When Paulo Coelho’s novel The Alchemist came out in English, the level of popularity it eventually attained seriously impressed me. Then I went to Latin America, where the Spanish version seemed to have won a vaster readership still. I haven’t yet gone to Brazil to gauge the book’s popularity on the streets of Coelho’s homeland since its first publication to relatively little interest, but it surely hasn’t gone unknown there. As many fans as The Alchemist has, though, the inspiration-and-destiny-inflected appeal of the text entirely escapes some readers, in whichever language they read it. Perhaps they’d prefer an edition illustrated by Mœbius?

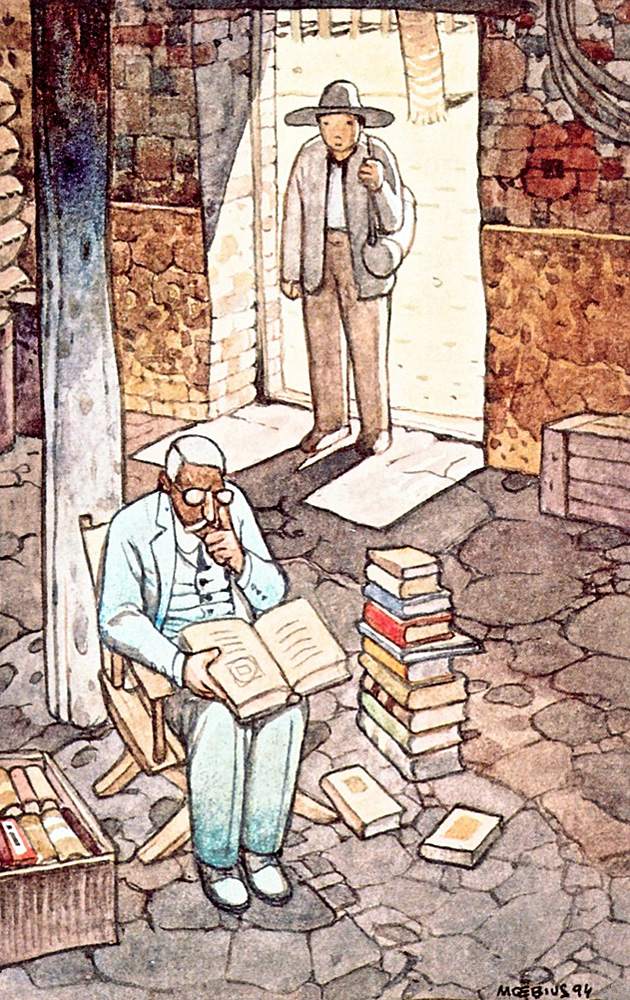

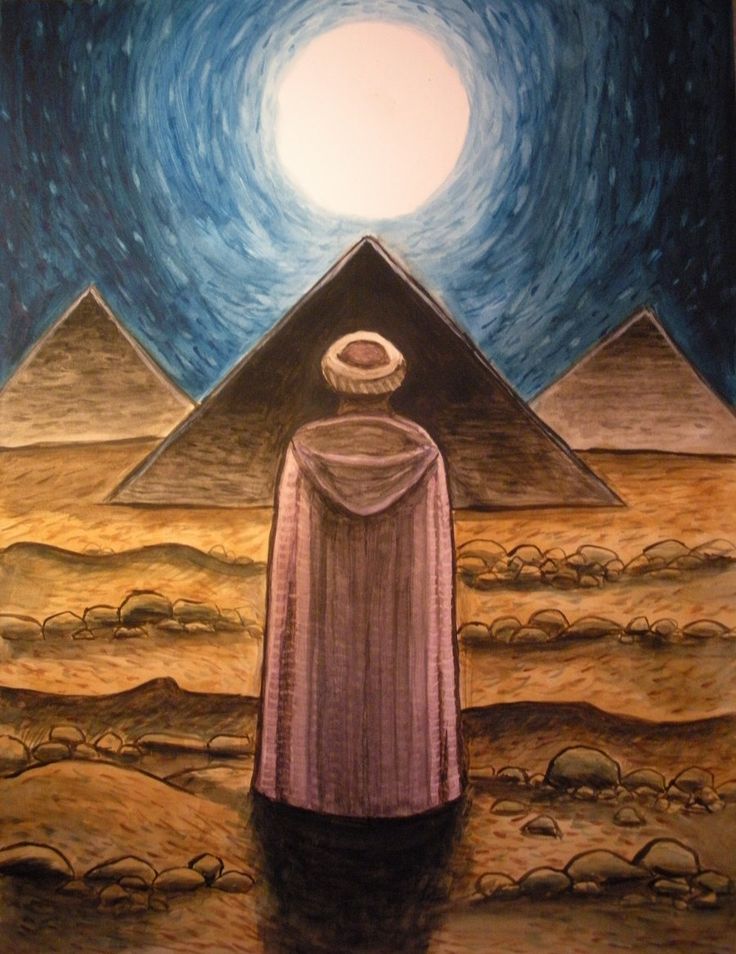

Born Jean Giraud, Mœbius’ career guarantees him a permanent place as one of the most influential comic artists ever to live. Even apart from the achievements in the medium in which he became famous — his founding work on Heavy Metal, his creation of nontraditional western outlaw Blueberry — he did a good deal of work that brought his singularly imaginative aesthetic into other creative realms, such as concept art from Alejandro Jodorowky’s Dune and illustrations for Dante’s Paradiso. In some sense, it might have seemed natural for him to lend his hand to Coelho’s fantasy tale of an Andalusian shepherd boy on a treasure-hunting journey to Egypt.

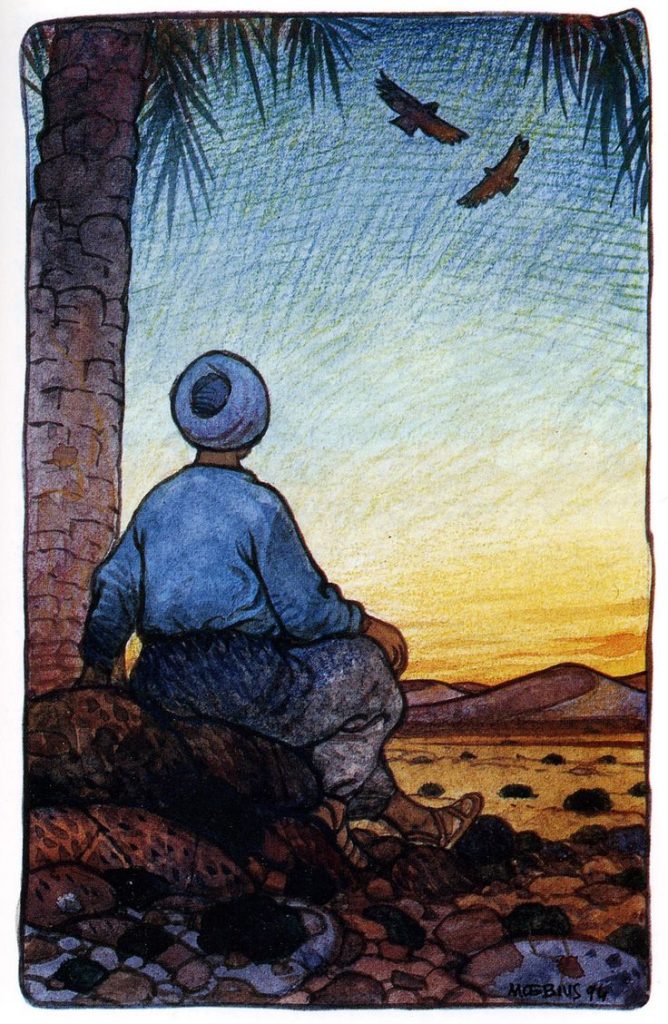

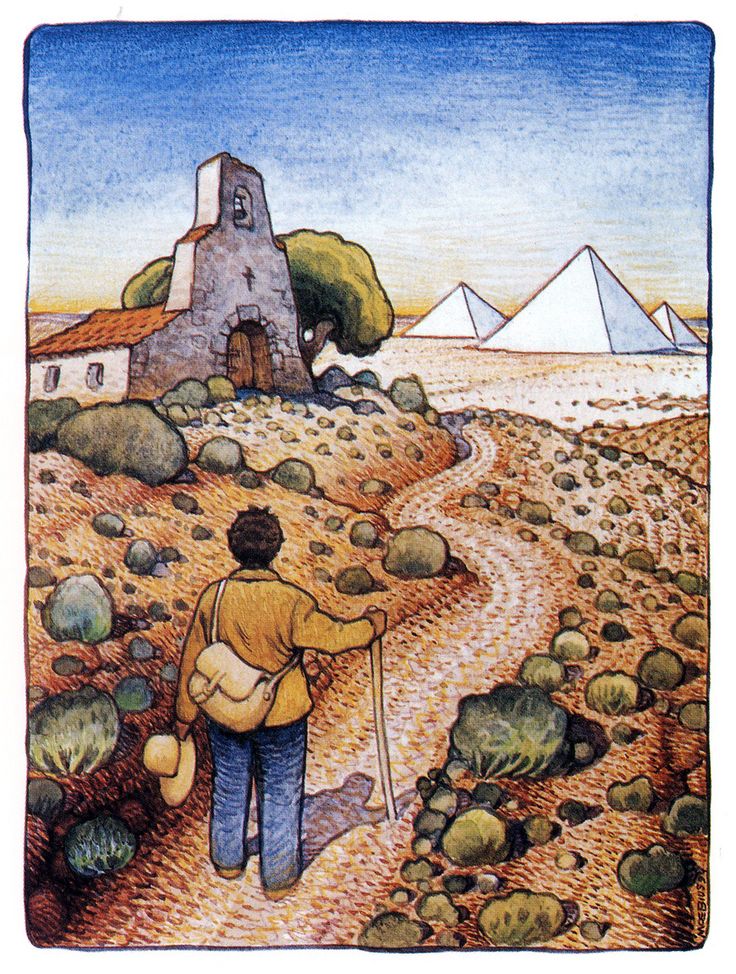

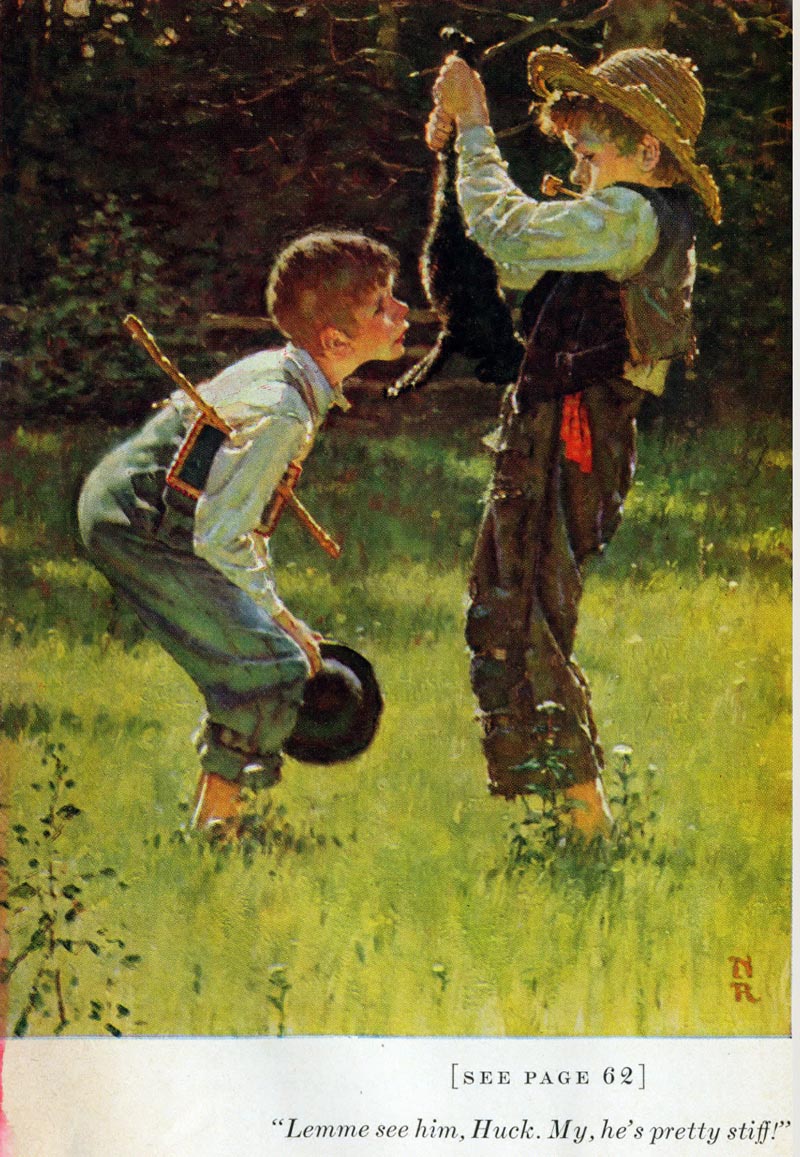

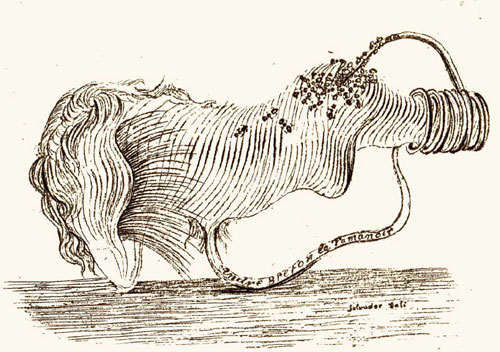

The Illustrated Alchemist: A Fable About Following Your Dream came out in 1998, and it included 35 Mœbius illustrations, four of which you see here. The artist’s signature style, which he usually used in the service of dark, complex fusions of past and present, might at first sound ill-suited for Coelho’s simple fable, but Mœbius adapts well to the material. Even if you put down the book unconvinced by Coelho’s arguments about following your dream, you might consider looking to Mœbius instead with our post on his tips for aspiring artists. Either way, The Illustrated Alchemist itself showcases a collaboration between two well-known creators who most definitely paid their dues.

Related content:

How Paulo Coelho Started Pirating His Own Books (And Where You Can Find Them)

Paulo Coelho on the Fear of Failure

The Inscrutable Imagination of the Late Comic Artist Mœbius

Mœbius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

Mœbius Illustrates Dante’s Paradiso

Moebius Gives 18 Wisdom-Filled Tips to Aspiring Artists (1996)

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.