“Like most people who make it in the art world, I bought a yacht to cruise the Med,” Banksy wrote on Instagram when introducing the Louise Michel, a vessel tasked with a somewhat different mission than an arriviste party boat: picking up refugees from countries like Libya and Turkey lost at sea. Anyone who’s followed Banksy’s art career knows he possesses a well-developed instinct for catching and keeping public attention, and it has hardly deserted him in this venture. Why sponsor a refugee rescue boat, after all, when you can sponsor a bright pink feminist refugee rescue boat, emblazoned with a piece of original art?

Despite having been named for the 19th-century feminist anarchist Louise Michel, the motor yacht’s operations encompass an even wider variety of causes: The Guardian’s Lorenzo Tondo and Maurice Stierl quote “Lea Reisner, a nurse and head of mission for the first rescue operation,” saying that the project is also “meant to bring together a variety of struggles for social justice, including for women’s and LGBTIQ rights, racial equality, migrants’ rights, environmentalism and animal rights.” This multidirectional activism would seem to suit the artistic sensibility of Banksy, whose work strikes out in as many critical directions as both his admirers and detractors can interpret.

The Louise Michel, as Tondo and Stierl reported last Thursday, “set off in secrecy on 18 August from the Spanish seaport of Burriana, near Valencia, and is now in the central Mediterranean where on Thursday it rescued 89 people in distress, including 14 women and four children.” After picking up the first group of refugees, reports the Washington Post’s Miriam Berger, “it then encountered a ship traveling from North Africa to Europe with 130 people aboard and some bodies of people who had died during the journey,” and as a result “quickly became overcrowded and could not properly steer, its Twitter posts said.” All this happened “at sea around 55 miles southeast of Lampedusa, an Italian island off the North African coast that has become a migration transit point.”

Hours later two other vessels, one operated by the Italian coast guard and one by a German nongovernmental organization, came to take on passengers. Though hardly smooth sailing, the Louise Michel’s first rescue mission proceeded more favorably than some: “A vessel named the Talia, which rescued 52 people almost two months ago, wasn’t allowed into the port for 5 days,” says Dazed. “Now, a boat named the Etienne is in the longest record stand-off between authorities and rescuers ever, having spent three weeks at sea being denied disembarkation in Malta.” Banksy publicized the Louise Michel, which he sponsors without involvement in its operations, only after it had set sail. But for anyone with an interest in showing the world the dire circumstances of refugees today, the highly visible boat’s highly visible difficulties certainly aren’t bad publicity.

Related Content:

Banksy Strikes Again in Venice

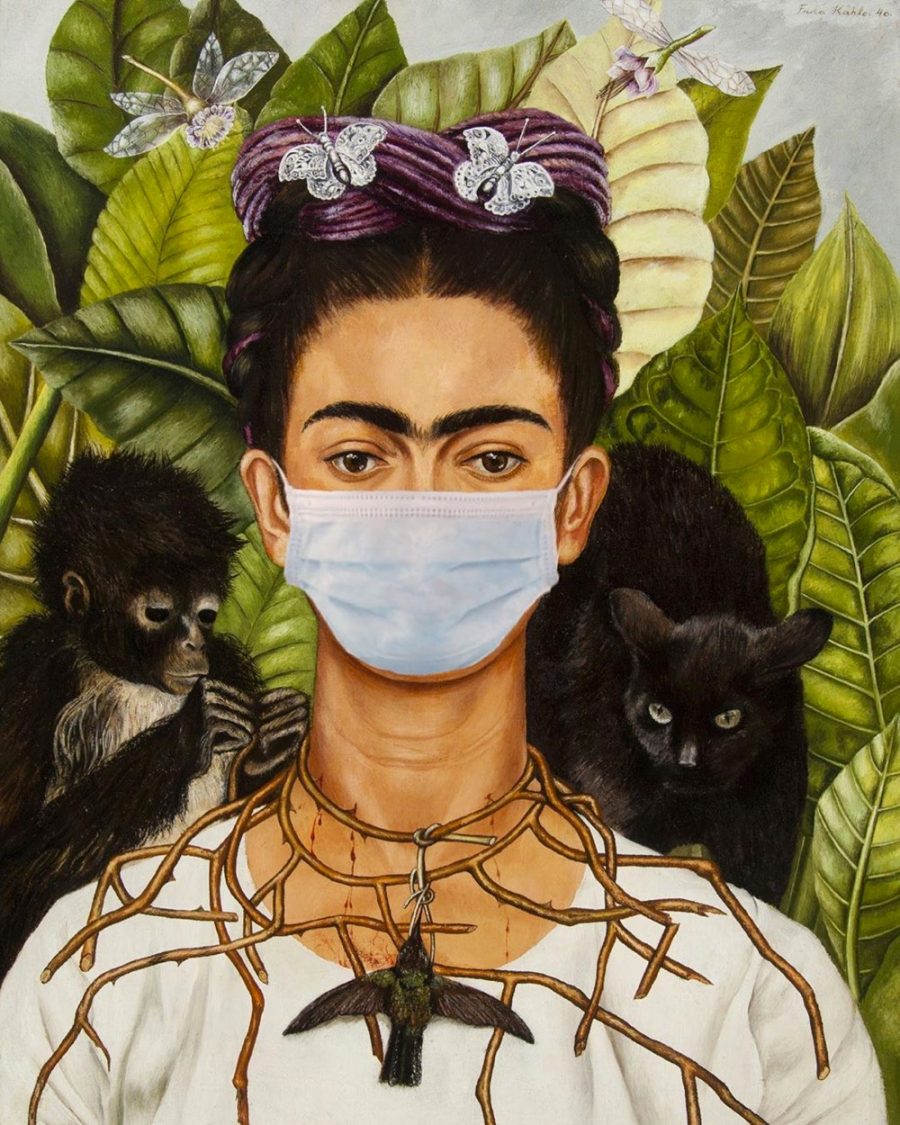

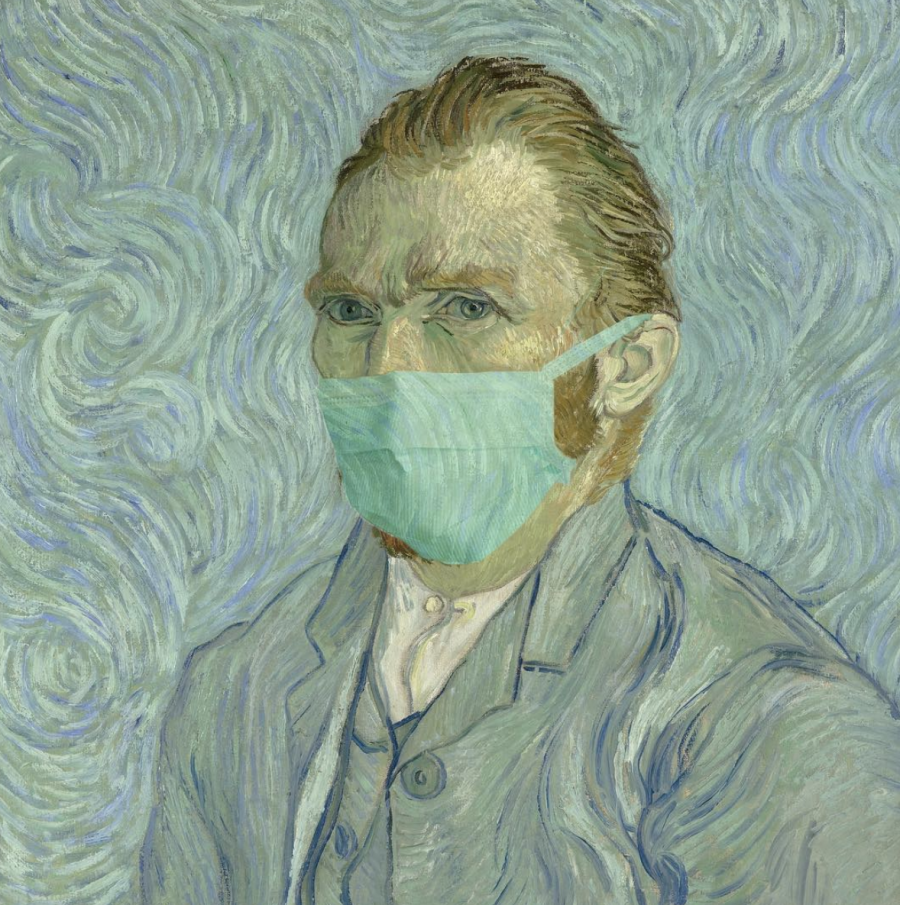

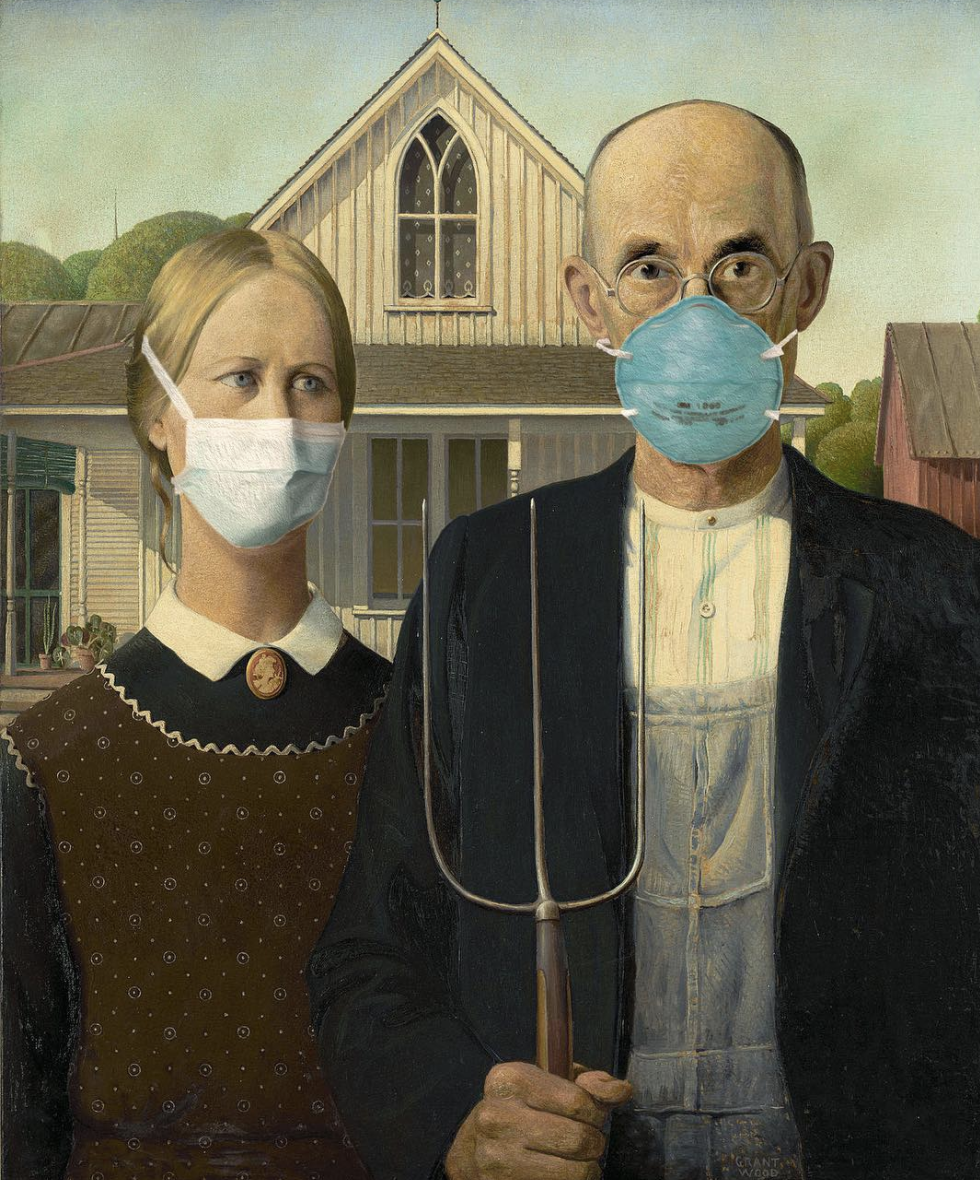

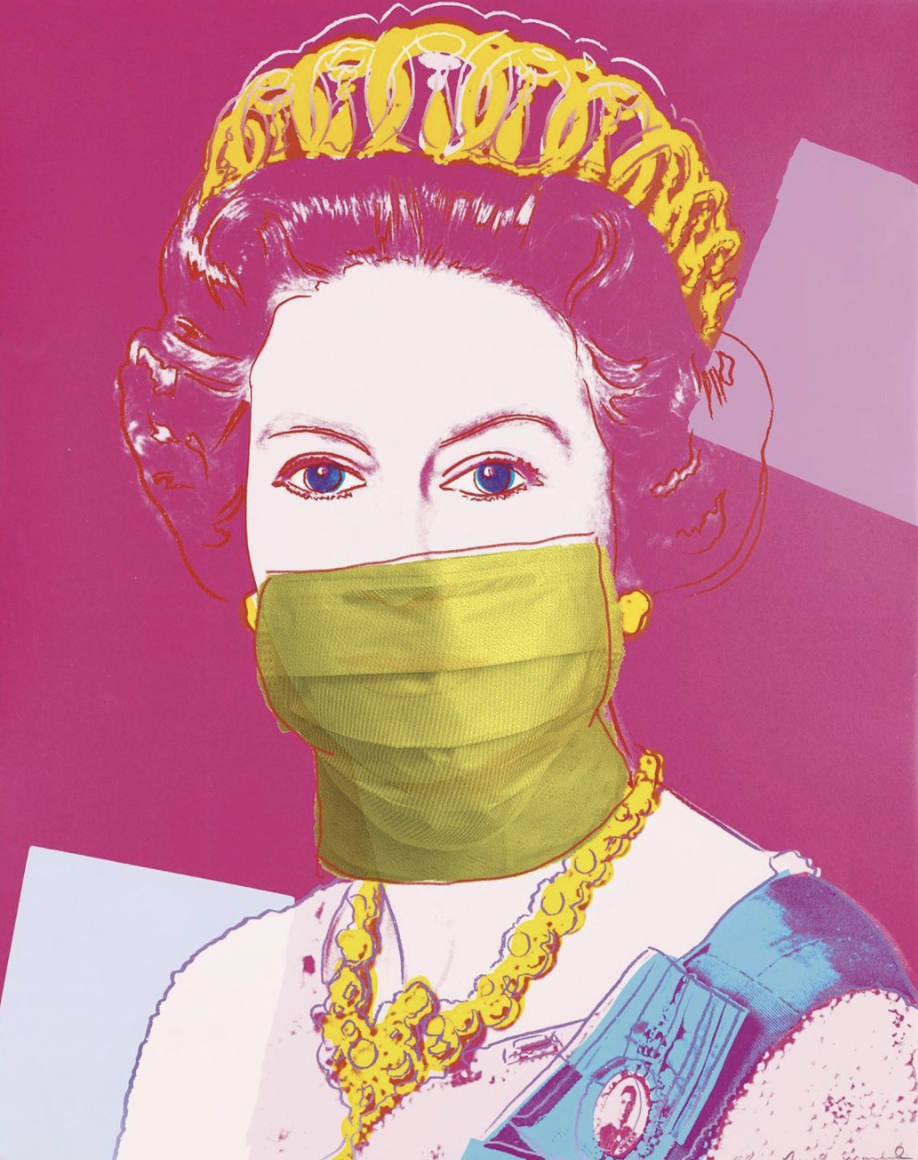

Banksy Strikes Again in London & Urges Everyone to Wear Masks

Banksy Debuts His COVID-19 Art Project: Good to See That He Has TP at Home

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.