René Clair’s 1924 avant-garde masterpiece Entr’Acte opens with a cannon firing into the audience and that’s pretty much a statement of purpose for the whole movie. Clair wanted to shake up the audience, throwing it into a disorienting world of visual bravado and narrative absurdity. You can watch it above.

The film was originally designed to be screened between two acts of Francis Picabia’s 1924 opera Relâche. Picabia reportedly wrote the synopsis for the film on a single sheet of paper while dining at the famous Parisian restaurant Maxim’s and sent it to Clair. While that handwritten note was the genesis of what we see on screen, it’s Clair sheer cinematic inventiveness that is why the film is still shown in film schools today.

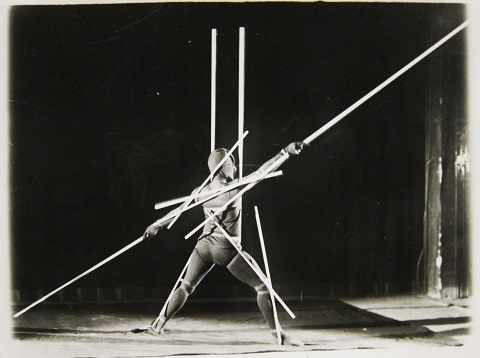

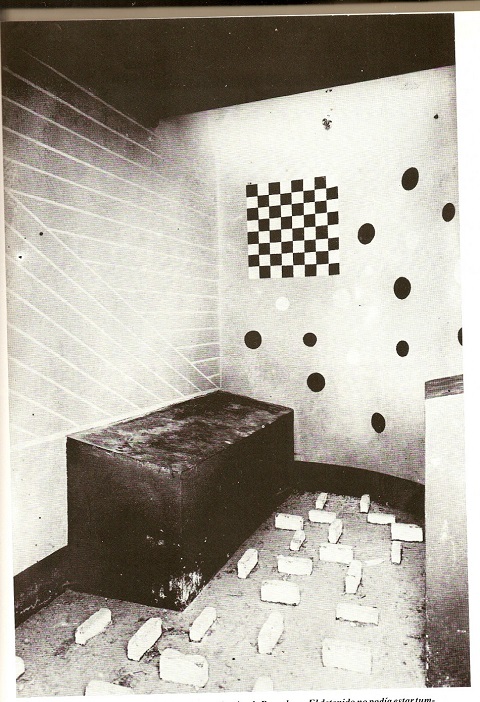

Clair sought to create a work of “pure cinema,” so he filled the film with just about every camera trick in the book: slow motion, fast motion, split screen and superimpositions among others. The camera is unbound and wildly kinetic. At one point, Clair mounts the camera upside down to the front of a rollercoaster.

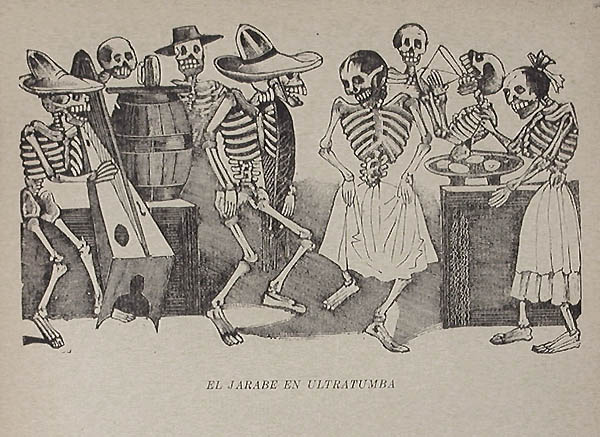

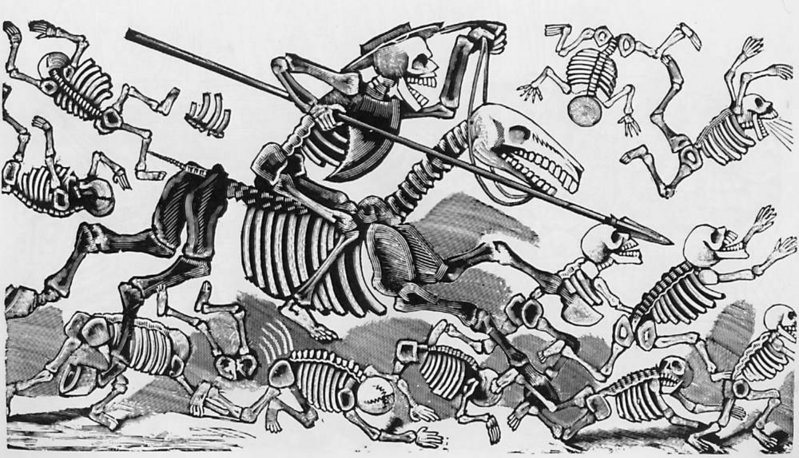

In true Dadaist fashion, Clair creates a series of striking images – an upskirt shot of a leaping ballerina; a funeral procession bounding down the street in slow motion; a corpse springing out of a coffin – that seem to cry out for an explanation but remain maddeningly, frequently hilariously obscure.

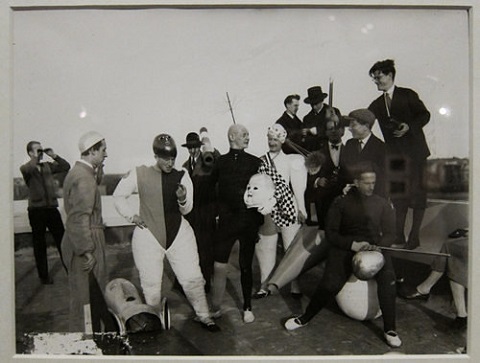

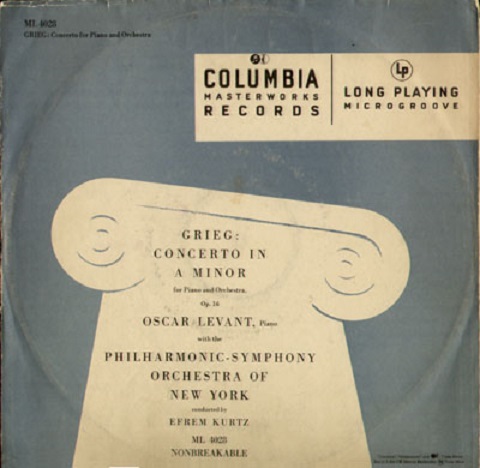

The movie also serves as a class portrait of the Parisian avant-garde scene of the early ‘20s. Picabia and Erik Satie – who scored the movie – are the ones who fired that cannon. In another scene, Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray can be seen playing chess with each other on a Parisian rooftop.

Compared to Luis Bunuel and Salvador Dali’s notorious 1928 short Un Chien Andalou – a movie that is still quite shocking today – Entr’Acte is a much lighter, funnier work, one that looks to thwart bourgeois expectations of narrative logic but doesn’t quite try to shock them into indignant outrage. In fact, to modern eyes, the movie feels at times like a particularly unhinged Monty Python skit. Picabia himself once asserted that Entr’acte “respects nothing except the right to roar with laughter.” So watch, laugh and prepare to be confused.

Entr’Acte will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Related Content:

Two Vintage Films by Salvador Dalí and Luis Buñuel: Un Chien Andalou and L’Age d’Or

The Seashell and the Clergyman: The World’s First Surrealist Film

David Lynch Presents the History of Surrealist Film (1987)

A Tour Inside Salvador Dalí’s Labyrinthine Spanish Home

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.