Note: It looks like the 92nd St Y took the reading off of its Youtube channel for unknown reasons. However you can stream it here.

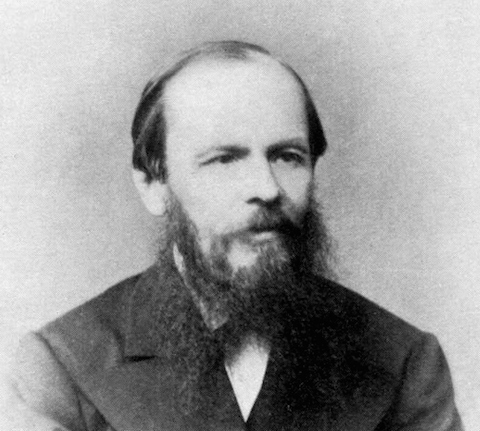

Haruki Murakami doesn’t make many public appearances, but when he does, his fans savor them. This recording of a reading he gave at New York’s 92nd Street Y back in 1998 (stream it here) counts as a treasured piece of material among English-speaking Murakamists, especially those who love his eighth novel, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. When asked to read from that book, the author explains here, he usually reads from chapter one, “but I’m tired of reading the same thing over and over, so I’m going to read chapter three today.” And that’s what he does after giving some background on the book, its 29-year-old protagonist Toru Okada, and his own thoughts on how it feels to be 29.

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, published in three parts in Japan in 1994 and 1995 and in its entirety in English in 1997, began a new chapter in the writer’s career. You could tell by its size alone: the page count rose to 600 in the English-language edition, whereas none of his previous novels had clocked in above 400. Thematically, too, Murakami’s mission had clearly broadened: where its predecessors concern themselves primarily with Western pop culture, disappearing girls, twentysomething languor, and mysterious animal-men, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle takes on Japanese history, especially the country’s ill-advised wartime colonial venture in Manchuria.

As a result, the book finally earned Murakami some respect — albeit respect he’d never directly sought — from his homeland’s long-disdainful literary establishment. Despite having held its place since the time of this reading as Murakami’s “important” book, and one many readers name as their favorite, it might not offer the easiest point of entry into his work. When I asked Wang Chung lead singer Jack Hues about a Murakami reference in the band’s song “City of Light,” he told me he put it there after reading The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle on his daughter’s recommendation and not liking it very much. I suggested he try Norwegian Wood instead.

Note: You can download a complete audio version of The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle if you take part in one of the free trials offered by our partners Audible.com and/or Audiobooks.com. Click on the respective links to get more information.

Related Content:

Haruki Murakami Lists the Three Essential Qualities For All Serious Novelists (And Runners)

Haruki Murakami’s Passion for Jazz: Discover the Novelist’s Jazz Playlist, Jazz Essay & Jazz Bar

A Photographic Tour of Haruki Murakami’s Tokyo, Where Dream, Memory, and Reality Meet

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture as well as the video series The City in Cinema and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.