Note: Elmore Leonard, the crime writer who gave us Get Shorty, Freaky Deaky, and Glitz, died at his home in Bloomfield Village, Michigan. He was 87. If you never had a chance to read Leonard, you can start with “Ice Man,” a 2012 story that appeared in The Atlantic. It’s free online. You can also get a feel for his writing by revisiting a post written here by Mike Springer last year. It gives an overview of Leonard’s tips for aspiring writers. And, in so doing, it provides valuable insight into how Leonard approached his craft. Elmore Leonard’s Ultimate Guide for Would-Be Writers is reprinted in full below.

“If it sounds like writing,” says Elmore Leonard, “I rewrite it.”

Leonard’s writing sounds the way people talk. It rings true. In novels like Get Shorty, Rum Punch and Out of Sight, Leonard has established himself as a master stylist, and while his characters may be lowlifes, his books are received and admired in the highest circles. In 1998 Martin Amis recalled visiting Saul Bellow and seeing Leonard’s books on the old man’s shelves. “Bellow and I agreed,” said Amis, “that for an absolutely reliable and unstinting infusion of narrative pleasure in a prose miraculously purged of all false qualities, there was no one quite like Elmore Leonard.”

In 2006 Leonard appeared on BBC Two’s The Culture Show to talk about the craft of writing and give some advice to aspiring authors. In the program, shown above, Leonard talks about his deep appreciation of Ernest Hemingway’s work in general, and about his particular debt to the 1970 crime novel The Friends of Eddie Coyle, by George V. Higgins. While explaining his approach, Leonard jots down three tips:

- “You have to listen to your characters.”

- “Don’t worry about what your mother thinks of your language.”

- “Try to get a rhythm.”

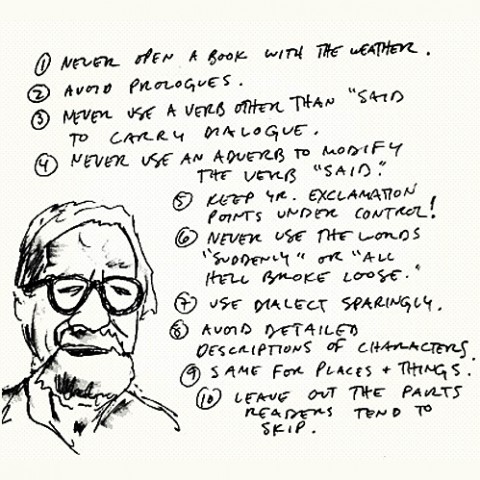

“I always refer to style as sound,” says Leonard. “The sound of the writing.” Some of Leonard’s suggestions appeared in a 2001 New York Times article that became the basis of his 2007 book, Elmore Leonard’s 10 Rules of Writing. Here are those rules in outline form:

You can read more from Leonard on his rules in the 2001 Times article. And you can read his new short story, “Ice Man,” in The Atlantic.