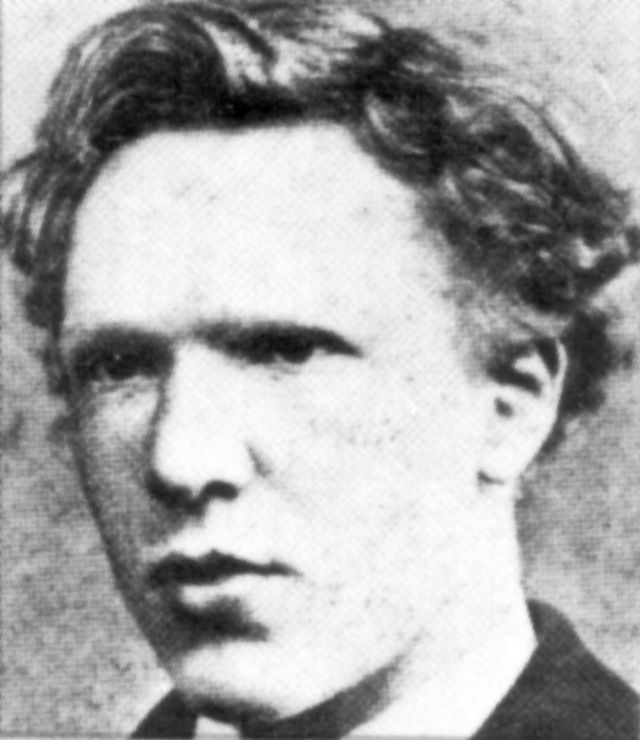

Close your eyes for a moment and picture the artist Vincent Van Gogh. What do you see?

Probably one of the prolific post-Impressionist’s self-portraits. That’s all well and good, but who else did you see?

Indie darling (and Incredible Hulk adversary) Tim Roth?

Director Martin Scorsese?

Thanks to the recently discovered photograph at the top of this article, we may soon have the option of picturing the actual Vincent Van Gogh as an adult artist. As Petapixel tells us, he sat for portraits at age 13, and again as a 19-year-old gallery apprentice (below), but beyond that no photographic evidence of the camera-shy artist was known to exist.

Exciting!

That’s Paul Gauguin on the far right. Others at the table include Emile Bernard and Arnold Koning, politician Felix Duval and actor-director André Antoine. But who is the bearded man smoking the pipe?

Van Gogh?

So thought the two collectors who purchased the small 1887 photo at a house sale a couple of years ago. Serge Plantureux, an antiquarian bookseller and photography expert who examined their find was optimistic enough to help them with further research, as he noted in the French magazine, L’Oeil de la Photographie:

I didn’t want to start doing what Americans call “wishful thinking,” that trap into which collectors and researchers fall, where their reasoning is governed only by what they want to see.

Don’t ditch Douglas, Roth, and Scorsese just yet, however. Experts at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum say the bearded fellow cannot be the artist. According to them, there’s not even much of a resemblance. He wasn’t so much camera shy, as deadly opposed to the photographic medium. His refusal to be photographed was an act of resistance.

That kind of puts a damper on things…

So.. no go Van Gogh? Oh well…vive la photo nouvellement découverte de Paul Gauguin (and friends)!

Related Content:

The Unexpected Math Behind Van Gogh’s “Starry Night”

Simon Schama Presents Van Gogh and the Beginning of Modern Art

Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’ Re-Created by Astronomer with 100 Hubble Space Telescope Images

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday