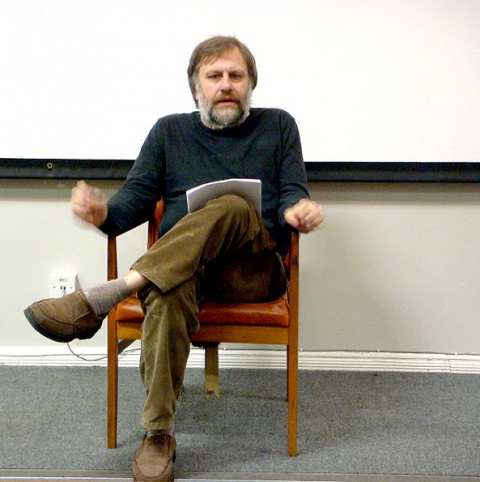

Fur has flown, claws and teeth were bared, and folding chairs were thrown! But of course I refer to the bristly exchange between those two stars of the academic left, Slavoj Žižek and Noam Chomsky. And yes, I’m poking fun at the way we—and the blogosphere du jour—have turned their shots at one another into some kind of celebrity slapfight or epic rap battle grudge match. We aim to entertain as well as inform, it’s true, and it’s hard to take any of this too seriously, since partisans of either thinker will tend to walk away with their previous assumptions confirmed once everyone goes back to their corners.

But despite the seeming cattiness of Chomsky and Žižek’s highly mediated exchanges (perhaps we’re drumming it up because a simple face-to-face debate has yet to occur, and probably won’t), there is a great deal of substance to their volleys and ripostes, as they butt up against critical questions about what philosophy is and what role it can and should play in political struggle. As to the former, must all philosophy emulate the sciences? Must it be empirical and consistently make transparent truth claims? Might not “theory,” for example (a word Chomsky dismisses in this context), use the forms of literature—elaborate metaphor, playful systems of reference, symbolism and analogy? Or make use of psychoanalytic and Marxian terminology in evocative and novel ways in serious attempts to engage with ideological formations that do not reveal themselves in simple terms?

Another issue raised by Chomsky’s critiques: should the work of philosophers who identify with the political left endeavor for a clarity of expression and a direct utility for those who labor under systems of oppression, lest obscurantist and jargon-laden writing become itself an oppressive tool and self-referential game played for elitist intellectuals? These are all important questions that neither Žižek nor Chomsky has yet taken on directly, but that both have obliquely addressed in testy off-the-cuff verbal interviews, and that might be pursued by more disinterested parties who could use their exchange as an exemplar of a current methodological rift that needs to be more fully explored, if never, perhaps, fully resolved. As Žižek makes quite clear in his most recent—and very clearly-written—essay-length reply to Chomsky’s latest comment on his work (published in full on the Verso Books blog), this is a very old conflict.

Žižek spends the bulk of his reply exonerating himself of the charges Chomsky levies against him, and finding much common ground with Chomsky along the way, while ultimately defending his so-called continental approach. He provides ample citations of his own work and others to support his claims, and he is detailed and specific in his historical analysis. Žižek is skeptical of Chomsky’s claims to stand up for “victims of Third World suffering,” and he makes it plain where the two disagree, noting, however, that their antagonism is mostly a territorial dispute over questions of style (with Chomsky as a slightly morose guardian of serious, scientific thought and Žižek as a sometimes buffoonish practitioner of a much more literary tradition). He ends with a dig that is sure to keep fanning the flames:

To avoid a misunderstanding, I am not advocating here the “postmodern” idea that our theories are just stories we are telling each other, stories which cannot be grounded in facts; I am also not advocating a purely neutral unbiased view. My point is that the plurality of stories and biases is itself grounded in our real struggles. With regard to Chomsky, I claim that his bias sometimes leads him to selections of facts and conclusions which obfuscate the complex reality he is trying to analyze.

………………….

Consequently, what today, in the predominant Western public speech, the “Human Rights of the Third World suffering victims” effectively mean is the right of the Western powers themselves to intervene—politically, economically, culturally, militarily—in the Third World countries of their choice on behalf of the defense of Human Rights. My disagreement with Chomsky’s political analyses lies elsewhere: his neglect of how ideology works, as well as the problematic nature of his biased dealing with facts which often leads him to do what he accuses his opponents of doing.

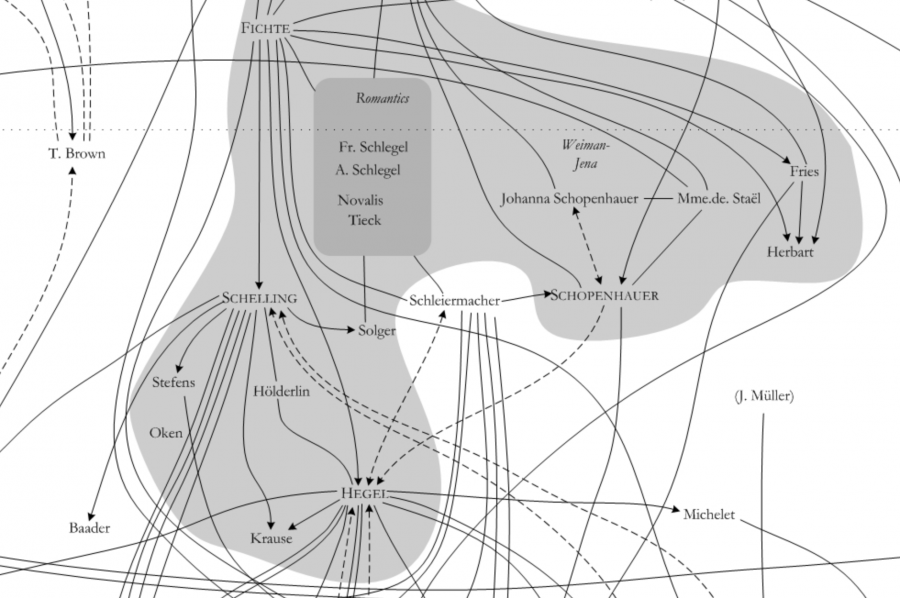

But I think that the differences in our political positions are so minimal that they cannot really account for the thoroughly dismissive tone of Chomsky’s attack on me. Our conflict is really about something else—it is simply a new chapter in the endless gigantomachy between so-called continental philosophy and the Anglo-Saxon empiricist tradition. There is nothing specific in Chomsky’s critique—the same accusations of irrationality, of empty posturing, of playing with fancy words, were heard hundreds of times against Hegel, against Heidegger, against Derrida, etc. What stands out is only the blind brutality of his dismissal

I think one can convincingly show that the continental tradition in philosophy, although often difficult to decode, and sometimes—I am the first to admit this—defiled by fancy jargon, remains in its core a mode of thinking which has its own rationality, inclusive of respect for empirical data. And I furthermore think that, in order to grasp the difficult predicament we are in today, to get an adequate cognitive mapping of our situation, one should not shirk the resorts of the continental tradition in all its guises, from the Hegelian dialectics to the French “deconstruction.” Chomsky obviously doesn’t agree with me here. So what if—just another fancy idea of mine—what if Chomsky cannot find anything in my work that goes “beyond the level of something you can explain in five minutes to a twelve-year-old” because, when he deals with continental thought, it is his mind which functions as the mind of a twelve-year-old, the mind which is unable to distinguish serious philosophical reflection from empty posturing and playing with empty words?

Related Content:

Noam Chomsky Slams Žižek and Lacan: Empty ‘Posturing’

Slavoj Žižek Responds to Noam Chomsky: ‘I Don’t Know a Guy Who Was So Often Empirically Wrong’

The Feud Continues: Noam Chomsky Responds to Žižek, Describes Remarks as ‘Sheer Fantasy’

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness