Image via Wikimedia Commons

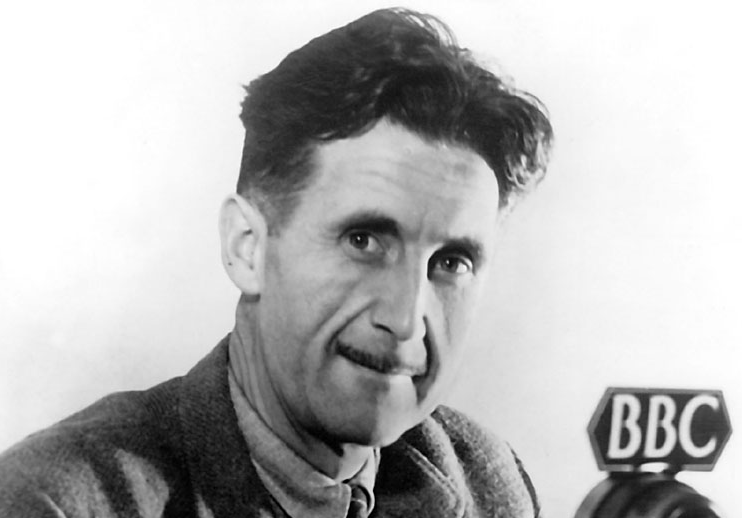

Most of the twentieth century’s notable men of letters — i.e., writers of books, of essays, of reportage — seem also to have, literally, written a great deal of letters. Sometimes their correspondence reflects and shapes their “real” written work; sometimes it appears collected in book form itself. Both hold true in the case of George Orwell, a volume of whose letters, edited by Peter Davison, came out last year. In it we find this missive, also published in full at The Daily Beast, sent in 1944 to one Noel Willmett, who had asked “whether totalitarianism, leader-worship etc. are really on the up-grade” given “that they are not apparently growing in [England] and the USA”:

I must say I believe, or fear, that taking the world as a whole these things are on the increase. Hitler, no doubt, will soon disappear, but only at the expense of strengthening (a) Stalin, (b) the Anglo-American millionaires and © all sorts of petty fuhrers of the type of de Gaulle. All the national movements everywhere, even those that originate in resistance to German domination, seem to take non-democratic forms, to group themselves round some superhuman fuhrer (Hitler, Stalin, Salazar, Franco, Gandhi, De Valera are all varying examples) and to adopt the theory that the end justifies the means. Everywhere the world movement seems to be in the direction of centralised economies which can be made to ‘work’ in an economic sense but which are not democratically organised and which tend to establish a caste system. With this go the horrors of emotional nationalism and a tendency to disbelieve in the existence of objective truth because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible fuhrer. Already history has in a sense ceased to exist, ie. there is no such thing as a history of our own times which could be universally accepted, and the exact sciences are endangered as soon as military necessity ceases to keep people up to the mark. Hitler can say that the Jews started the war, and if he survives that will become official history. He can’t say that two and two are five, because for the purposes of, say, ballistics they have to make four. But if the sort of world that I am afraid of arrives, a world of two or three great superstates which are unable to conquer one another, two and two could become five if the fuhrer wished it. That, so far as I can see, is the direction in which we are actually moving, though, of course, the process is reversible.

As to the comparative immunity of Britain and the USA. Whatever the pacifists etc. may say, we have not gone totalitarian yet and this is a very hopeful symptom. I believe very deeply, as I explained in my book The Lion and the Unicorn, in the English people and in their capacity to centralise their economy without destroying freedom in doing so. But one must remember that Britain and the USA haven’t been really tried, they haven’t known defeat or severe suffering, and there are some bad symptoms to balance the good ones. To begin with there is the general indifference to the decay of democracy. Do you realise, for instance, that no one in England under 26 now has a vote and that so far as one can see the great mass of people of that age don’t give a damn for this? Secondly there is the fact that the intellectuals are more totalitarian in outlook than the common people. On the whole the English intelligentsia have opposed Hitler, but only at the price of accepting Stalin. Most of them are perfectly ready for dictatorial methods, secret police, systematic falsification of history etc. so long as they feel that it is on ‘our’ side. Indeed the statement that we haven’t a Fascist movement in England largely means that the young, at this moment, look for their fuhrer elsewhere. One can’t be sure that that won’t change, nor can one be sure that the common people won’t think ten years hence as the intellectuals do now. I hope they won’t, I even trust they won’t, but if so it will be at the cost of a struggle. If one simply proclaims that all is for the best and doesn’t point to the sinister symptoms, one is merely helping to bring totalitarianism nearer.

You also ask, if I think the world tendency is towards Fascism, why do I support the war. It is a choice of evils—I fancy nearly every war is that. I know enough of British imperialism not to like it, but I would support it against Nazism or Japanese imperialism, as the lesser evil. Similarly I would support the USSR against Germany because I think the USSR cannot altogether escape its past and retains enough of the original ideas of the Revolution to make it a more hopeful phenomenon than Nazi Germany. I think, and have thought ever since the war began, in 1936 or thereabouts, that our cause is the better, but we have to keep on making it the better, which involves constant criticism.

Yours sincerely,

Geo. Orwell

Three years later, Orwell would write 1984. Two years after that, it would see publication and go on to generations of attention as perhaps the most eloquent fictional statement against a world reduced to superstates, saturated with “emotional nationalism,” acquiescent to “dictatorial methods, secret police,” and the systematic falsification of history,” and shot through by the willingness to “disbelieve in the existence of objective truth because all the facts have to fit in with the words and prophecies of some infallible fuhrer.” Now that you feel like reading the novel again, or even for the first time, do browse our collection of 1984-related resources, which includes the eBook, the audio book, reviews, and even radio drama and comic book adaptations of Orwell’s work.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to George Orwell

The Only Known Footage of George Orwell (Circa 1921)

George Orwell and Douglas Adams Explain How to Make a Proper Cup of Tea

George Orwell’s Political Views, Explained in His Own Words

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.