There’s an old truism in Hollywood that a movie shouldn’t last much longer than the endurance of the average audience member’s bladder. Most feature films run around an hour and a half to two hours, though summer blockbusters can last longer. Studios generally resist making long movies for the simple reason that they can’t pack as many screenings per day. While some art house auteurs have made movies that extend to bladder-busting lengths – Bela Tarr’s brilliant Satantango clocks in at seven and a half hours – the place to find truly long movies is in the art world.

Christian Marclay’s masterpiece The Clock is a 24-hour montage of watches, clocks and other timepieces from iconic movies synced to the actual time the film is running. Another incredibly long movie is the aptly named A Cure for Insomnia, which features artist Lee Groban reading a really long poem intercut with clips of porn and heavy metal music. That movie lasts over 3 days. And if you wanted to watch the entirety of Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s movie Beijing 2003 – which documents every single street within Beijing’s inner ring – it would take you over a week.

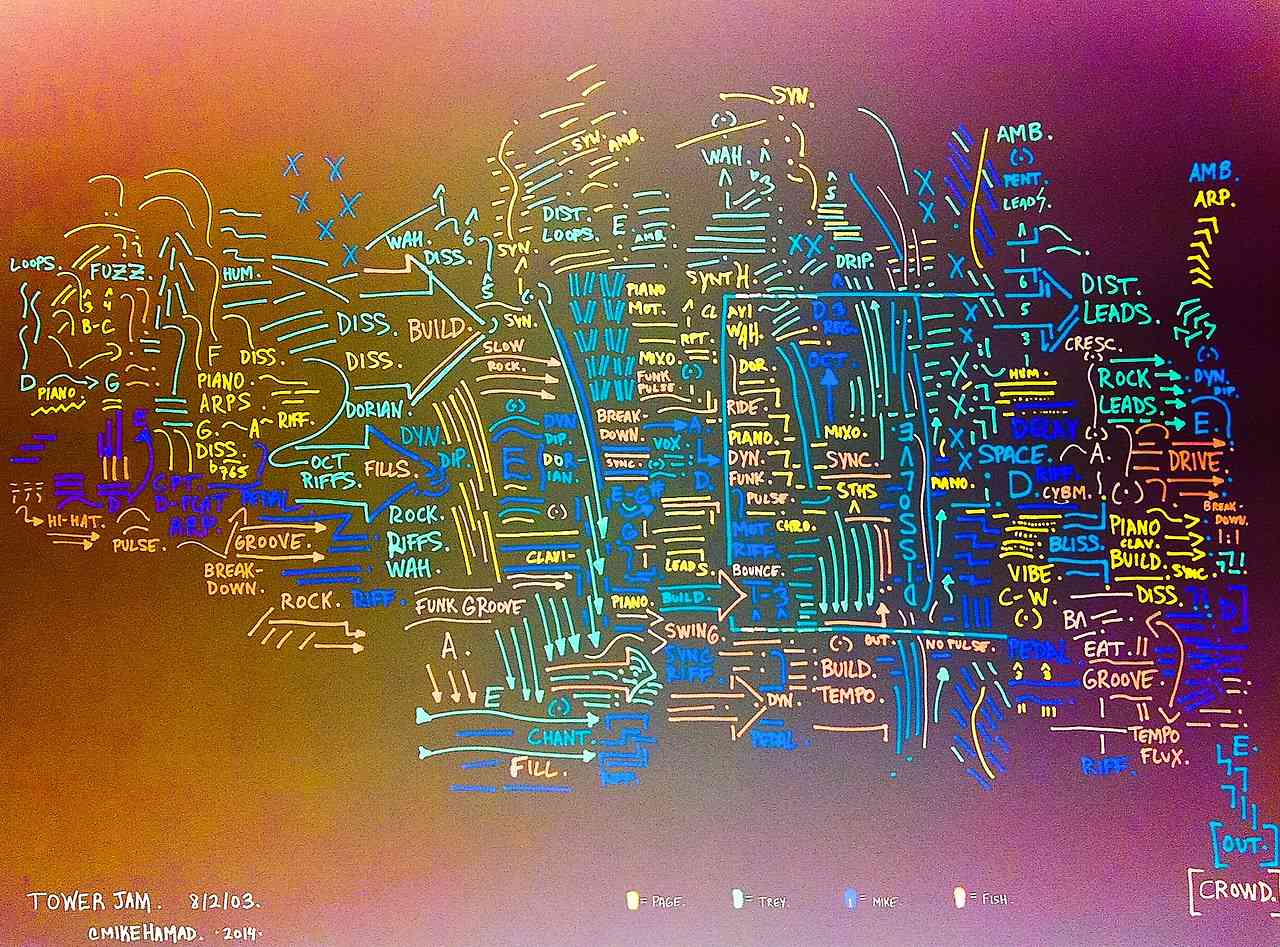

But those films have nothing on Swedish artist and filmmaker Anders Weberg, who is making Ambiancé, which is, at 720 hours, the longest movie in the history of cinema. 720 hours. That’s 30 days. To put this into perspective, you can watch the entire special extended cut of the Lord of the Rings trilogy over 60 times in the time it takes for Ambiancé to unspool just once. The first trailer came out July 4th, and it clocks in at 72 minutes long, making it almost a feature unto itself. You can see it above. If this seems lengthy – most trailers are three or so minutes after all – note that Weberg promises that the next trailer will last seven hours and 20 minutes.

Weberg describes Ambiancé as a movie where space and time intertwine “into a surreal dream-like journey beyond places and [it] is an abstract nonlinear narrative summary of the artist’s time spent with the moving image. A sort of memoir movie.” As you can see above, the movie features densely layered images with a haunting, minimal score. Weberg plans to screen the entirety of the movie in 2020 on every continent simultaneously just once before destroying it. The trailer is only going to be available until July 20th, so watch it while you can.

Related Content:

The Clock, the 24-Hour Montage of Clips from Film & TV History, Introduced by Alain de Botton

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.