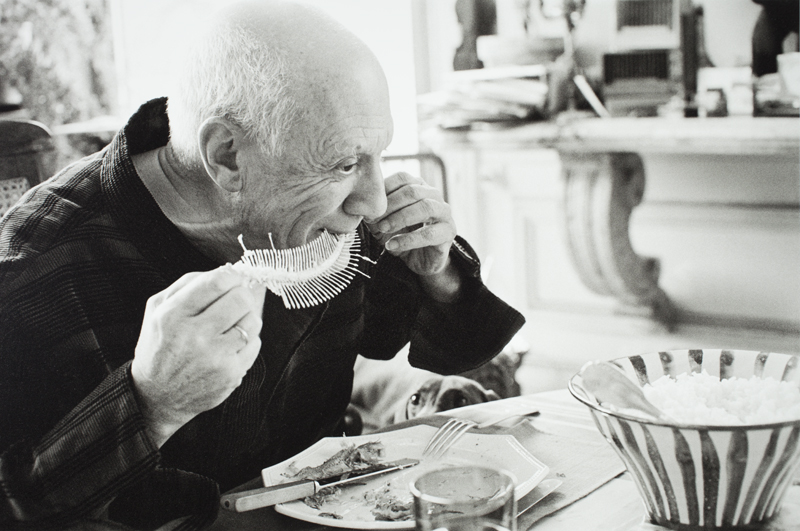

Back in 1964, Pablo Picasso shared with Vogue’s food columnist Ninette Lyon two of his favorite recipes — one for Eel Stew, the other for Omelette Tortilla Niçoise. If you live in the South of France, as Picasso did, the recipes probably won’t be entirely foreign to you. But if you aren’t so lucky, you might want to add these recipes, now reprinted by Vogue, to your culinary bucket list.

Below, we’ve highlighted the ingredients for the recipes. But, for step-by-step directions on how to prepare the dishes, head over to Vogue itself.

For more recipes from cultural icons — Hemingway, Tolstoy, Alice B. Toklas, Jane Austen, David Lynch, Miles Davis, etc. — head to the bottom of this page.

Eel Stew for Four People

6 tablespoons olive oil

6 tablespoons butter

12 small white onions

1 teaspoon sugar

2 yellow onions, chopped

12 mushrooms

⅓ pound salt pork, cubed

2 shallots, minced

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 eels of about 1 pound each, cut into four- to five-inch sections

1 bottle of good red wine

1 tablespoon flour

Salt, pepper, cayenne pepper

Bouquet garni: thyme, bay leaf, parsley, fennel, and a small branch of celery

Omelette Tortilla Niçoise for Four People

6 tablespoons olive oil

1 large onion

4 peppers, red and green

3 tomatoes

2 tablespoons wine vinegar

8 eggs

Salt and pepper

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway’s Favorite Hamburger Recipe

Leo Tolstoy’s Family Recipe for Macaroni and Cheese

David Lynch Teaches You to Cook His Quinoa Recipe in a Weird, Surrealist Video

Thomas Jefferson’s Handwritten Vanilla Ice Cream Recipe

Alice B. Toklas Reads Her Famous Recipe for Hashish Fudge (1963)

Marilyn Monroe’s Handwritten Turkey-and-Stuffing Recipe

Read Filmmaker Luis Buñuel’s Recipe for the Perfect Dry Martini, and Then See Him Make One

Miles Davis’ “South Side Chicago Chili Mack” Recipe Revealed

The Recipes of Iconic Authors: Jane Austen, Sylvia Plath, Roald Dahl, the Marquis de Sade & More