All artists are mortal. Lucian Freud was, by anyone’s definition, an artist. Therefore, Lucian Freud was mortal — as, so his artistic vision emphasized, are the subjects of his “stark and revealing paintings of friends and intimates, splayed nude in his studio,” which, wrote William Grimes in Freud’s 2011 New York Times obituary, “recast the art of portraiture and offered a new approach to figurative art.” Freud “put the pictorial language of traditional European painting in the service of an anti-romantic, confrontational style of portraiture that stripped bare the sitter’s social facade. Ordinary people — many of them his friends — stared wide-eyed from the canvas, vulnerable to the artist’s ruthless inspection.”

Or, in Freud’s own words: “I work from the people that interest me and that I care about, in rooms that I live in and know.” Just as every mortal artist’s career must begin with a first work, so it must end with a final work, and in the clip at the top of the post you can witness a few minutes from the very last day the painter spent painting somebody who interested him and whom he cared about, in a room he lived in and knew. He spent it on this canvas, an enormous and unfinished portrait of his assistant David Dawson and his whippet Eli called Portrait of the Hound.

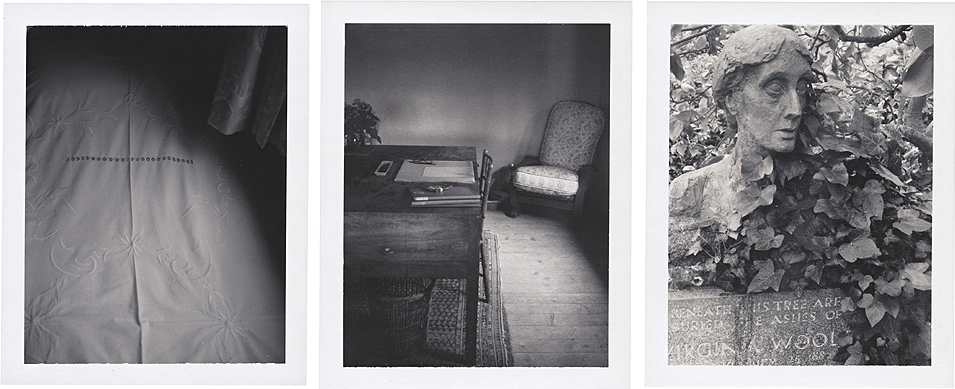

“Every morning, seven days a week, I sat for Lucian,” said Dawson to The Telegraph’s Martin Gayford. “There was a very open acceptance of his not having so long to live. But he still had a burning desire to make a very good painting, right up to the end. He was painting three weeks before he died.” Dawson shot this footage of Freud’s final working day, July 3, 2011, which made it into the documentary Lucian Freud: Painted Life [part one, part two]. “We are in Freud’s home, which is very quiet, with lots of paintings on the walls, and filled with a subtle, natural light,” writes Hyperallergic’s Elisa Wouk Almino. “He was particular about painting under a northern light, which he once described as ‘cold and clear and constant.’ ”

Whether Freud lived the last truly painterly life, we can’t know for sure; we do know, however, that he lived one of the most resolutely painterly lives in recent history. “Lucian didn’t bother about what he didn’t need to,” said his final subject. “What was important was trying to make the best painting he possibly could. Work was what kept him going: that need to get out of bed, pick up a paintbrush and make another mark, make another decision. So that was what he did. It was a good way to go about living a life.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Jackson Pollock 51: Short Film Captures the Painter Creating Abstract Expressionist Art

Astonishing Film of Arthritic Impressionist Painter, Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1915)

Watch Picasso Create Entire Paintings in Magnificent Time-Lapse Film (1956)

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.