By their color palettes, by their dramatic structures, by their shot lengths, by the frequency and variety of their characters’ swearing: film enthusiasts have found ways to analyze just about every aspect of film. But only recently has the world of film analysis seen a large-scale study of dialogue by gender and age — in fact, the largest-scale study of dialogue by gender and age yet — undertaken by a new site called Polygraph, “a publication that explores popular culture with data and visual storytelling.” They wanted to put to the data test part of the notion, widely expressed in opinion pieces, that “white men dominate movie roles.”

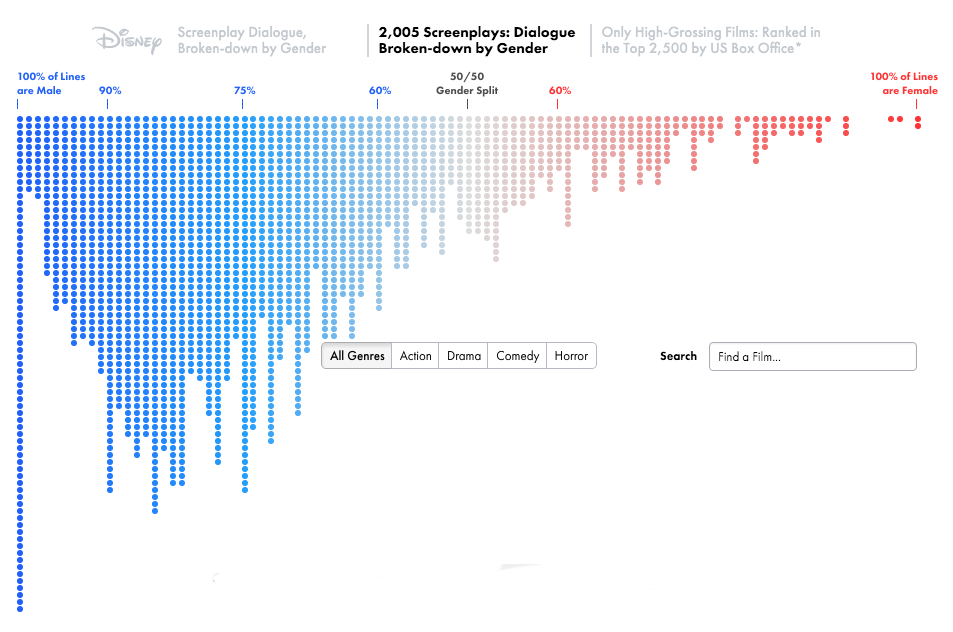

“We Googled our way to 8,000 screenplays and matched each character’s lines to an actor,” write Polygraph’s Hannah Anderson and Matt Daniels. “From there, we compiled the number of words spoken by male and female characters across roughly 2,000 films, arguably the largest undertaking of script analysis, ever.” They present their quantitative results with great visual clarity, and you can view them for three distinct areas of cinema territory: just the 2,000 screenplays the study focused on; only high-grossing films at the American box office; and only Disney movies (known, of course, for their abundance of princesses, with or without many lines).

“Across thousands of films in our dataset,” they write, “it was hard to find a subset that didn’t over-index male. Even romantic comedies have dialogue that is, on average, 58% male. For example, Pretty Woman and 10 Things I Hate About You both have lead women (i.e., characters with the most amount of dialogue). But the overall dialogue for both films is 52% male, due to the number of male supporting characters.” And as far as age, “dialogue available to women who are over 40 years old decrease substantially. For men, it’s the exact opposite: there are more roles available to older actors.”

Depending on what kind of films you watch, this may well jibe with your viewing experience: mainstream stories have long tended to favor macho and often mature protagonists, and the antagonists they defeat in man-to-man combat have sometimes reached advanced ages indeed (all the more time, presumably, in which to have mastered the art of villainy, especially of the one-last-grand-speech-before-I-destroy-the-world variety). The women, and usually young women, featured in such pictures, when they appear at all, have to do much of their communication nonverbally.

This all supports a complaint I’ve long had about the movies, mainstream or otherwise: over a century in existence, and they’ve hardly touched the vast creative space available to them. The all-female Ghostbusters coming this summer will surely do its small part to rectify the lack of woman-delivered dialogue on the silver screen, but the depth of the deficiency, as revealed by Polygraph, suggests we could do with a few all-female Glengarry Glen Rosses as well.

Related Content:

An Ambitious List of 1400 Films Made by Female Filmmakers

10 Tips From Billy Wilder on How to Write a Good Screenplay

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.