What would you choose for your last meal?

The comfort food of your childhood?

Or some lavish dish you never had a chance to taste?

What might your choice reveal about your race, regional origins, or economic circumstances?

Artist Julie Green developed a fascination with death row inmates’ final meals while teaching in Oklahoma, where the per capita execution rate exceeds Texas’ and condemned prisoners’ special menu requests are a matter of public record:

Fried fish fillets with red cocktail sauce from Long John Silver’s

Large pepperoni pizza with sausage and extra mushrooms and a large grape soda.

The latter order, from April 29, 2014, was denied on the grounds that it would have exceeded the $15-per-customer max. The prisoner who’d made the request skipped his last meal in protest.

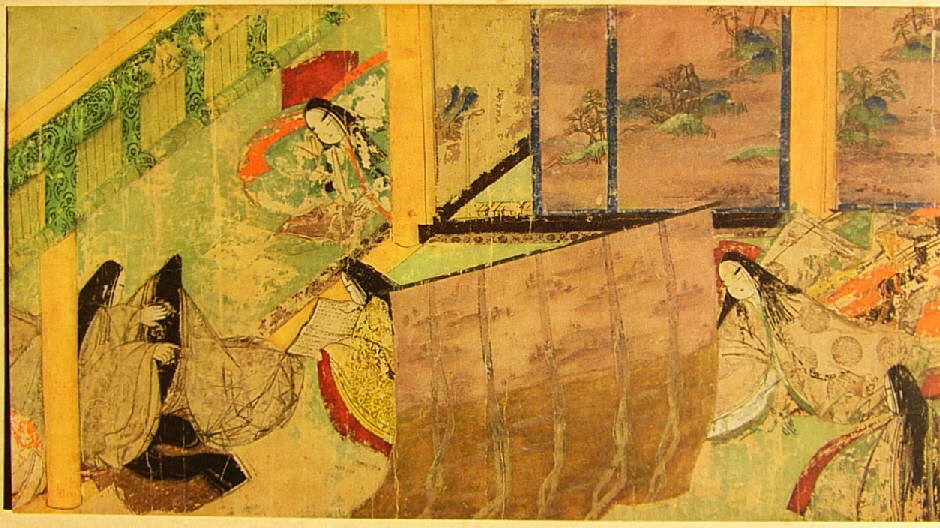

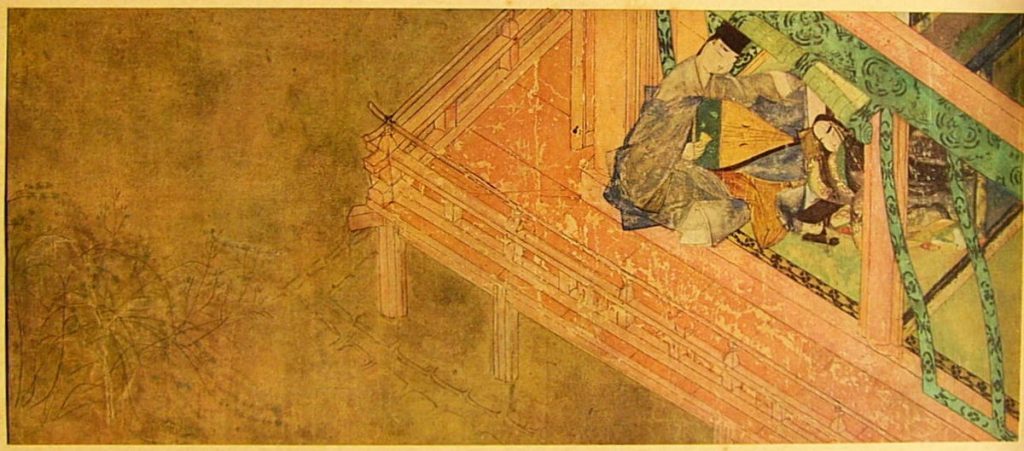

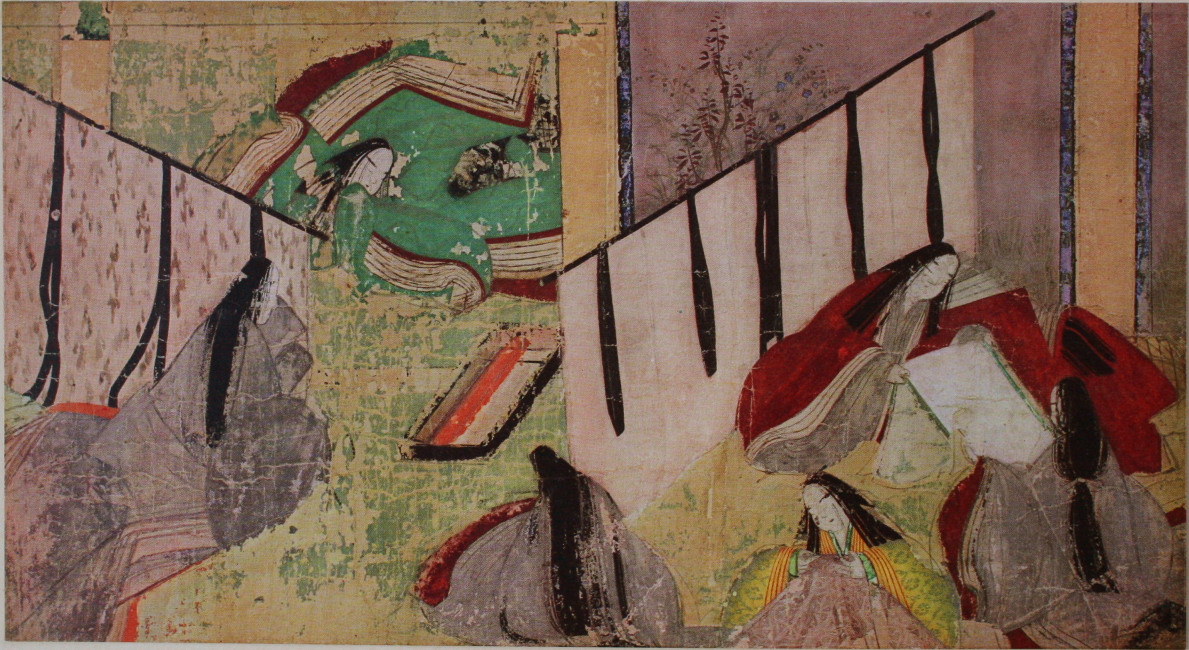

Green recreates these, and hundreds of other death row prisoners’ last suppers in cobalt blue mineral paint on carefully selected second-hand plates. The influence of Dutch Delftware and Spanish still life painting are evident in her depiction of burgers, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and pie.

Many of the requests betray a childlike poignancy:

A single honey bun (North Carolina, January 30, 1998)

Shrimp and ice cream (New Mexico, November 6, 2001)

A peanut butter and jelly sandwich (Florida, February 26, 2014)

One man got permission for his mother to prepare his last meal in the prison kitchen. Another was surprised with a birthday cake after prison staff learned he had never had one before.

Some refrain from exercising their right to a special request, a choice Green documents in text. She resorts to similar tactics when a prisoner requests that his final meal be kept confidential.

Each meal Green paints is accompanied by a menu, the date, and the state in which it was served, but the prisoners and their crimes go unnamed. She has committed to producing fifty plates a year until capital punishment is abolished.

Green narrates a Last Supper slideshow above, or you can browse all the plates in the project, organized by state here.

Related Content:

What Prisoners Ate at Alcatraz in 1946: A Vintage Prison Menu

The Odd Collection of Books in the Guantanamo Prison Library

Modern Art Was Used As a Torture Technique in Prison Cells During the Spanish Civil War

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday