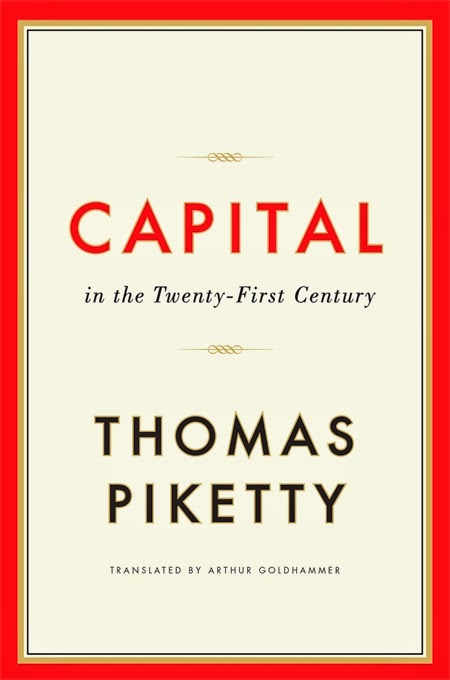

It’s hard to fathom, but somehow Thomas Piketty’s 696-page book Capital in the Twenty-First Century is No. 1 on the Amazon bestseller list. It’s a serious economics book that takes a long, hard look at the dynamics affecting the distribution of capital, the concentration of wealth, and the long-term evolution of inequality in advanced economies. Not exactly light reading. And yet it’s outselling Michael Lewis’ Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt (a lighter, more colorful study of the inequalities in the financial system); Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (the newly-named winner of the Pulitzer Prize in Fiction); and even The Little Golden Book version of Disney’s Frozen.

So what’s the book all about? One way to answer that question is to read the introduction to Capital, which you can find on the Harvard University Press website. There Piketty, a professor at the Paris School of Economics, gets right into the heart of the questions he’s trying to answer in Capital:

The distribution of wealth is one of today’s most widely discussed and controversial issues. But what do we really know about its evolution over the long term? Do the dynamics of private capital accumulation inevitably lead to the concentration of wealth in ever fewer hands, as Karl Marx believed in the nineteenth century? Or do the balancing forces of growth, competition, and technological progress lead in later stages of development to reduced inequality and greater harmony among the classes, as Simon Kuznets thought in the twentieth century? What do we really know about how wealth and income have evolved since the eighteenth century, and what lessons can we derive from that knowledge for the century now under way?

As for the answers, those are pretty well explained in a digest by the Harvard Business Review. Summarizing the book’s argument, HBR writes:

Capital (which by Piketty’s definition is pretty much the same thing as wealth) has tended over time to grow faster than the overall economy. Income from capital is invariably much less evenly distributed than labor income. Together these amount to a powerful force for increasing inequality. Piketty doesn’t take things as far as Marx, who saw capital’s growth eventually strangling the economy and bringing on its own collapse, and he’s witheringly disdainful of Marx’s data-collection techniques. But his real beef is with the mainstream economic teachings that more capital and lower taxes on capital bring faster growth and higher wages, and that economic dynamism will automatically keep inequality at bay. Over the two-plus centuries for which good records exist, the only major decline in capital’s economic share and in economic inequality was the result of World Wars I and II, which destroyed lots of capital and brought much higher taxes in the U.S. and Europe. This period of capital destruction was followed by a spectacular run of economic growth. Now, after decades of peace, slowing growth, and declining tax rates, capital and inequality are on the rise all over the developed world, and it’s not clear what if anything will alter that trajectory in the decades to come.

As for how this impacts life in the U.S., HBR summarizes Piketty’s argument as follows:

On this side of the Atlantic, wealth and income were less concentrated in the 19th century than in Europe. After a spike in top incomes that topped out in the late 1920s, the income distribution flattened out here again, albeit in less dramatic fashion than in Europe. Since the 1970s, though, the U.S. has seen a sharp and unparalleled increase in the percentage of income going to the top 1% and especially 0.1%. This has not been driven by the capital and inheritance dynamics at the heart of Piketty’s story. He attributes it instead to the rise of what he calls “supermanagers.” Piketty cites recent research that shows managers and financial professionals making up 60% of the top 0.1% of the income distribution in the U.S., and proposes that their skyrocketing pay is mainly the product of sharp declines in top marginal tax rates that made it worth managers’ while to bargain harder for raises. This isn’t the only explanation available, and Piketty’s discussion of U.S. inequality doesn’t carry the same historical authority as other parts of the book. But it surely is interesting that, as he and several co-authors report in a new article in the American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, the rise in the top-percentile income share in 13 countries was almost perfectly correlated with declines in top marginal tax rates in those countries. It’s also interesting that this huge rise in relative income inequality has brought no discernible economic benefit. Yes, the U.S. economy has grown a bit faster than those of other developed economies, but that’s purely because of population growth. Per-capita economic growth has been almost identical in the U.S. and Western Europe since 1980, and because of the skew towards the top here, U.S. median income has actually lost ground relative to other nations.

But why let HBR give you insight into Piketty’s thinking when Piketty can do it himself. Below we have a talk he gave at the Economic Policy Institute earlier this month. He starts speaking at the 5:30 mark.

And finally Paul Krugman’s review in the New York Review of Books — “We’re in a New Gilded Age” — is worth a read.

Related Content:

Free Economics Courses Online

Reading Marx’s Capital with David Harvey (Free Online Course)

The History of Economics & Economic Theory Explained with Comics, Starting with Adam Smith