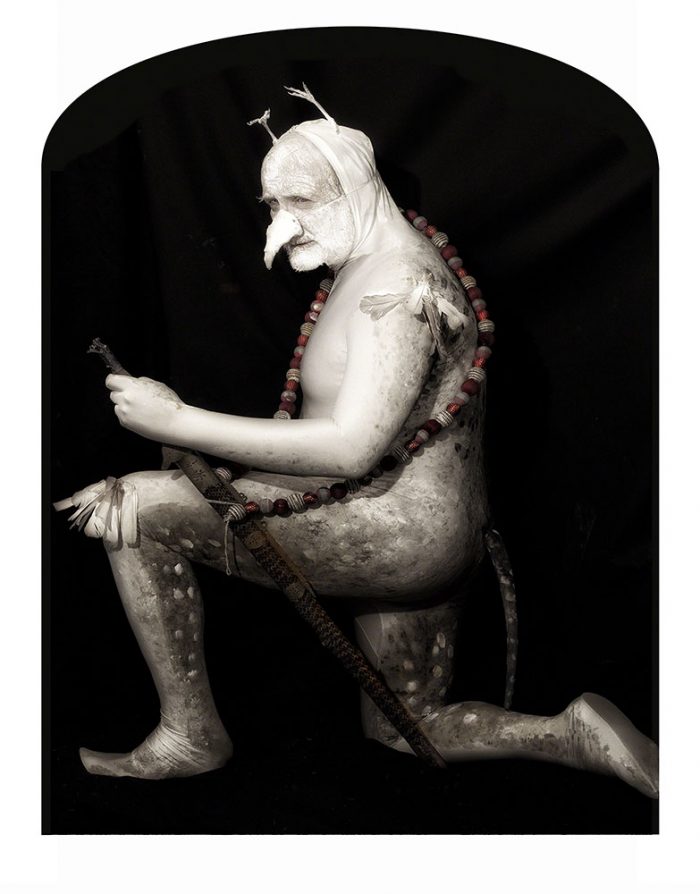

Some moments in history strike us as dramatic ruptures. Certainties are superseded, thrown into chaos by a seismic event, and we find ourselves adrift and anxious. What are artists to do? Gripped by the same fears as everyone else, the same sense of urgency, writers, musicians, filmmakers, painters, etc. may find themselves unable to “breathe with unconditional breath / the unconditioned air,” as Wendell Berry once described the creative process.

We might remember the radical break with tradition when the shocking carnage of World War I sent poets and painters into frightening places they had previously left unexplored. Virginia Woolf summed up the situation in her essay The Leaning Tower: “suddenly like a chasm in a smooth road, the [Great] war came.” Shattered as they were, her generation overcame their paralysis. Modernists of the early 20th century were able to speak to their broken age in ways that continue to speak to ours.

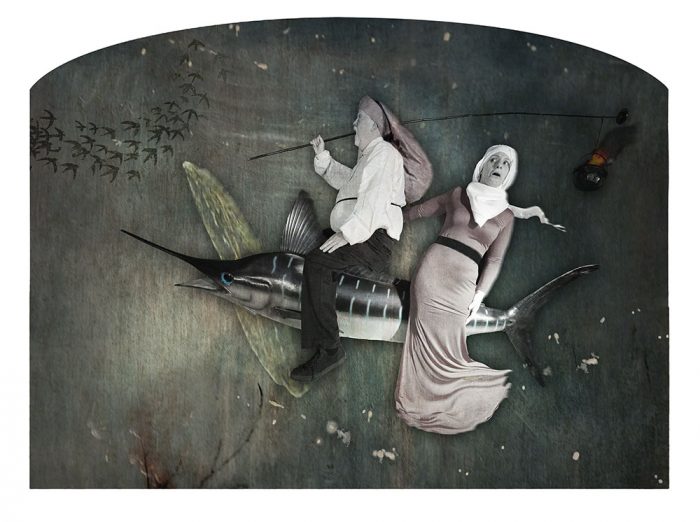

But we should temper our belief that bad times make good art by noting that the most visionary creative minds are not simply reactive, responding to tragedy like reporters on a crime scene. As Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock— two of the 20th century’s most consistently innovative musicians—suggest, artists at all times need a set of guiding principles. (See the two play “Memory of Enchantment” above in 2002.) There is always a lot of personal work to do. And in “turbulent and unpredictable times,” the two jazz greats advise, “the answer to peace is simple; it begins with you.”

A platitude, perhaps, but one they illustrated nearly a year ago in an open letter at Nest HQ with some profound, if challenging, prescriptions for our present cultural illnesses. Shorter and Hancock’s counsel is not a reaction to the rupture of the presidential election, but a response to the events that preceded it, “the horror at the Bataclan… the upheaval in Syria and the senseless bloodshed in San Bernardino.” Not passively waiting to find out where the past few years’ violence and unrest would lead, the two have made ethical, philosophical, and spiritual interventions, presenting their philosophy and ethics through jazz, Buddhism, science, art, and literature.

Below, you can read their ten pieces of advice “to the next generation of artists,” or at least excerpts thereof. They begin with a reassuring preface: “As an artist, creator and dreamer of this world, we ask you not to be discouraged by what you see but to use your own lives, and by extension your art, as vehicles for the construction of peace…. You matter, your actions matter, your art matters.” That said, they also want to assure readers that “these thoughts transcend professional boundaries and apply to all people, regardless of profession.”

First, awaken to your humanity

You cannot hide behind a profession or instrument; you have to be human. Focus your energy on becoming the best human you can be. Focus on developing empathy and compassion. Through the process you’ll tap into a wealth of inspiration rooted in the complexity and curiosity of what it means to simply exist on this planet.

Embrace and conquer the road less traveled

Don’t allow yourself to be hijacked by common rhetoric, or false beliefs and illusions about how life should be lived. It’s up to you to be the pioneers.

Welcome to the Unknown

Every relationship, obstacle, interaction, etc. is a rehearsal for the next adventure in life. Everything is connected. Everything builds. Nothing is ever wasted. This type of thinking requires courage. Be courageous and do not lose your sense of exhilaration and reverence for this wonderful world around you.

Understand the True Nature of Obstacles

We have this idea of failure, but it’s not real; it’s an illusion. There is no such thing as failure. What you perceive as failure is really a new opportunity, a new hand of cards, or a new canvas to create upon.

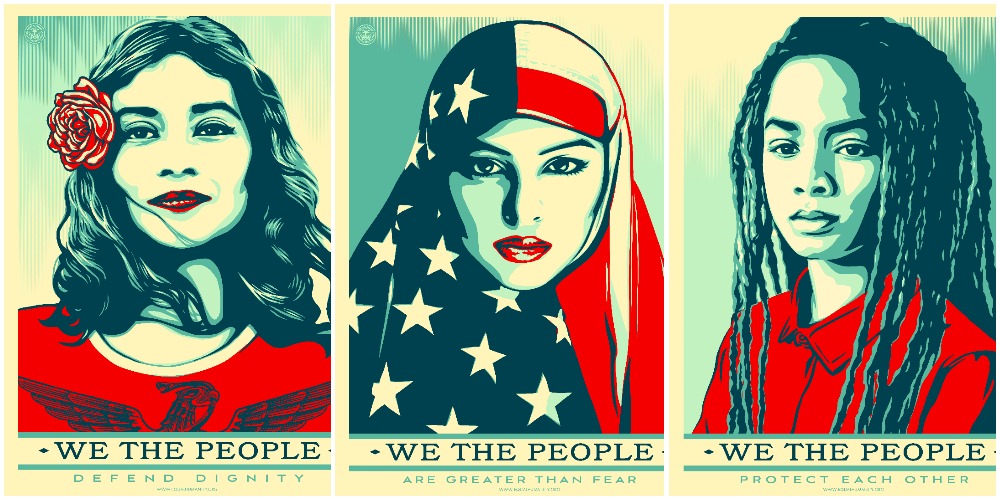

Don’t Be Afraid to Interact with Those Who Are Different from You

The world needs more one-on-one interaction among people of diverse origins with a greater emphasis on art, culture and education. Our differences are what we have in common…. We need to be connecting with one another, learning about one another, and experiencing life with one another. We can never have peace if we cannot understand the pain in each other’s hearts.

Strive to Create Agenda-Free Dialogue

Art in any form is a medium for dialogue, which is a powerful tool… we’re talking about reflecting and challenging the fears, which prevent us from discovering our unlimited access to the courage inherent in us all.

Be Wary of Ego

Creativity cannot flow when only the ego is served.

Work Towards a Business without Borders

The medical field has an organization called Doctors Without Borders. This lofty effort can serve as a model for transcending the limitations and strategies of old business formulas which are designed to perpetuate old systems in the guise of new ones.

Appreciate the Generation that Walked Before You

Your elders can help you. They are a source of wealth in the form of wisdom…. Don’t waste time repeating their mistakes.

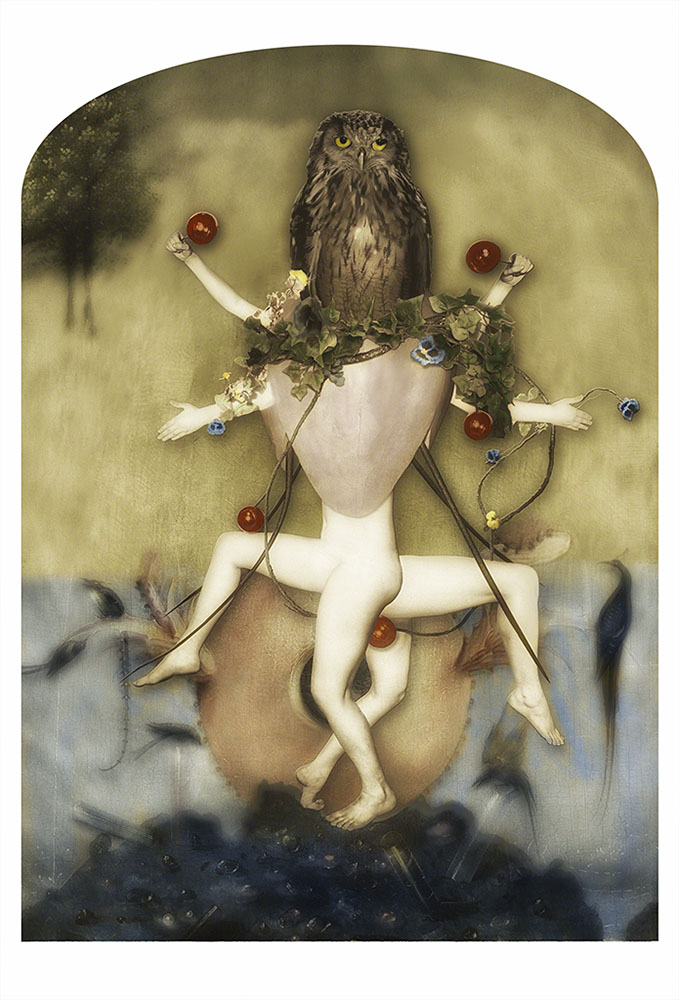

Lastly, We Hope that You Live in a State of Constant Wonder

As we accumulate years, parts of our imagination tend to dull. Whether from sadness, prolonged struggle, or social conditioning, somewhere along the way people forget how to tap into the inherent magic that exists within our minds. Don’t let that part of your imagination fade away.

Whether you’re a jazz fan, musician, artist, writer, accountant, cashier, trucker, teacher, or whatever, I can’t think of a wiser set of guidelines with which to confront the suffocating epidemic of cynicism, delusional thinking, rampant bigotry, hatred, and self-absorption of our time. Read Shorter and Hancock’s full open letter at Nest HQ.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness