Since Charles Burns’ ‘70s-set sex-horror graphic novel Black Hole won a Harvey, Eisner, and an Ignatz Award in 2006, Hollywood has been toying with bringing the cartoonist’s dark visions to the screen. David Fincher was rumored to be developing Black Hole, until he picked up a copy of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo instead.

But why wait to see Burns turned into a live-action film when the comic artist himself wrote and directed a segment for an animated French horror anthology called Peur(s) du noir/Fear(s) of the Dark in 2007.

The film never received American distribution, which is a shame, because this CG-animation brings Burns’ beautiful black and white brushwork to life, with a story of a college romance gone horribly, obsessively wrong. It’s close in subject matter to the “bug” at the center of Black Hole, but (maybe it’s the French dialog) with a nouvelle vague twist. There are creepy insects aplenty, too.

The film also contains animated horror tales directed by other cartoonists who might not be as familiar to American audiences: Blutch, Marie Caillou, Pierre di Sciullo, Lorenzo Mattotti, and Richard McGuire. Having seen the whole film, despite being hit-and-miss like all anthology features, it makes one wish there was more opportunities for comic artists to venture into film without having to compromise for live action, or exhaust an idea for a big budget.

In the meantime, the future of a live action Black Hole is up in the air. According a year-old posting on ScreenRant, Fincher was out and Rupert Sanders was in. But that was before he signed on to direct a live action version of the manga Ghost in the Shell (with ScarJo!). However, he did have the idea to make an 11-minute short film teaser just in case.

Related Content

The Confessions of Robert Crumb: A Portrait Scripted by the Underground Comics Legend Himself (1987)

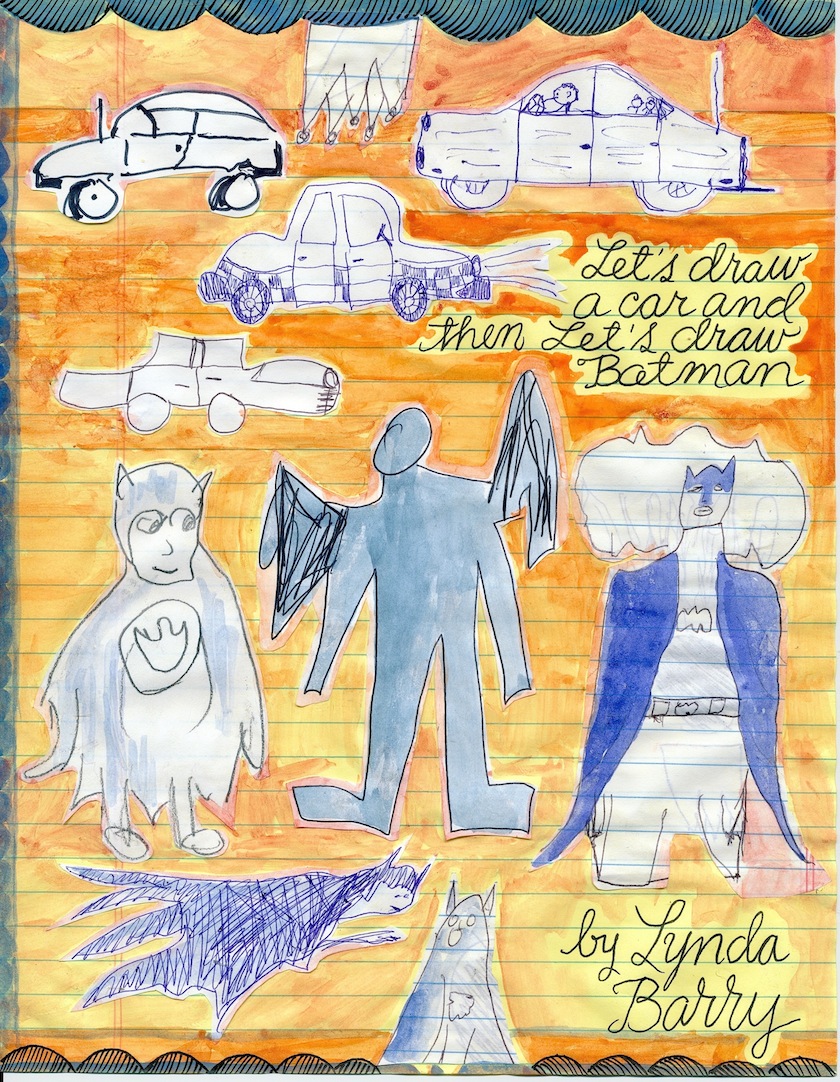

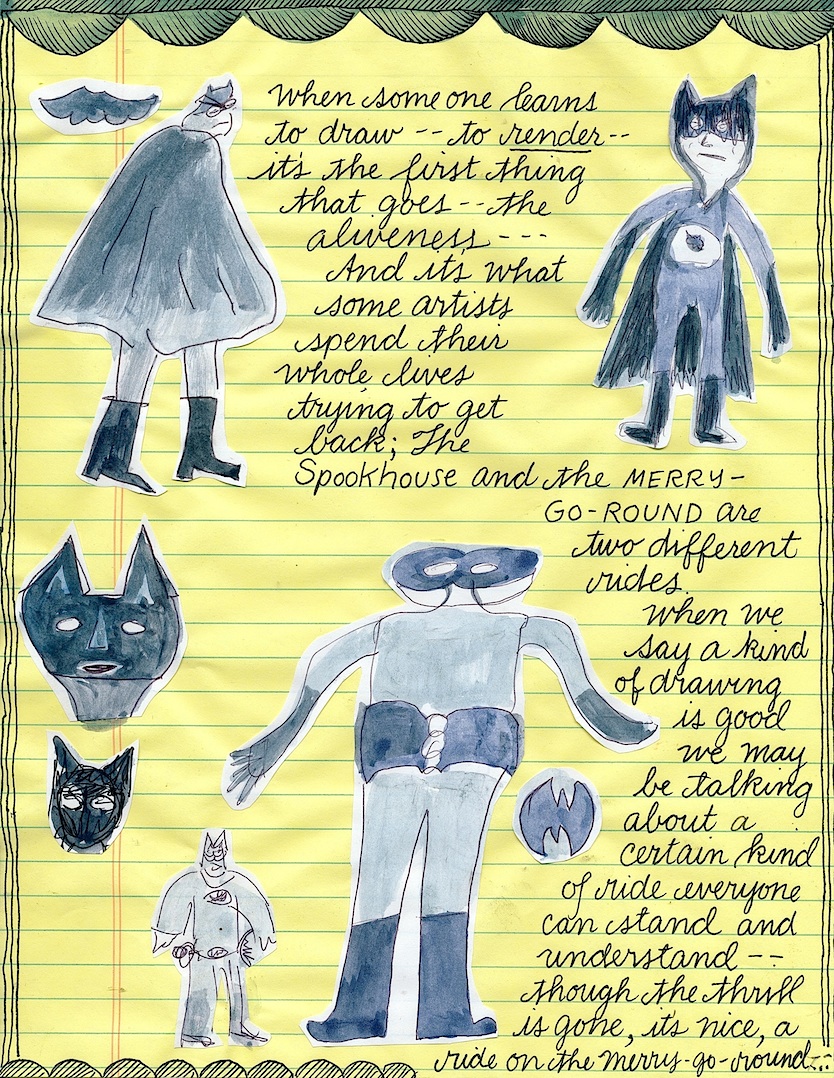

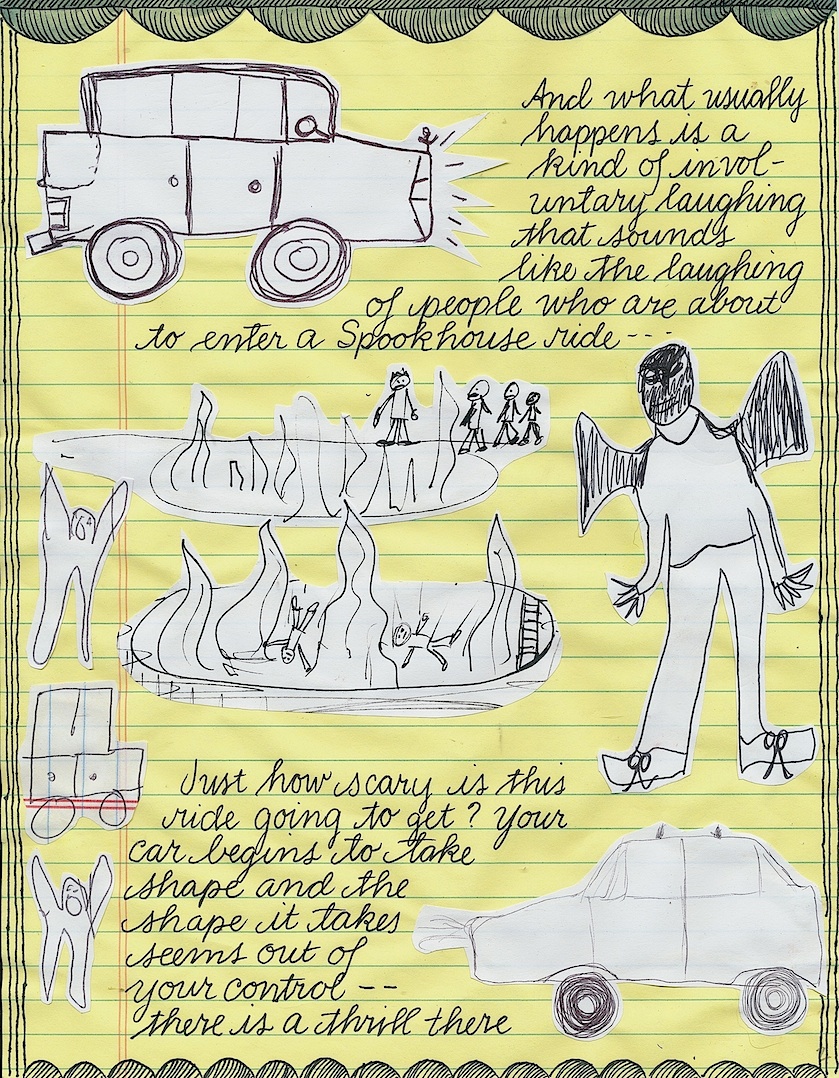

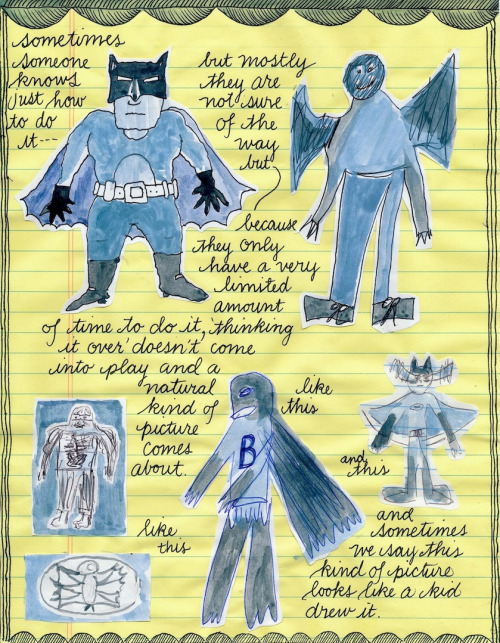

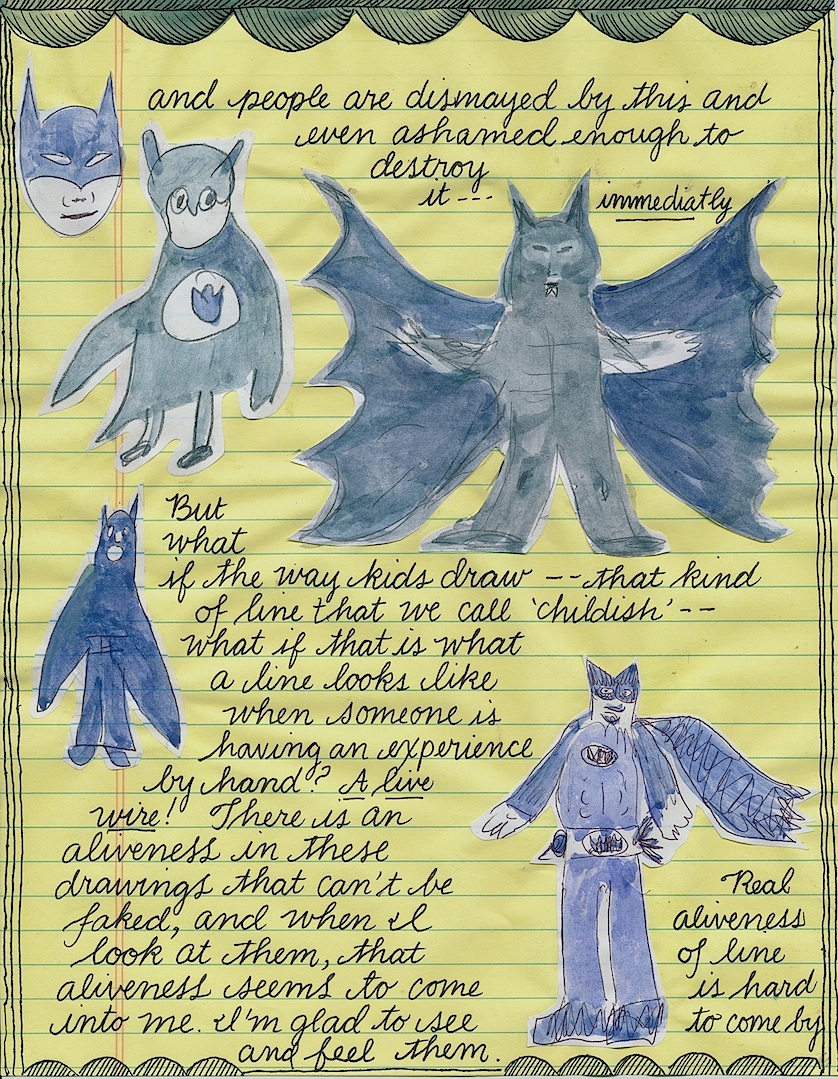

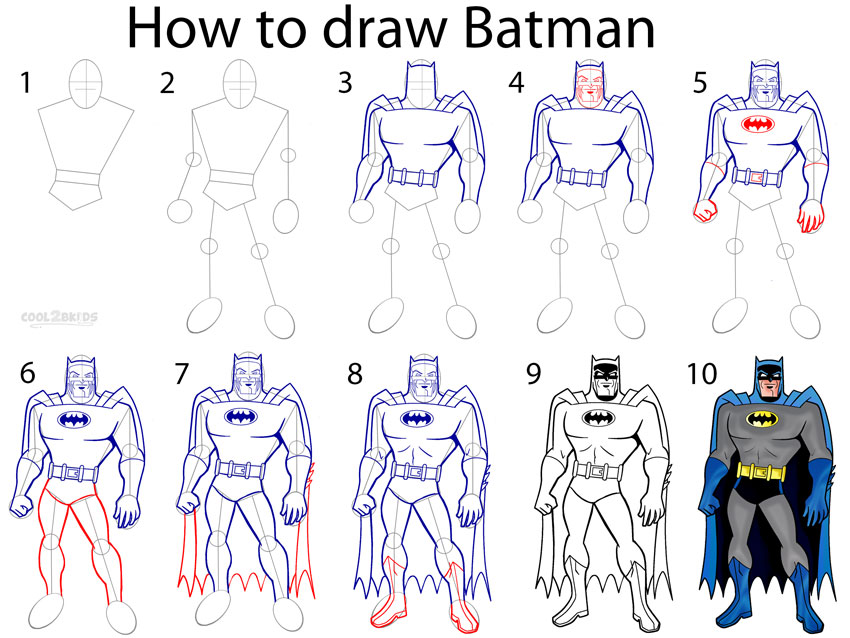

Cartoonist Lynda Barry Shows You How to Draw Batman in Her UW-Madison Course, “Making Comics”

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills and/or watch his films here.