on Physics: The New Online Edition (in HTML5)

‘The Character of Physical Law’: Richard Feynman’s Legendary Lecture Series at Cornell, 1964

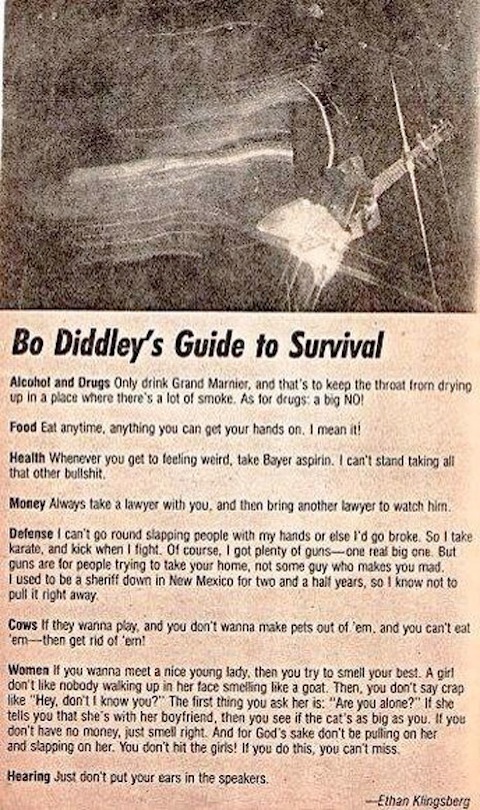

Bo Diddley’s Essential Tips for Surviving Life & the Music Business

Some people think Chuck Berry invented rock and roll. Chuck Berry sure thinks so. But I say it was Bo Diddley. At least Diddley invented the rock and roll I love—throbbing, dirty, hypnotic, hovering in some space between the blues, gospel and African rhythms but also with its feet firmly planted on any industrial city streetcorner. Bo Diddley invented irony in rock (his first band was called “The Hipsters”). Bo Diddley never pandered to the teenybopper crowd (though he did go commercial in the 80s). Even his biggest hits have about them an otherworldly air of echo‑y weirdness, with their signature beat and one-note drone. Also something vaguely sleazy and maybe a little sinister, essential elements of rock and roll worthy of the name.

So, as a man who made his own rhythm, his own tones, his own studio, and his own guitar—who was so much his own man that one of his best known songs is named after him—it stands to reason that he would also make his own set of rules for surviving the music business. Called “Bo Diddley’s Guide to Survival,” the list covers all the bases: drugs and booze (“NO!”), food (“anything you can get your hands on”), health, money, defense, cows, women, and hearing. What more is there, really?

The list, clearly part of a magazine feature, has circulated on the internet for some time, but no one has managed to track down the source. It’s probably genuine, though; it sounds like the perfect mix of the down-to-earth and far-out funny that was Bo Diddley. I’m particularly intrigued by his very specific defense techniques (Elvis obviously took notes). It is true, by the way, that Diddley once served as a sheriff in New Mexico, a fact that adds so much to the mystique. Where “Defense” and “Women” get lengthy (and respectful) treatments, his succinct take on “Hearing” is as practical as it gets.

See the original list at the top and read the full transcript below. As you do, listen to the timeless weirdness of “Bo Diddley” above. There’s nothing else like it.

Alcohol and Drugs Only drink Grand Marnier, and that’s to keep the throat from drying up in a place where there’s a lot of smoke. As for drugs: a big NO!

Food Eat anytime, anything you can get your hands on. I mean it!

Health Whenever you get to feeling weird, take Bayer aspirin. I can’t stand taking all that other bullshit.

Money Always take a lawyer with you, and then bring another lawyer to watch him.

Defense I can’t go around slapping people with my hands or else I’d go broke. So I take karate, and kick when I fight. Of course, I got plenty of guns — one real big one. But guns are for people trying to take your home, not some guy who makes you mad. I used to be a sheriff down in New Mexico for two and a half years, so I know not to pull it right away.

Cows If they wanna play, and you don’t wanna make pets out of ‘em, and you can’t eat ‘em — then get rid of ‘em!

Women If you wanna meet a nice young lady, then you try to smell your best. A girl don’t like nobody walking up in her face smelling like a goat. Then, you don’t say crap like “Hey, don’t I know you?” The first thing you ask her is: “Are you alone?” If she tells you that she’s with her boyfriend, then you see if the cat’s as big as you. If you don’t have no money, just smell right. And for God’s sake don’t be pulling on her and slapping on her. You don’t hit the girls! If you do this, you can’t miss.

Hearing Just don’t put your ears in the speakers.

Related Content:

Chuck Berry Takes Keith Richards to School, Shows Him How to Rock (1987)

Keith Richards Waxes Philosophical, Plays Live with His Idol, the Great Muddy Waters

A History of Rock ‘n’ Roll in 100 Riffs

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness