Helen Keller achieved notoriety not only as an individual success story, but also as a prolific essayist, activist, and fierce advocate for poor and marginalized people. She “was a lifelong radical,” writes Peter Dreier at Yes! magazine, whose “investigation into the causes of blindness” eventually led her to “embrace socialism, feminism, and pacifism.” Keller supported the NAACP and ACLU, and protested strongly against patronizing calls for her to “confine my activities to social service and the blind.” Her critics, she wrote, mischaracterized her ideas as “a Utopian dream, and one who seriously contemplates its realization indeed must be deaf, dumb, and blind.”

Twenty years later she found a different set of readers treating her ideas with contempt. This time, however, the critics were in Nazi Germany, and instead of simply disagreeing with her, they added her collection of essays, How I Became a Socialist, to a list of “degenerate” books to be burned on May 10, 1933. Such was the date chosen by Hitler for “a nationwide ‘Action Against the Un-German Spirit,’” writes Rafael Medoff, to take place at German Universities—“a series of public burnings of the banned books” that “differed from the Nazis’ perspective on political, social, or cultural matters, as well as all books by Jewish authors.”

Books burned included works by Einstein and Freud, H.G. Wells, Hemingway, and Jack London, Students hauled books out of the libraries as part of the spectacle. “The largest of the 34 book-burning rallies, held in Berlin,” Medoff notes, “was attended by an estimated 40,000 people.”

Not only were these demonstrations of anti-Semitism, but their contempt for ideas appealed broadly to the Nazi philosophy of “Blood and Soil,” a nationalist caricature of rural values over a supposedly “degenerate,” polyglot urbanism. “The soul of the German people can again express itself,” declared Joseph Goebbels ominously at the Berlin rally. “These flames not only illuminate the final end of an old era; they also light up the new.”

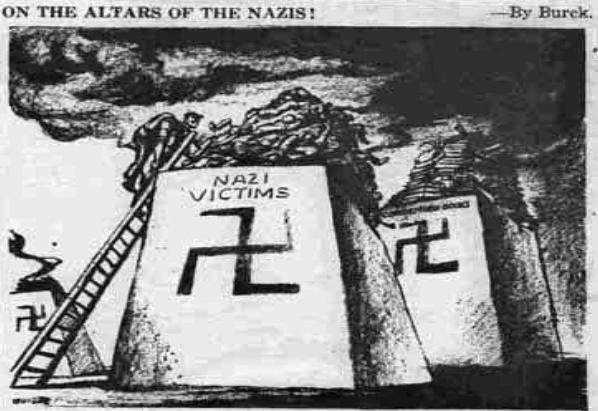

“Some American editorial responses” before and after the burnings, “made light of the event,” remarks the United States Holocaust Museum, calling it “silly” and “infantile.” Others foresaw much worse to come. In one very explicit expression of the terrible possibilities, artist and political cartoonist Jacob Burck drew the image above, evoking the observation of 19th century German writer Heinrich Heine: “Where one burns books, one will soon burn people.” Newsweek described the events as “’a holocaust of books’… one of the first instances in which the term ‘holocaust’ (an ancient Greek word meaning a burnt offering to a deity) was used in connection with the Nazis.”

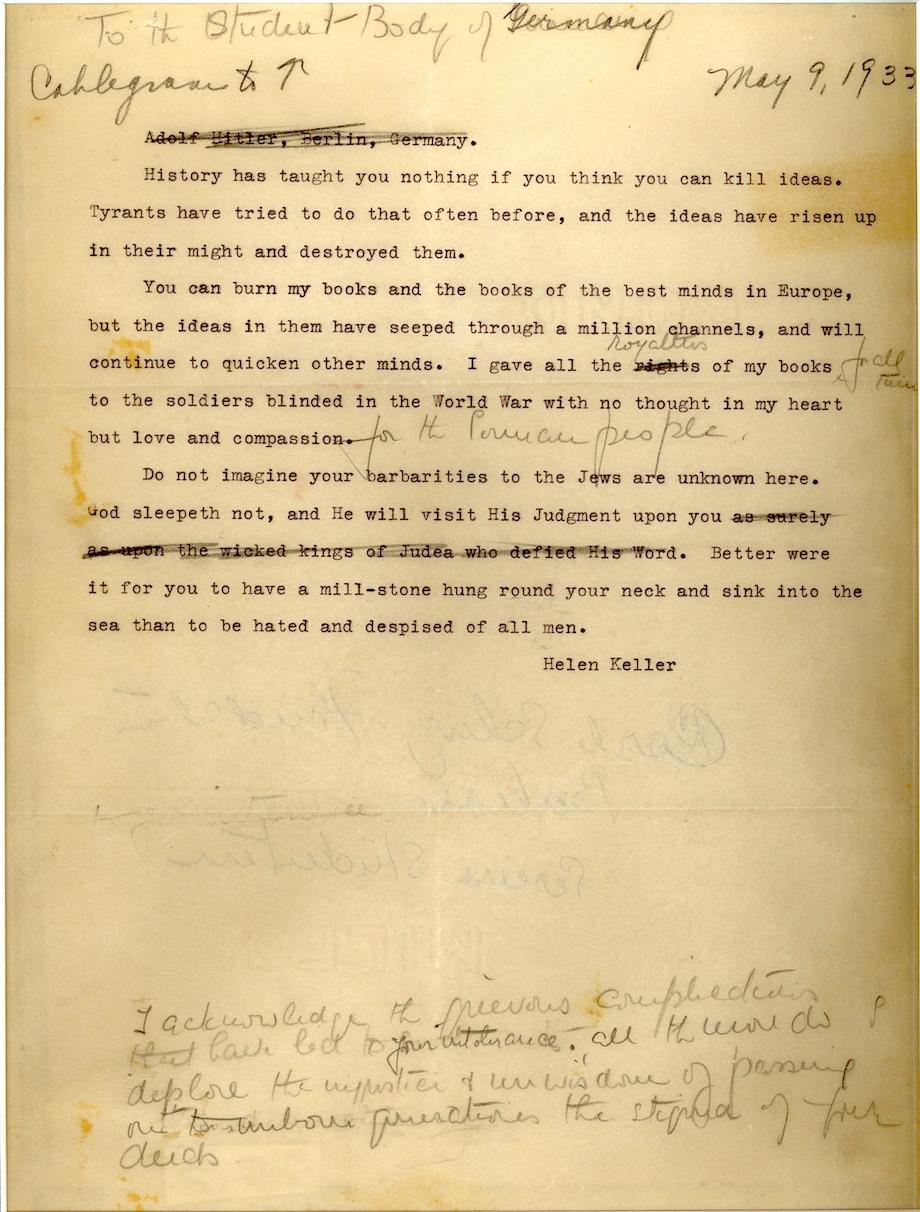

The day before the burnings, Keller also displayed a keen sense for the gravity of book burnings, as well as a “notable… early concern,” notes Rebecca Onion at Slate—outside the Jewish community, that is—for what she called the “barbarities to the Jews.” On May 9, 1933, Keller published a short but pointed open letter to the Nazi students in The New York Times and elsewhere, abjuring them to stop the proposed burnings. She wrote in a religious idiom, invoking the “judgment” of God and paraphrasing the Bible. (Not a traditional Christian, she belonged to a mystical sect called Swedenborgianism.) At the top of the post, you can see the typescript of her letter, with corrections and annotations by Polly Thompson, one of her primary aides. Read the full transcript below:

To the student body of Germany:

History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas. Tyrants have tried to do that often before, and the ideas have risen up in their might and destroyed them.

You can burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe, but the ideas in them have seeped through a million channels and will continue to quicken other minds. I gave all the royalties of my books for all time to the German soldiers blinded in the World War with no thought in my heart but love and compassion for the German people.

I acknowledge the grievous complications that have led to your intolerance; all the more do I deplore the injustice and unwisdom of passing on to unborn generations the stigma of your deeds.

Do not imagine that your barbarities to the Jews are unknown here. God sleepeth not, and He will visit His judgment upon you. Better were it for you to have a mill-stone hung around your neck and sink into the sea than to be hated and despised of all men.

Keller added the penultimate paragraph of the published text later. (See the handwritten addition at the bottom of the typed draft.) Her concern for the “grievous complications” of the German people was certainly genuine. The expression also seems like a targeted rhetorical move for a student audience, conceding the situation as “complex,” and appealing in more philosophical language to “justice” and “wisdom.” The Nazis ignored her protest, as they did the “massive street demonstrations” that took place on the 10th “in dozens of American cities,” the Holocaust Museum writes, “skillfully organized by the American Jewish Congress” and sparking “the largest demonstration in New York City history up to that date.”

Five years later, however, another planned book burning—this time in Austria before its annexation—was prevented by students at Williams College, Yale, and other universities in the U.S., where pro- and anti-Nazi partisans fought each other on several American campuses. U.S. students were able to push the Austrian National Library to lock the books away rather than burn them. Keller “is not known to have commented specifically” on these student protests, writes Medoff, “but one may assume she was deeply proud that at a time when too many Americans did not want to be bothered with Europe’s problems, these young men and women understood the message of her 1933 letter—that the principles under attack by the Nazis were something that should matter to all mankind.”

Note: This post originally appeared on our site in 2017.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content

The 850 Books a Texas Lawmaker Wants to Ban Because They Could Make Students Feel Uncomfortable

America’s First Banned Book: Discover the 1637 Book That Mocked the Puritans

Leave a Reply