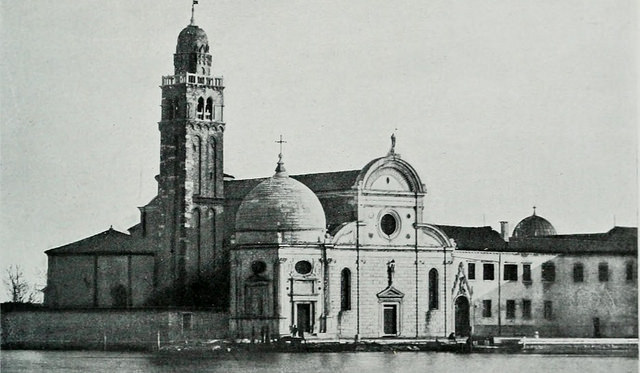

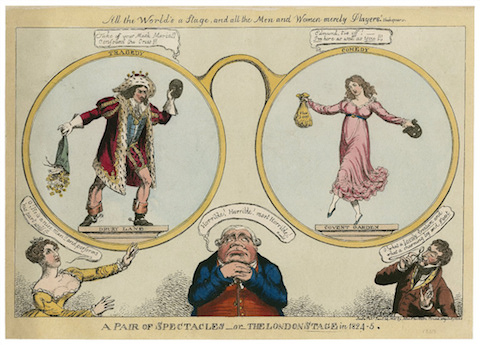

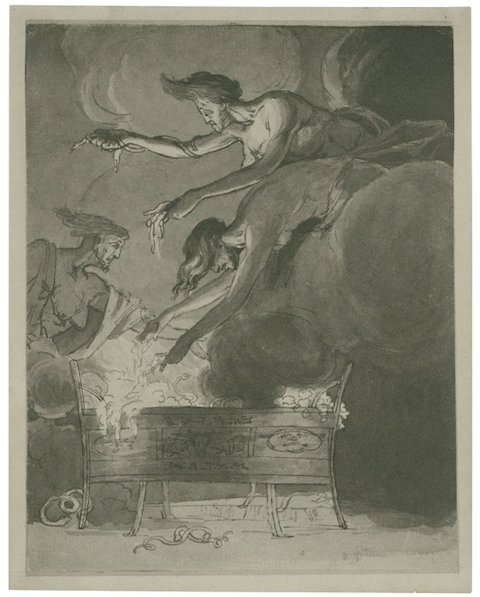

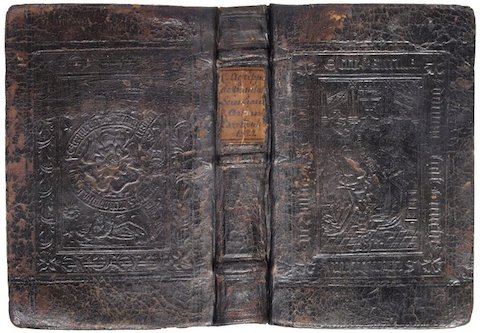

Thanks to Kalev Leetaru, a Yahoo! Fellow in Residence at Georgetown University, you can now head over to a new collection at Flickr and search through an archive of 2.6 million public domain images, all extracted from books, magazines and newspapers published over a 500 year period. Eventually this archive will grow to 14.6 million images.

This new Flickr archive accomplishes something quite important. While other projects (e.g., Google Books) have digitized books and focused on text — on printed words — this project concentrates on images. Leetaru told the BBC, “For all these years all the libraries have been digitizing their books, but they have been putting them up as PDFs or text searchable works.” “They have been focusing on the books as a collection of words. This inverts that.”

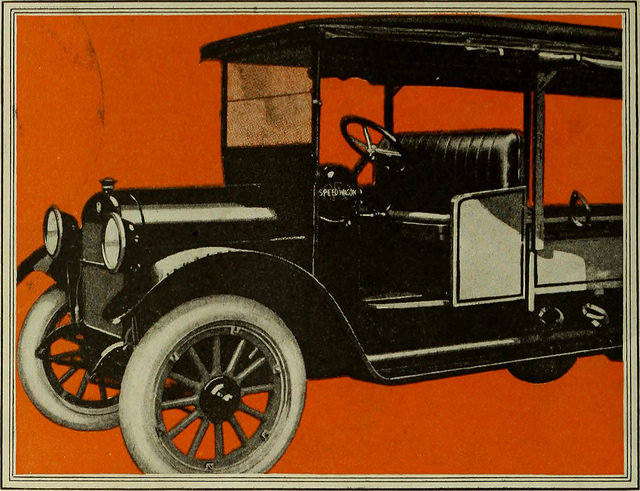

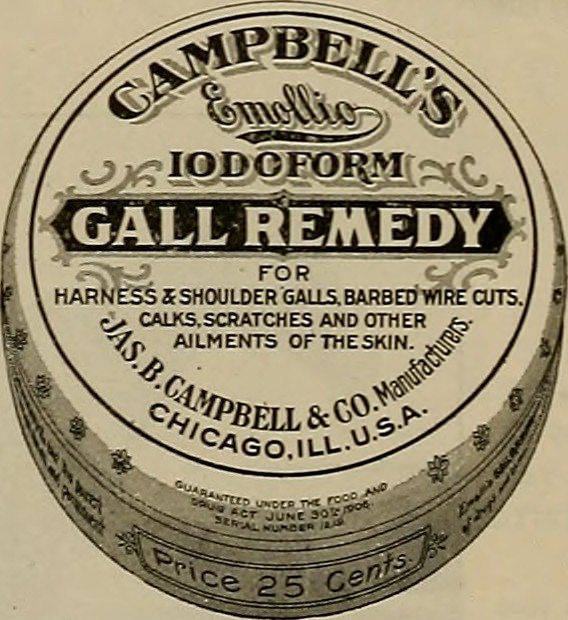

The Flickr project draws on 600 million pages that were originally scanned by the Internet Archive. And it uses special software to extract images from those pages, plus the text that surrounds the images. I arrived at the image above when I searched for “automobile.” The page associated with the image tells me that the image comes from an old edition of the iconic American newspaper, The Saturday Evening Post. A related link puts the image in context, allowing me to see that we’re dealing with a 1920 ad for an REO Speedwagon. Now you know the origin of the band’s name!

I should probably add a note about how to search through the archive, because it’s not entirely obvious. From the home page of the archive, you can do a keyword search. As you’re filling in the keyword, Flickr will autopopulate the box with the words “Internet Archive Book Images’ Photostream.” Make sure you click on those autopopulated words, or else your search results will include images from other parts of Flickr.

Or here’s an easier approach: simply go to this interior page and conduct a search. It should yield results from the book image archive, and nothing more.

In case you’re wondering, all images can be downloaded for free. They’re all public domain.

More information about the new Flickr project can be found at the Internet Archive.

In the relateds below, you can find other great image archives that recently went online.

via the BBC and Peter Kaufman

Related Content:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

New York Public Library Puts 20,000 Hi-Res Maps Online & Makes Them Free to Download and Use

The Rijksmuseum Puts 125,000 Dutch Masterpieces Online, and Lets You Remix Its Art