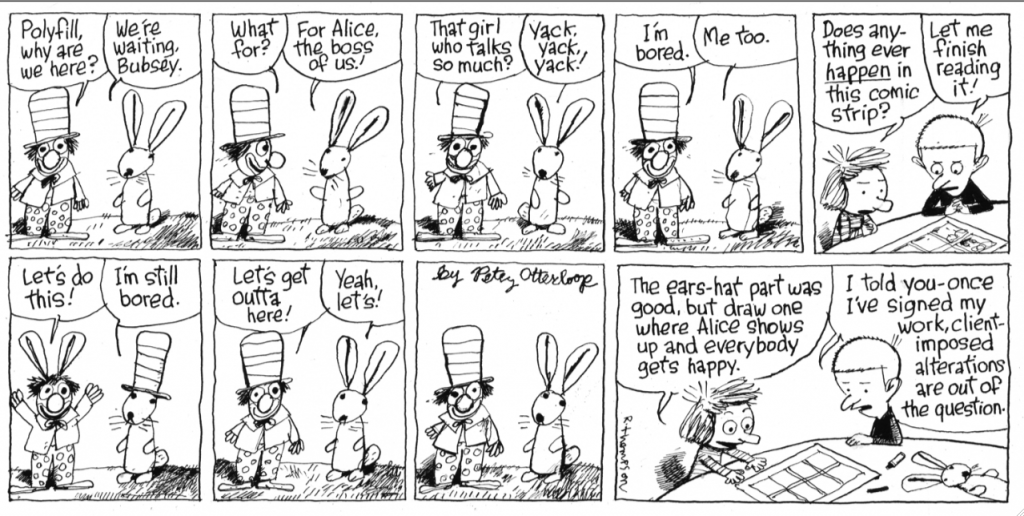

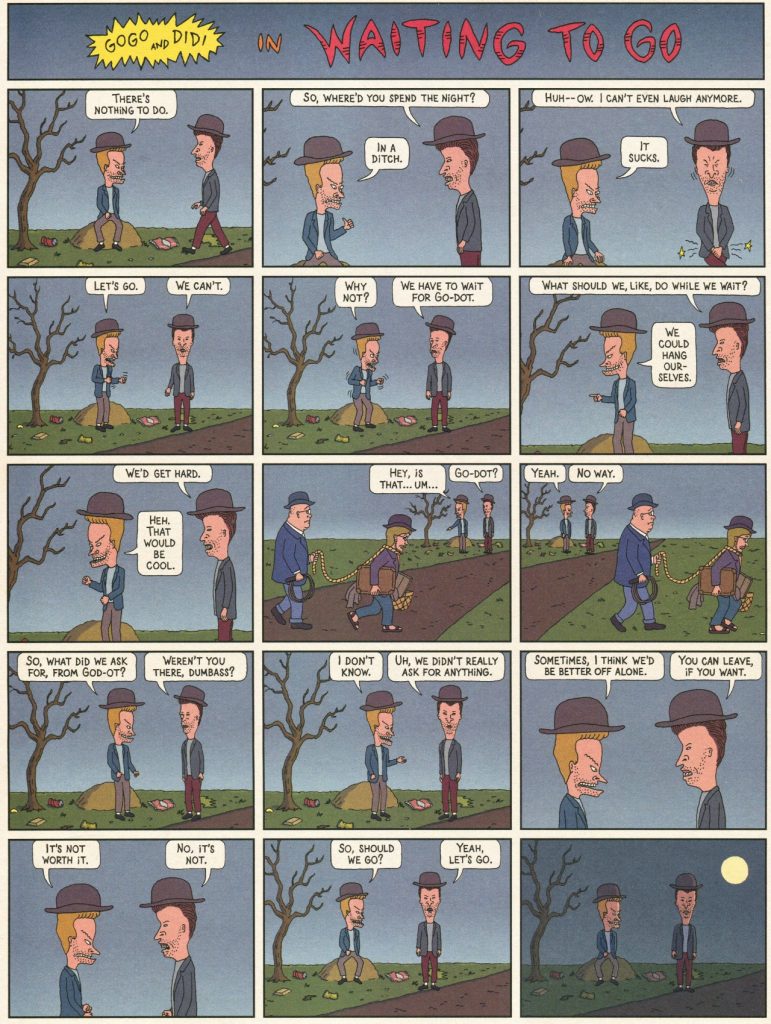

It is surprising to me, but a few people I’ve come across don’t know the name of cartoonist Robert Crumb, cult hero of underground comics and obscure Americana record collecting. On second thought, maybe this shouldn’t come as such a surprise. These are some pretty small worlds, after all, populated by obsessive fans and archivists and not always particularly welcoming to outsiders. But Crumb is different. For all his social awkwardness and hyper-obsessiveness, he seems strangely accessible to me. The easiest reference for those who’ve never heard of him is Steve Buscemi’s Seymour in Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World. There’s an obvious tribute to Crumb in the character (Zwigoff previously made an R. Crumb documentary), though it’s certainly not a one-to-one relation (the film adapts Daniel Clowe’s comic of the same name.)

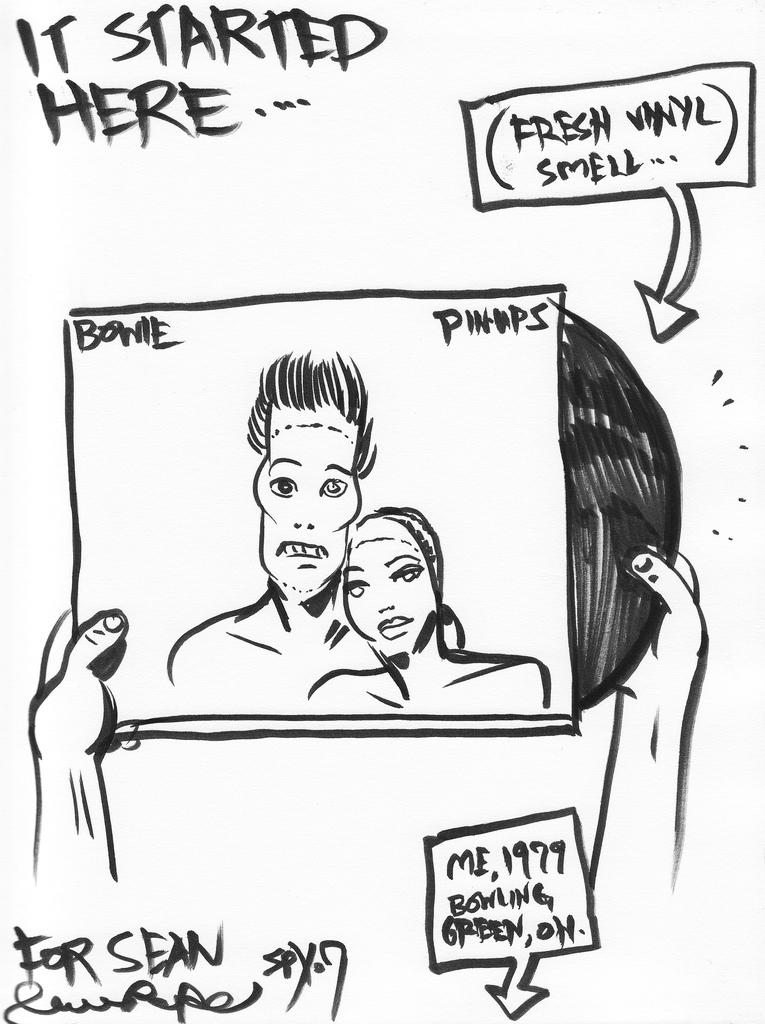

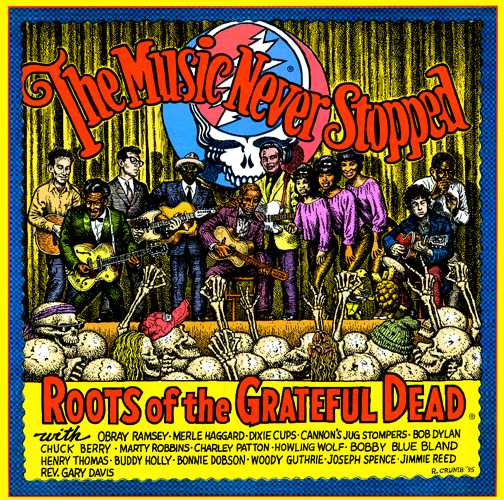

Whether or not Ghost World (or Zwigoff’s Crumb) rings a bell, there’s still the matter of how to communicate the lovable lewdness and aggressive anachronism that is Crumb’s art. For that one may only need to mention Big Brother & the Holding Company’s 1968 classic Cheap Thrills (top), the first album cover Crumb designed—and which Janis Joplin insisted upon over the record company’s objections. With its focus on musicians, and its appropriation of hippie weirdness, racist American imagery, and an obsession with female posteriors that rivals Sir-Mix-a-Lot’s, the cover pretty much spans the spectrum of perennial Crumb styles and themes. Above, see another of Crumb’s covers, for a compilation called The Music Never Stopped: Roots of the Grateful Dead, which collects such roots and old-school rock and roll artists as Merle Haggard, Chuck Berry, Bob Dylan, Reverend Gary Davis, Howlin’ Wolf, and more.

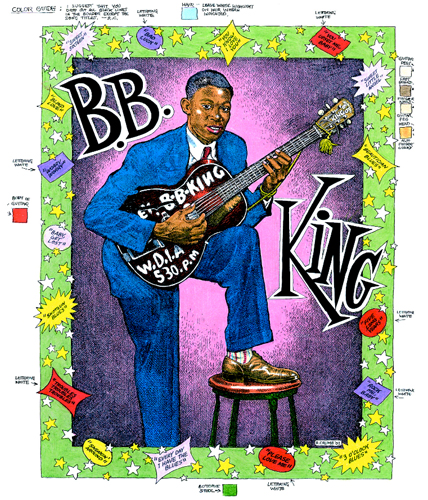

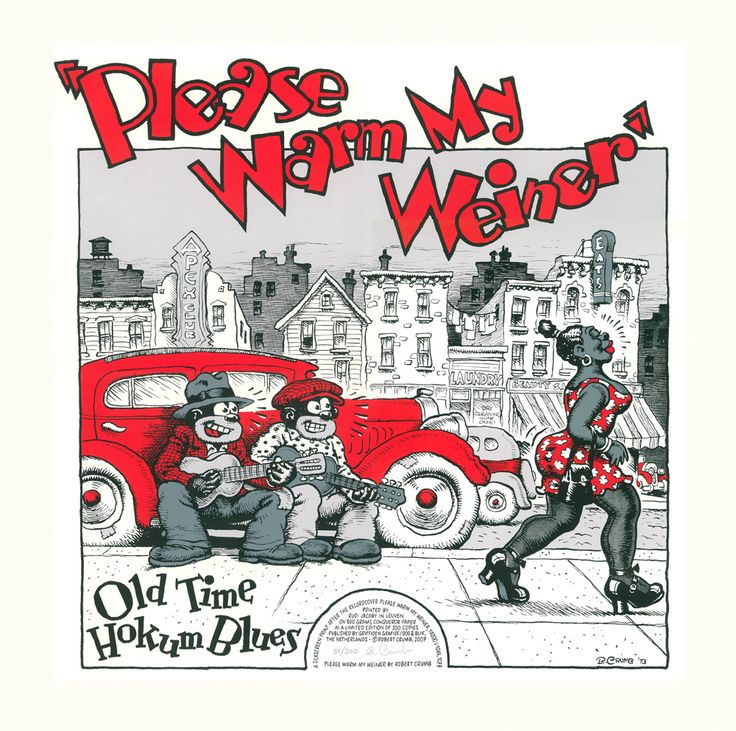

Though he objected to the 1995 assignment—saying to Shanachie Records, “You want all these people on a CD cover? What are they, like, five inches across?”—Crumb must have relished the subject. (And he was paid, as per usual, in vintage 78s.) Next to those posteriors, Crumb’s true love has always been American roots music—ragtime, swing, old country and bluegrass, Delta country blues—and he has spent a good part of his career illustrating artists he loves, and those he doesn’t. From famous names like Joplin, Dylan, and B.B. King (above, whose music Crumb said he “didn’t care for, but I don’t find it that objectionable either”), to much more obscure artists, like Bo Carter, known for his “Please Warm My Wiener,” on the 1974 compilation album below.

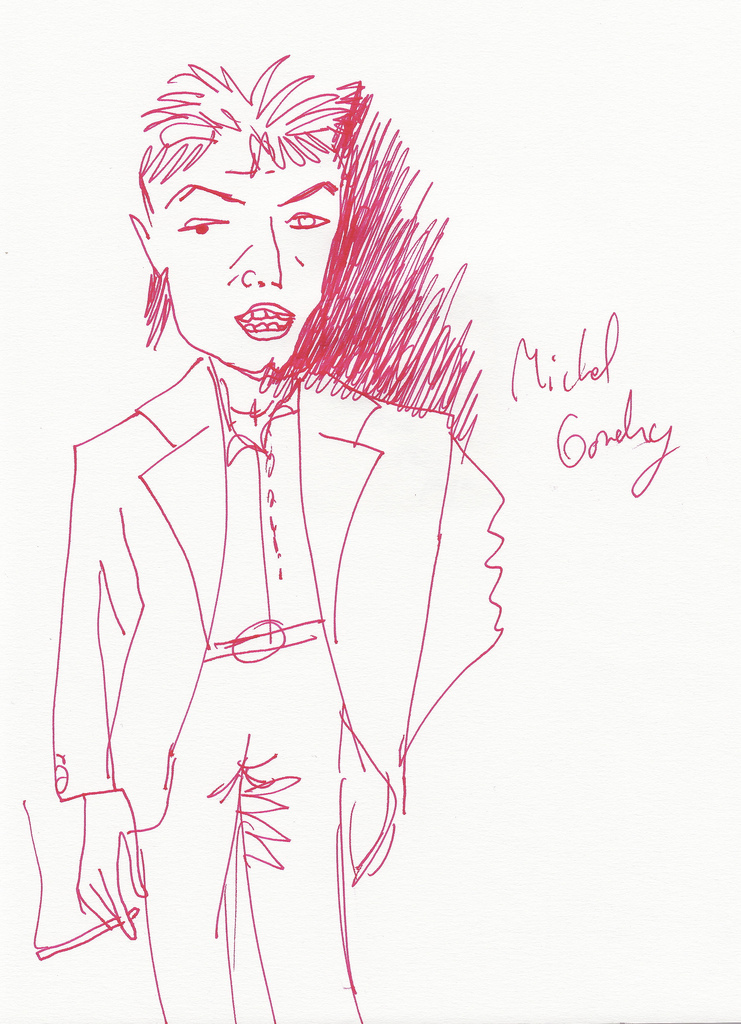

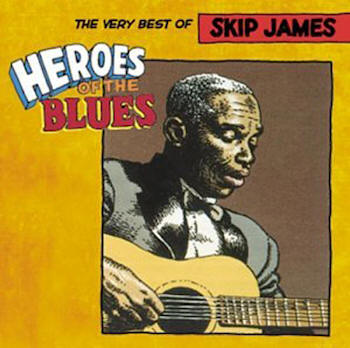

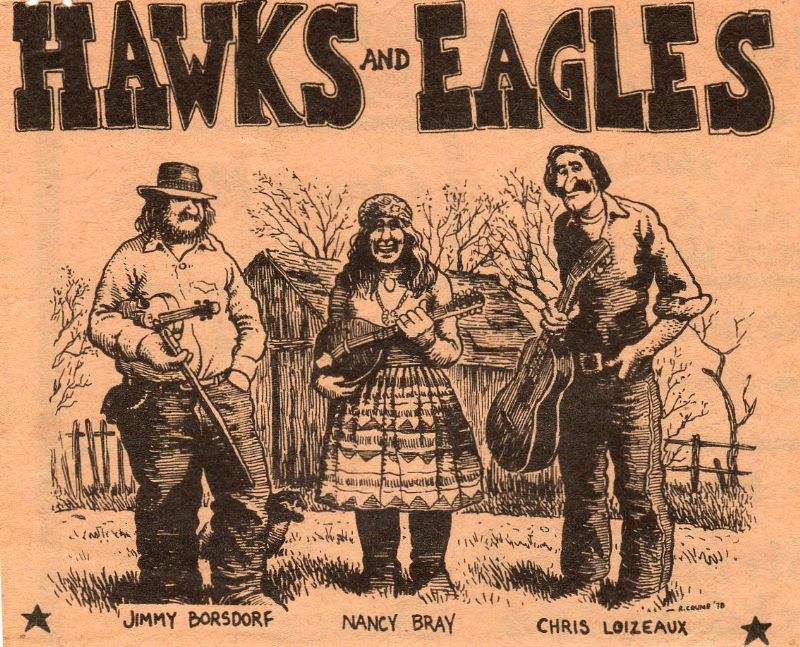

Crumb’s use of racially questionable and sexist imagery—however satirical—has perhaps rendered him untouchable in some circles, and it’s hard to imagine many of his album covers passing corporate muster these days. His recent work has moved toward more straightforward, respectful portraiture, like that of King and of Skip James on the best-of below, from a series called “Heroes of the Blues.” (Crumb also illustrated “Heroes of Jazz” and “Heroes of Country,” as we featured in this post.) See Crumb’s inimitable, looser portrait style again further down in 2002 album art for a group called Hawks and Eagles.

Crumb may have shed some of his more unpalatable tendencies, but he hasn’t lost his lascivious edge. However, his work has matured over the years, taking on serious subjects like the book of Genesis and the Charlie Hebdo massacre. For an artist with such peculiar personal focus, Crumb is surprisingly versatile, but it’s his album covers that combine his two greatest loves. “What makes Crumb’s art so appropriate for the album sleeve,” writes The Guardian’s Laura Barton, “is its vividness, and its certain oomph; it’s in the mingling of sex and joy and compulsion, and the vibrancy and movement of his illustrations.”

Crumb hasn’t only combined his art with music fandom, but also with his own musicianship, illustrating covers for several of his own albums by his ragtime band Cheap Suit Serenaders. And he even provided the illustration for the soundtrack to his own documentary, as you can see above—an extreme example of the many self-abasing portraits Crumb has drawn of himself over the years. Crumb’s album cover art has been collected in a book, and you can see many more of his covers at Rolling Stone and on this list here.

Related Content:

A Short History of America, According to the Irreverent Comic Satirist Robert Crumb

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness