Koko the Gorilla, who celebrates her 43rd birthday today, keeps pretty down-to-earth company for a celebrity. While others court the paparazzi with their public canoodling and high profile Twitter feuds, Koko’s most comfortable hanging with non-marquee-name kittens and pals Penny Patterson and Ron Cohn, the human doctors who’ve headed her caregiving team for the past 41 years.

Her privacy is closely guarded, but there have been a handful of times over the years when her name has been linked to other celebs…

Above, actor William Shatner recalls how, as a younger man, he called upon her in her quarters. He was nervous, approaching submissively, but determined not to retreat. “I love you, Koko,” he told her. “I love you.”

She responded by gripping a part of his anatomy that just happens to be one of the thousand or so words that comprise her American Sign Language vocabulary. One that takes two hands to sign…

Their time was fleeting, but as evidenced below, the connection was intense.

Comedian Robin Williams also claims to have shared “something extraordinary” with Koko. Their flirtation seems innocent enough, despite Williams’ NSFW description of their encounter, below. (He undercuts his credibility by referring to her as a “silverback”.)

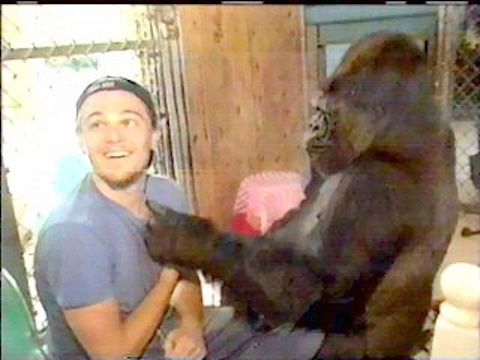

Leonardo DiCaprio is yet another famous admirer to be caught on camera with Koko. Is it any wonder that she embodies all of the qualities he claims to look for in a potential love interest: “humility, a sense of humor and not a lot of drama”? No word as to how the Titanic hunk measures up against the qualities Koko looks for in a mate, though footage of their one and only meeting has been known to get fans fantasizing in the comments section: “I wish I was that gorilla ;) lol I looooooooooooooooove u Leo”

From the lady’s perspective, Koko’s sweetest celebrity encounter was almost certainly with her favorite, the late children’s television host, Fred Rogers. She removed his shoes and socks, he studied her lips, love was a primary topic and yet their time together does not invite prurient speculation. I can’t think of another human male as deserving of her affection.

Related Content:

Planet of the Apes: A Species Misunderstood

Ayun Halliday invites you to read her thoughts on another July 4 birthday on Rewire Me. Follow her @AyunHalliday