The state of virtual and augmented reality technology has reached the threshold of a time in which VR meetings will be the norm. Apart from other applications, this may soon allow consumers to stroll through virtual aisles rather than clicking boxes on a screen, picking up products and viewing them from every angle. Still, designers recognize that an essence of the human experience is lost without the sense of touch. There may even be a future in which we wear clothes with haptic feedback systems embedded in them, to feel the pages of a virtual book beneath our fingers…

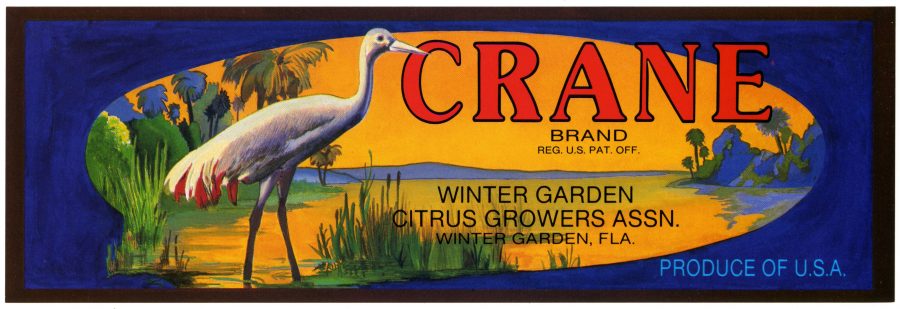

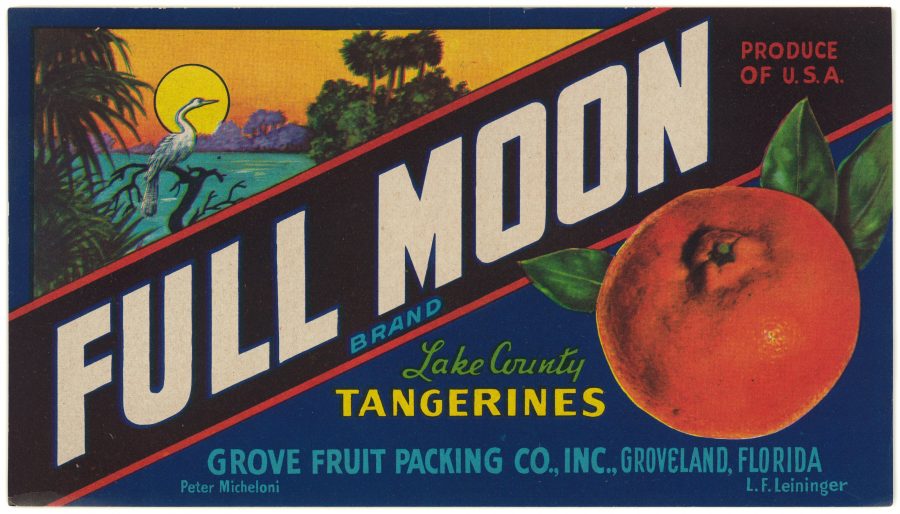

Yet our slow transition from the physical to the virtual world leaves out intangibles. Something is lost from both. Big box stores still devote significant floor space to books and records, for example. But I submit that a glossiness prevails in print design, perhaps a consequence of competing with screens. There’s a wabi-sabi quality to browsing a used bookstore or record shop in person, thumbing through an old collection of vintage paperbacks and LPs, that cannot be simulated or enhanced in any way. On the internet, however, where video is king, it can be made the subject of some hypnotic video art.

As the sensible majority of us are hopefully staying put for the long haul (if we can), we may find ourselves curiously edified by the video art of Henning M. Lederer. We’ve previously featured Lederer’s animations of mid-century minimalist book covers and vintage psychology and philosophy books. He turns the abstract geometric patterns beloved by book and record company designers of the latter half of the 20th century into moving images that hint at how proper cover design can set the imagination whirring (even if it’s a cover design for Basic Accounting).

If Lederer’s mesmerizing videos simulate anything, it’s the experience of wandering into a used bookstore next to a liberal arts college—full of professors’ fascinatingly outdated hand-me-downs—after having ingested a small quantity of LSD. Maybe you’ll have a slightly different association. But the point is that Lederer’s art suggests a scenario rather than attempting to recreate one. His studies of modernist cover designs also recall Marcel Duchamp’s Rotoreliefs, conceptual art pieces intended for popular use as optical illusions.

Duchamp’s spinning disks became features of early Surrealist cinema, iconic symbols of dreams on film. There is a mysterious opacity to his physical objects onscreen, just as Lederer’s book and record covers seem to have a weight of their own, a use of digital technology to highlight the strange uniqueness of physical objects, rather than their endless reproducibility.

Related Content:

157 Animated Minimalist Mid-Century Book Covers

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness