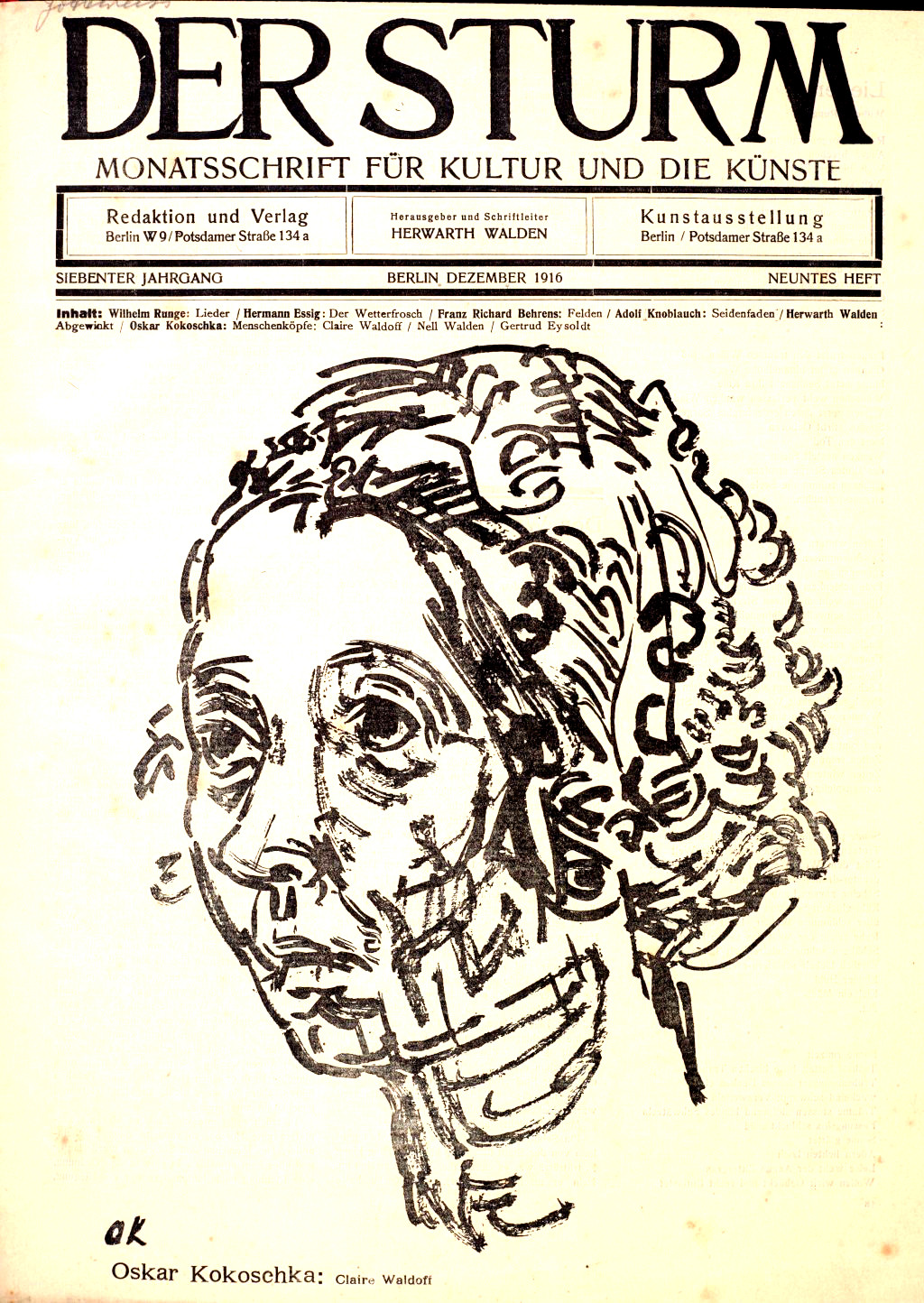

As I recall, if you asked men in the 1990s to describe ideal the woman, a great many would have made references to Uma Thurman, who spent that decade playing high-profile roles in acclaimed movies like Pulp Fiction and Gattaca—as well as less-acclaimed movies like The Avengers and Batman & Robin (but hey, you can’t pick winners all the time). But animator, director, American Monty Python member and all-around visionary Terry Gilliam made use of the powerful appeal of Thurman’s presence even earlier, when—making The Adventures of Baron Munchausen—-he needed just the right young lady for a scene recreating Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance painting The Birth of Venus.

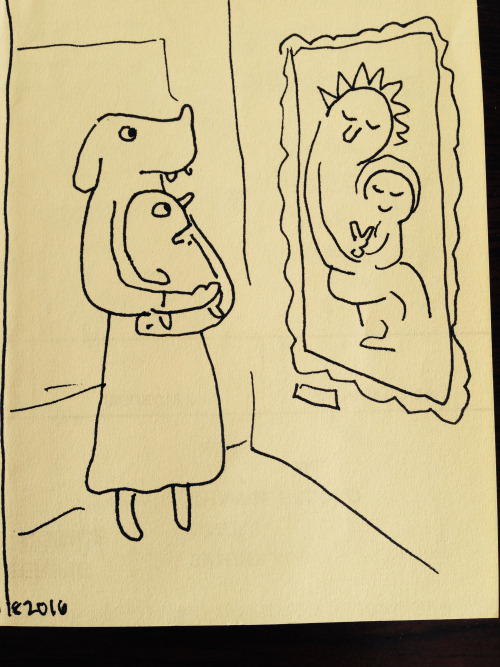

“The casting director in L.A. said, ‘You’ve got to meet this girl,’ ” Gilliam remembers in the clip from this year’s BBC Arts documentary Botticelli’s Venus: The Making on an Icon at the top of the post. “There she was: statuesque, beautiful, intelligent—incredibly intelligent.” He compares the original canvas itself to a “widescreen cinema,” as well as, just as aptly, to a lower art form entirely: “The winds are blowing, her hair starts billowing out, the dressing girl is bringing in the robe — it’s a really funny painting, looking at it again, because she’s there, static, elegant, naked, sexy. The robe wouldn’t look so good if the winds weren’t blowing, nor would her hair look so beautiful. It’s like, this is a commercial for shampoo!”

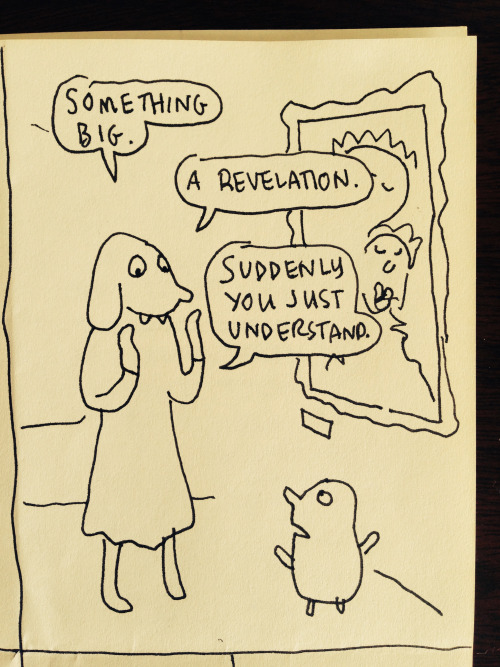

As Monty Python fans all know, Gilliam had worked with The Birth of Venus before, using his signature cutout animation technique, which defined much of the look and feel of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, to make Venus dance. “I like testing how much I like something, or how beautiful something is, by making fun of it,” he says to his BBC interviewer. “If it withstands my silliness, it’s really great art.” Further props to Botticelli come at the end of the clip, when she asks Gilliam if he thinks Venus represents “the ultimate male fantasy.” “Oh, why not?” he immediately replies. “You don’t do much better than that. I think he really cracked that one.”

Related Content:

Botticelli’s 92 Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Terry Gilliam Reveals the Secrets of Monty Python Animations: A 1974 How-To Guide

Terry Gilliam’s Debut Animated Film, Storytime

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.