Amazon’s Books editors set out to compile a list of 100 Books to Read in a Lifetime, with a few goals in mind:

Amazon’s Books editors set out to compile a list of 100 Books to Read in a Lifetime, with a few goals in mind:

We wanted the list to cover all stages of a life (which is why you’ll find children’s books in here), and we didn’t want the list to feel like homework. Of course, no such list can be comprehensive – our lives, we hope, are long and varied – but we talked and argued and sifted and argued some more and came up with a list, our list, of favorites. What do you think? How did we do?

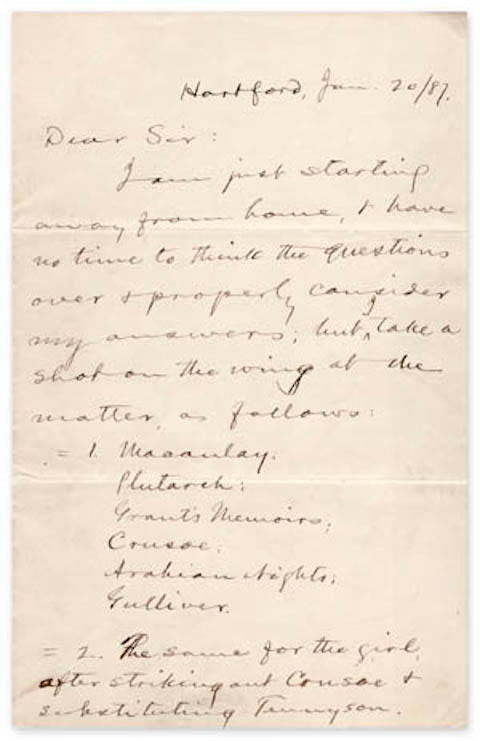

Overall pretty well. That’s how I’d answer the editors’ rhetorical question. The list doesn’t pander to the lowest common denominator of reading tastes. It features substantive works by Albert Camus, Alice Munro (see our collection of free Munro stories), Ralph Ellison, Robert A. Caro, Haruki Murakami, Rebecca Skloot and many others. It’s a hearty list, so far as these lists go, offering plenty of good selections for someone seeking a new read. But let me add this one caveat. If the Amazon editors didn’t sell out, they did intend to sell. Or so it seems to skeptical me. Of the 100 books on the list, only a handful are older works in the public domain and thus free. Maybe the Amazon editors would claim that reading books written a century ago is tantamount to homework. But that seems fairly short-sighted. All of this reminds me of a post we wrote last year called The 10 Greatest Books Ever, According to 125 Top Authors. Here we looked back at a 2007 book called The Top Ten: Writers Pick Their Favorite Books where editor J. Peder Zane asked 125 top writers to name their favorite books — writers like Norman Mailer, Annie Proulx, Stephen King, Jonathan Franzen, Claire Messud, and Michael Chabon. The lists were all compiled in an edited collection, and then prefaced by one uber list, “The Top Top Ten.” All but one book in the top 10 was written before 1931 (which means they’re almost entirely free and available in our Free eBooks and Free Audio Books collections). It just goes to show, I suppose, that one person’s homework is another person’s read of a lifetime. Feel free to sift through both lists (here & here) and see which texts belong on your personal bucket list.

Related Content:

The 10 Greatest Books Ever, According to 125 Top Authors (Download Them for Free)

Nabokov Reads Lolita, Names the Great Books of the 20th Century

18 (Free) Books Ernest Hemingway Wished He Could Read Again for the First Time

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

F. Scott Fitzgerald Creates a List of 22 Essential Books, 1936