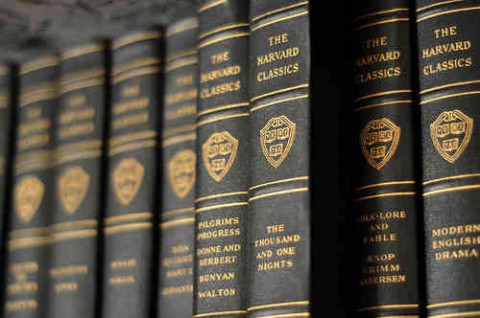

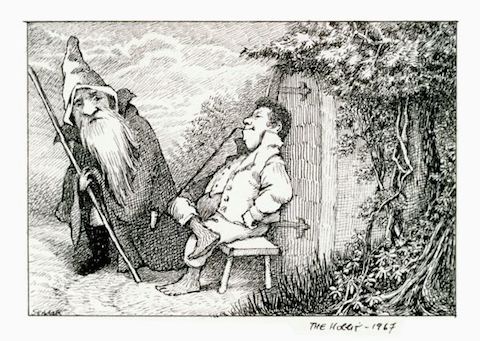

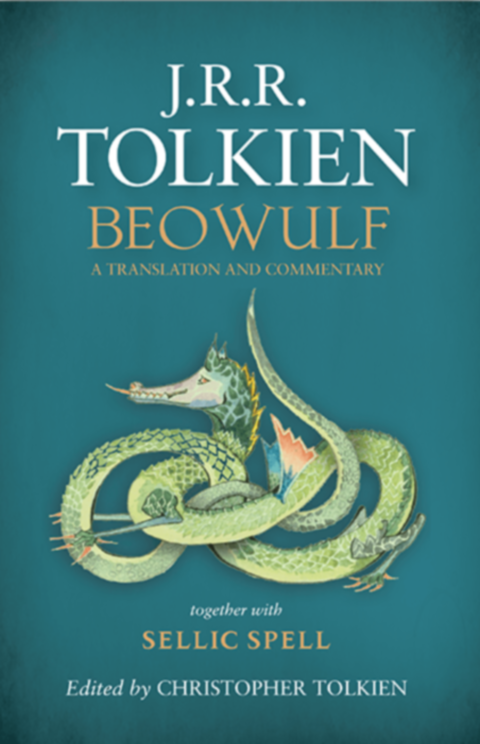

For the first time, J.R.R. Tolkien’s 1926 translation of the 11th century epic poem Beowulf will be published this May by HarperCollins, edited and with commentary by his son Christopher. The elder Tolkien, says his son, “seems never to have considered its publication.” He left it along with several other unpublished manuscripts at the time of his death in 1973. The edition will also include a story called Sellic Spell and excerpts from a series of lectures on Beowulf Tolkien delivered at Oxford in the 1930s. Tolkien did publish one of those lectures, “The Monster and the Critic,” in 1936. In this “epoch-making paper,” writes Seamus Heaney in the introduction to his hugely popular 1999 dual language verse edition, Tolkien treated the Beowulf poet as “an imaginative writer,” not a historical reconstruction. His “brilliant literary treatment changed the way the poem was valued and initiated a new era—and new terms—of appreciation.” This very same thing could be said of Heaney’s translation which, true to his stated goals, brought the poem out of academic conferences and classrooms and into living rooms and coffee shops everywhere. (You can hear Heaney read from that translation here.)

Nowhere in Heaney’s introduction to his version does he mention Tolkien’s translation of the poem, so we must presume he did not know of it. Long before Tolkien’s lectures and translation, Beowulf had been perhaps the most revered poem in the English language, at least since the 18th century, when the sole manuscript was rescued from fire and and translated and disseminated widely. Despite that status, Beowulf was not actually written in English—not an English we would recognize—but in Old English, or Anglo-Saxon. As readers of Heaney’s dual translation will know, that distant provincial ancestor of the modern global language, named for the mixture of Germanic peoples who inhabited England 1000 years ago, appears mostly alien to us now. (To add to the strangeness, its unfamiliar alphabet once consisted entirely of runes).

The poem, moreover, is not set in England, but where Shakespeare set his Hamlet, Denmark. Its titular hero, a prince from Geat (ancient Sweden), stalks a monster named Grendel on behalf of Danish king Hroðgar, killing the monster’s mother along the way. Tolkien’s almost universally beloved body of fiction was deeply influenced by Beowulf. Nevertheless, his translation may be less accessible than Heaney’s, though no less beautiful, perhaps, for different reasons. In Heaney’s verse, one hears Ted Hughes, some echoes of Milton, Heaney’s own voice. If we are to credit the redditor who posted a now-defunct 2003 article from Canadian newspaper National Post that quotes from Tolkien’s translation, the Hobbit author’s verse hews to a more direct correspondence with the Anglo Saxon, a language made of giant rocks and timber and crashing waves, not elegant, elaborated clauses. The National Post article announces the discovery at Oxford of the Tolkien translation by English Professor Michael Drout (a story he’s since debunked), and quotes from both Heaney and Tolkien. See the comparison below:

Heaney’s translation:

Time went by, the boat was

on water,

in close under the cliffs.

Men climbed eagerly up the

gangplank,

sand churned in surf, warriors

loaded

a cargo of weapons, shining

war-gear

in the vessel’s hold, then

heaved out,

away with a will in their

wood-wreathed ship.

Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf and his men setting sail:

On went the hours:

on

ocean afloat

under cliff was their craft.

Now climb blithely

brave man aboard;

breakers pounding

ground the shingle.

Gleaming harness

they hove to the bosom of the

bark, armour

with cunning forged then cast

her forth

to voyage triumphant,

valiant-timbered

fleet foam twisted.

One wonders what the recently departed Irish poet would have said had he lived to read this Tolkien edition. Might it, as Heaney said of his lectures, change the way the poem is valued? Or might he see it resembling other difficult attempts to make modern English replicate the strongly inflected built-in rhythms of Anglo-Saxon—a language, Tolkien once said, from “the dark heathen ages beyond the memory of song.”

You can pre-order a copy of Tolkien’s translation of Beowulf here.

Related Content:

Seamus Heaney Reads His Exquisite Translation of Beowulf and His Memorable 1995 Nobel Lecture

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

“The Tolkien Professor” Presents Three Free Courses on The Lord of the Rings

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness