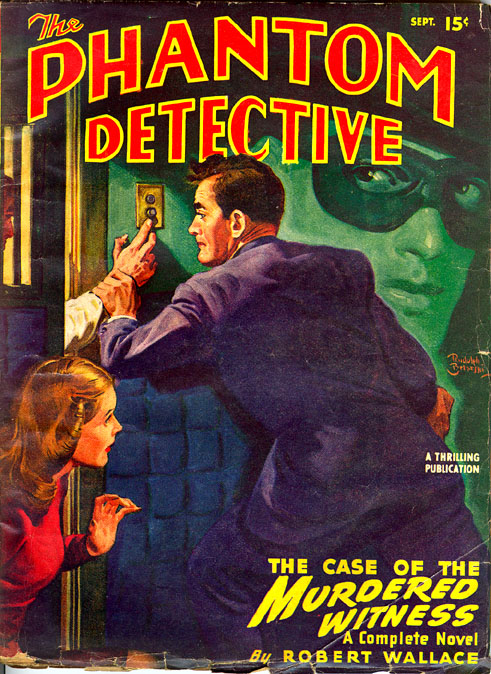

For the first half of the twentieth century, pulp magazines were a quintessential form of American entertainment. Printed on cheap, wood pulp paper, the “pulps” (as opposed to the “glossies” or “slicks,” such as The New Yorker) had names like The Black Mask and Amazing Stories, and promised readers supposedly true accounts of adventure, exploitation, heroism, and ingenuity. Such outlets offered a steady stream of work for stables of fiction writers, with content ranging from short stories about intrepid explorers saving damsels from Nazis/Communists (depending on the precise time of publication) to novel-length man vs. beast accounts of courage and cunning. This, incidentally, gave birth to the term “pulp fiction,” popularized in the 1990s by Quentin Tarantino’s eponymous film.

In the 1950s, the pulps went into a steep decline. In addition to television, paperback novels, and comic books, the pulps were overtaken by the more explicit, and even lower brow men’s adventure magazines (readers of Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood may remember Perry Smith, the sociopathic misfit who murdered the Clutter family, being an enthusiastic reader of these early lads’ mags). Thanks to The Pulp Magazines Project, however, many of the most famous publications remain accessible today through a well-designed online interface. Hundreds of issues have been archived in the database that spans from 1896 through to 1946. It includes large magazines, such as The Argosy and Adventure, and smaller, more specialized fare, such as Air Wonder Stories and Basketball Stories. Although good writing occasionally made its way into the pulps, don’t expect these magazines to mirror the literary depth of serialized publications of the 19th century; rather, the archive provides a terrifically entertaining look at the popular reading of early 20th century America.

To browse the complete database, head over to The Pulp Magazines Project.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Quentin Tarantino Gives Sneak Peek of Pulp Fiction to Jon Stewart (1994)

Isaac Asimov Recalls the Golden Age of Science Fiction (1937–1950)

Did Shakespeare Write Pulp Fiction? (No, But If He Did, It’d Sound Like This)

Download 14 Great Sci-Fi Stories by Philip K. Dick as Free Audio Books and Free eBooks