In 1901, Vittorio Alinari, head of Fratelli Alinari, the world’s oldest photographic firm, decided to publish a new illustrated edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy. To do so, Alinari announced a competition for Italian artists: each competitor had to send illustrations of at least two cantos of the epic poem, which would result in one winner and a public exhibition of the drawings. Among the competitors were Alberto Zardo, Armando Spadini, Ernesto Bellandi, and Alberto Martini.

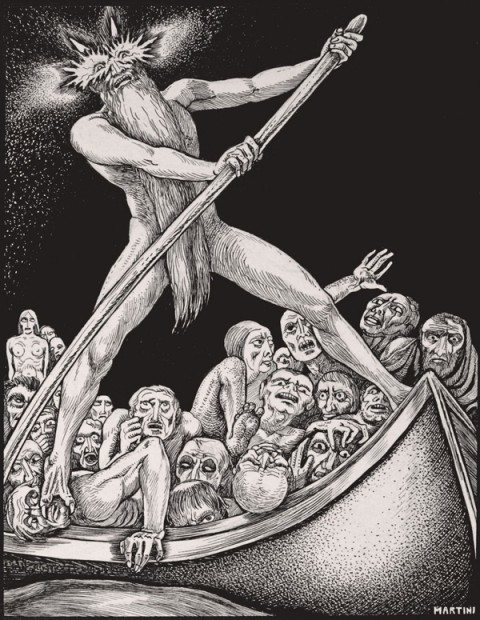

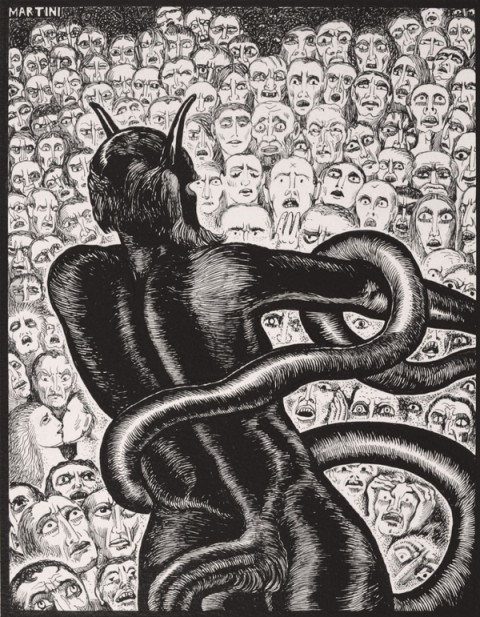

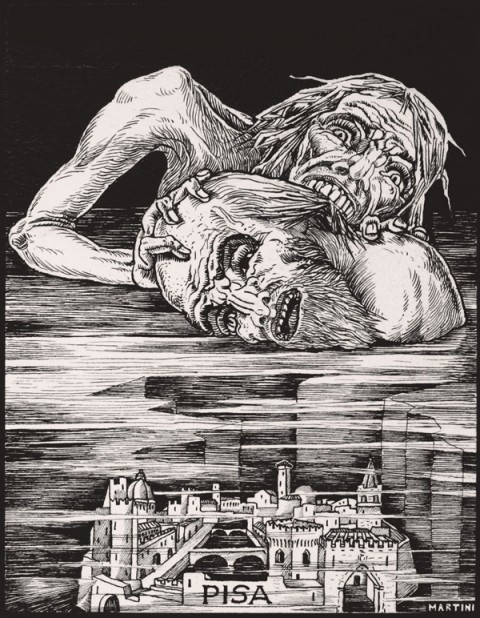

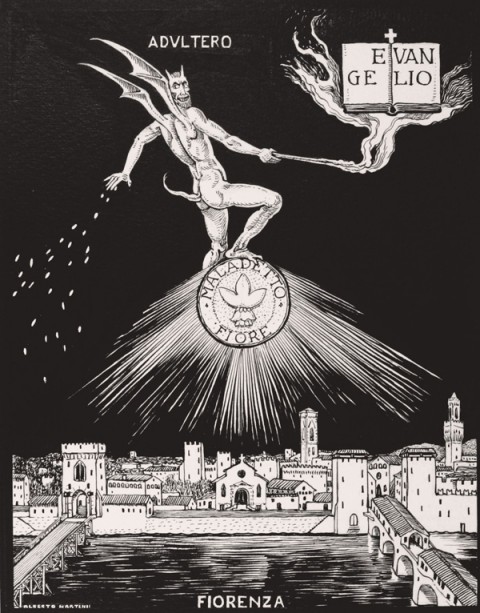

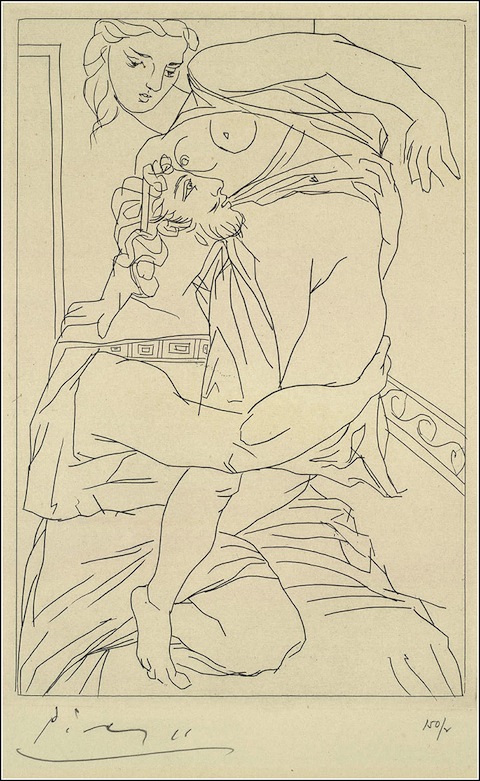

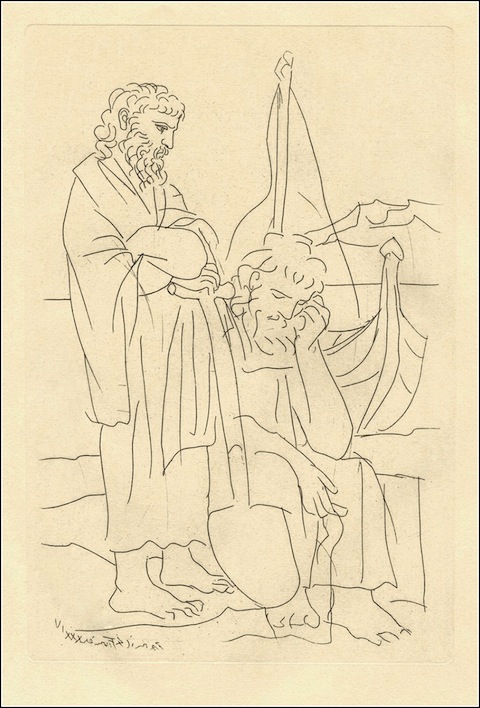

While Martini did not win the competition, he, as Vittorio Sgarbi wrote in his foreword to Martini’s La Divina Commedia, “seemed born to illustrate the Divine Comedy.” The 1901 contest was followed by two more sets of illustrations between 1922 and 1944, which produced altogether almost 300 works in a wide range of styles, including pencil and ink to the watercolor tables painted between 1943 and 1944. While repeatedly rejected publication during his lifetime, a comprehensive edition of Martini’s La Divinia Commedia is available today.

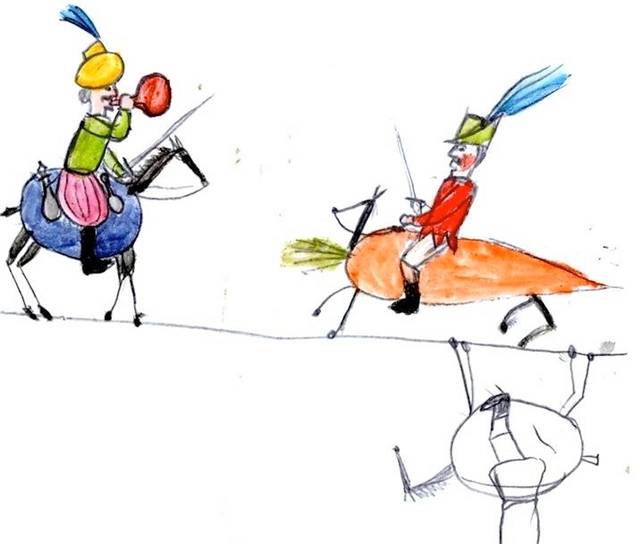

With his feeling for the grotesque and the macabre, Martini’s work was much more influenced by the Northern Mannerism movement than Italian art and is often seen as a precursor to Surrealism, as Martini was a favorite of André Breton. However, while steeped in the surrealism of Odilon Redon and Aubrey Beardsley black and white counterpoints, Martini’s Divine Comedy is filled with an original sense of fantasy and beautifully conveys Dante’s more abstract imagery. Needless to say, Martini’s interpretation was very much in a world apart from the Italian Futurist and Metaphysical movements of the day.

Ignored by Italian critics most his life, Martini continued to produce a large number of illustrations and painting until his death in 1954. As he wrote in his autobiography, “Only the true great artists do not age, because they are able to innovate and invent new forms, new colors, genuine inventions.” Martini’s Divine Comedy is as shocking and beautiful today as it was in the early twentieth century, and is the best example of Martini’s progression as an artist throughout his career.

For a very different artistic interpretation of the Divine Comedy, see our posts on editions by Salvador Dalí and Gustave Doré.

Related Content:

Physics from Hell: How Dante’s Inferno Inspired Galileo’s Physics

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

Salvador Dalí’s 100 Illustrations of Dante’s The Divine Comedy