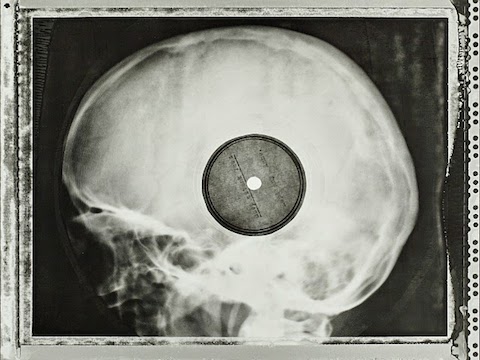

A catchy tribute to mid-century Soviet hipsters popped up a few years back in a song called “Stilyagi” by lo-fi L.A. hipsters Puro Instinct. The lyrics tell of a charismatic dude who impresses “all the girls in the neighborhood” with his “magnitizdat” and guitar. Wait, his what? His magnitizdat, man! Like samizdat, or underground press, magnitizdat—from the words for “tape recorder” and “publishing”—kept Soviet youth in the know with surreptitious recordings of pop music. Stilyagi (a post-war subculture that copied its style from Hollywood movies and American jazz and rock and roll) made and distributed contraband music in the Soviet Union. But, as a recent NPR piece informs us, “before the availability of the tape recorder and during the 1950s, when vinyl was scarce, ingenious Russians began recording banned bootleg jazz, boogie woogie and rock ‘n’ roll on exposed X‑ray film salvaged from hospital waste bins and archives.” See one such X‑ray “record” above, and below, see the fascinating process dramatized in the first scene of a 2008 Russian musical titled, of course, Stilyagi (translated into English as “Hipsters”—the word literally means “obsessed with fashion”).

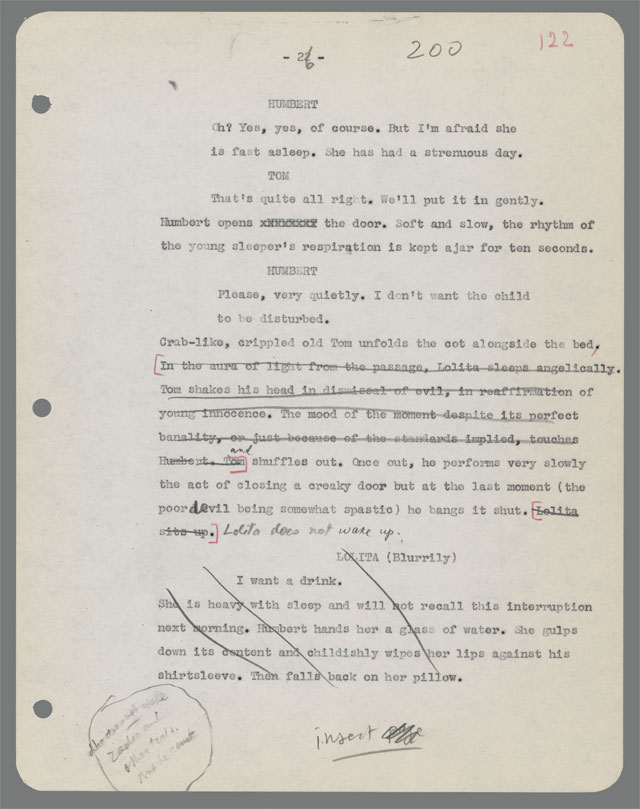

These records were called roentgenizdat (X‑ray press) or, says Sergei Khrushchev (son of Nikita), “bone music.” Author Anya von Bremzen describes them as “forbidden Western music captured on the interiors of Soviet citizens”: “They would cut the X‑ray into a crude circle with manicure scissors and use a cigarette to burn a hole. You’d have Elvis on the lungs, Duke Ellington on Aunt Masha’s brain scan….” The ghoulish makeshift discs sure look cool enough, but what did they sound like? Well, as you can hear below in the sample of Bill Haley & His Comets from a “bone music” album, a bit like old Victrola phonograph records played through tiny transistor radios on a squonky AM frequency.

Dressed in fashions copied from jazz and rockabilly albums, stilyagi learned to dance at underground nightclubs to these tinny ghosts of Western pop songs, and fought off the Komsomol—super-square Leninist youth brigades—who broke up roentgenizdat rings and tried to suppress the influence of bourgeois Western pop culture. According to Artemy Troitsky, author of Back in the USSR: The True Story of Rock in Russia, these records were also called “ribs”: “The quality was awful, but the price was low—a rouble or rouble and a half. Often these records held surprises for the buyer. Let’s say, a few seconds of American rock ’n’ roll, then a mocking voice in Russian asking: ‘So, thought you’d take a listen to the latest sounds, eh?, followed by a few choice epithets addressed to fans of stylish rhythms, then silence.”

But they weren’t all cruel censor’s jokes. Thanks to a company called Wanderer Records, you can own a piece of this odd cultural history. Roentgenizdat records, like the scratchy Bill Haley or the Tony Bennett “Lullaby of Broadway” disc sampled above, go for somewhere between one and two hundred bucks a piece—fair prices, I’d say, for such unusual artifacts, though of course wildly inflated from their Cold War street value.

See more images of bone music records over at Laughing Squid and Wired co-founder Kevin Kelly’s blog Street Use, and above dig some historical footage of stilyagi jitterbugging through what appears to be a kind of Soviet training film about Western influence on Soviet youth culture, produced no doubt during the Khrushchev thaw when, as Russian writer Vladimir Voinovich tells NPR, things got “a little more liberal than before.”

Related Content:

How to Spot a Communist Using Literary Criticism: A 1955 Manual from the U.S. Military

Louis Armstrong Plays Historic Cold War Concerts in East Berlin & Budapest (1965)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness