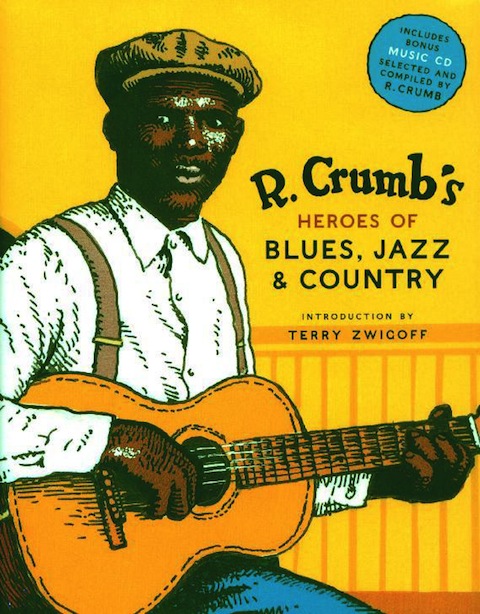

It was one of my favorite gifts of Christmas 2006. No, all apologies to everyone who bought me thoughtful gewgaws, but it was, without a doubt, the favorite. A humble, unassuming package contained a veritable encyclopedia of Americana: over one hundred portraits of jazz, blues, and country artists from the golden eras of American music, all drawn by a foremost antiquarian of pre-WWII music, R. Crumb. Beside each portrait—some made with Crumb’s exaggerated proportions and thick-lined shading, some softer and more realist—was a brief, one-paragraph bio, just enough to situate the singer, player, or band within the pantheon.

Though a fan of this sort of thing may think that it could get no better, glued to the back cover was a slipcase containing a CD with 21 tracks—seven from each genre. A quick scan showed a few familiar names: Skip James, Charlie Patton, Jelly Roll Morton. Then there were such unknown entities as Memphis Jug Band, Crockett’s Kentucky Mountaineers, and East Texas Serenaders, culled from Crumb’s enormous, library-size archive of rare 78s. Joy to the world.

Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz & Country began in the 80s with a series of illustrated trading cards, as you can see in the video above (which only covers the blues and jazz corners of the triangle). The first cards, “Heroes of the Blues,” came attached to old-time reissues from the Yazoo record company. Eventually expanding the cards to include jazz and country, working in each category from old photos or newsreel footage, Crumb covered quite a lot of musico-historical ground. Archivists and authors Stephen Calt, David Jasen, and Richard Nevins wrote the short blurbs. Finally Yazoo, rather than issuing the cards individually with each record, combined them into boxed sets.

The book—which validates my sense that this music belongs together cheek by jowl, even if some of its partisans can’t stand each other’s company—evolved through a painstaking process in which Crumb redrew and recolored the original illustrations from the printed trading cards (the original artwork having disappeared). You can follow one step of that process in a detailed description of Crumb’s conversion of the blues cards to a silkscreened poster. Crumb’s process is as thorough as his period knowledge. But Crumb fans know that the comic artist’s reverence for Americana goes beyond his collecting and extends to his own version of kitchen-sink bluegrass, blues, and jazz. Listen to Crumb on the banjo above with his Cheap Suit Serenaders. And if anyone feels like getting me a Christmas present this year, I’d like a copy of their record Chasin Rainbows. On vinyl of course.

Related Content:

A Short History of America, According to the Irreverent Comic Satirist Robert Crumb

Record Cover Art by Underground Cartoonist Robert Crumb

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness