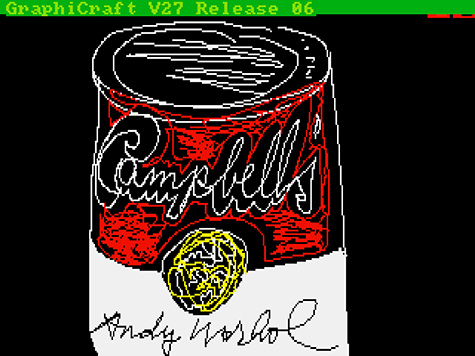

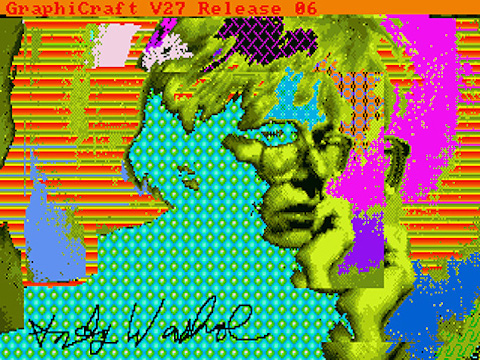

If you saw our post on Andy Warhol digitally painting Debbie Harry at the 1985 launch of the Commodore Amiga 1000, you know how effusively — effusively by the impassive Warholian standard, anyway — the artist praised the computer’s artistic power. Now, thanks to a recent discovery by members of Carnegie Mellon University’s Computer Club, we know for sure that the mastermind behind the Factory didn’t simply shill for Commodore; he actually spent time creating work with their then-graphically advanced machine, a few pieces of which, unseen for nearly thirty years, just came back to light on monitors everywhere. Above we have the 1985 self-portrait Andy2. The 27 other finds include a mouse-drawn rendition of his signature Campbell’s soup can and a three-eyed Venus, surely one of the eerier early uses of cut-and-paste functionality, all products, explains the press release from The Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie Mellon,” of a commission by Commodore International to demonstrate the graphic arts capabilities of the Amiga 1000 personal computer.”

1980s electronics-loving artist Cory Arcangel, upon watching the video of Warhol at the launch, contacted the Andy Warhol Museum “regarding the possibility of restoring the Amiga hardware in the museum’s possession.” The effort necessitated acts of “forensic retrocomputing” — a delicate process, since “even reading the data from the diskettes entailed significant risk to the contents.” The CMU Computer Club team even had to reverse-engineer the “completely unknown file format” in which Warhol had saved his images. “By looking at these images, we can see how quickly Warhol seemed to intuit the essence of what it meant to express oneself, in what then was a brand-new medium: the digital,” Arcangel says in the press release. “FYI, it was the most fun project I ever worked on,” he says on his blog — a meaningful statement indeed, since so much of his other work involves old Nintendo games. The Hillman Photography Initiative captured it all in a film called Trapped: Andy Warhol’s Amiga Experiments, which premieres Saturday, May 10, at Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Library Lecture Hall, thereafter becoming viewable at nowseethis.org.

Related Content:

Andy Warhol Digitally Paints Debbie Harry with the Amiga 1000 Computer (1985)

Warhol’s Screen Tests: Lou Reed, Dennis Hopper, Nico, and More

Three “Anti-Films” by Andy Warhol: Sleep, Eat & Kiss

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.