Halloween looms.

Have we got a tarot deck for you!

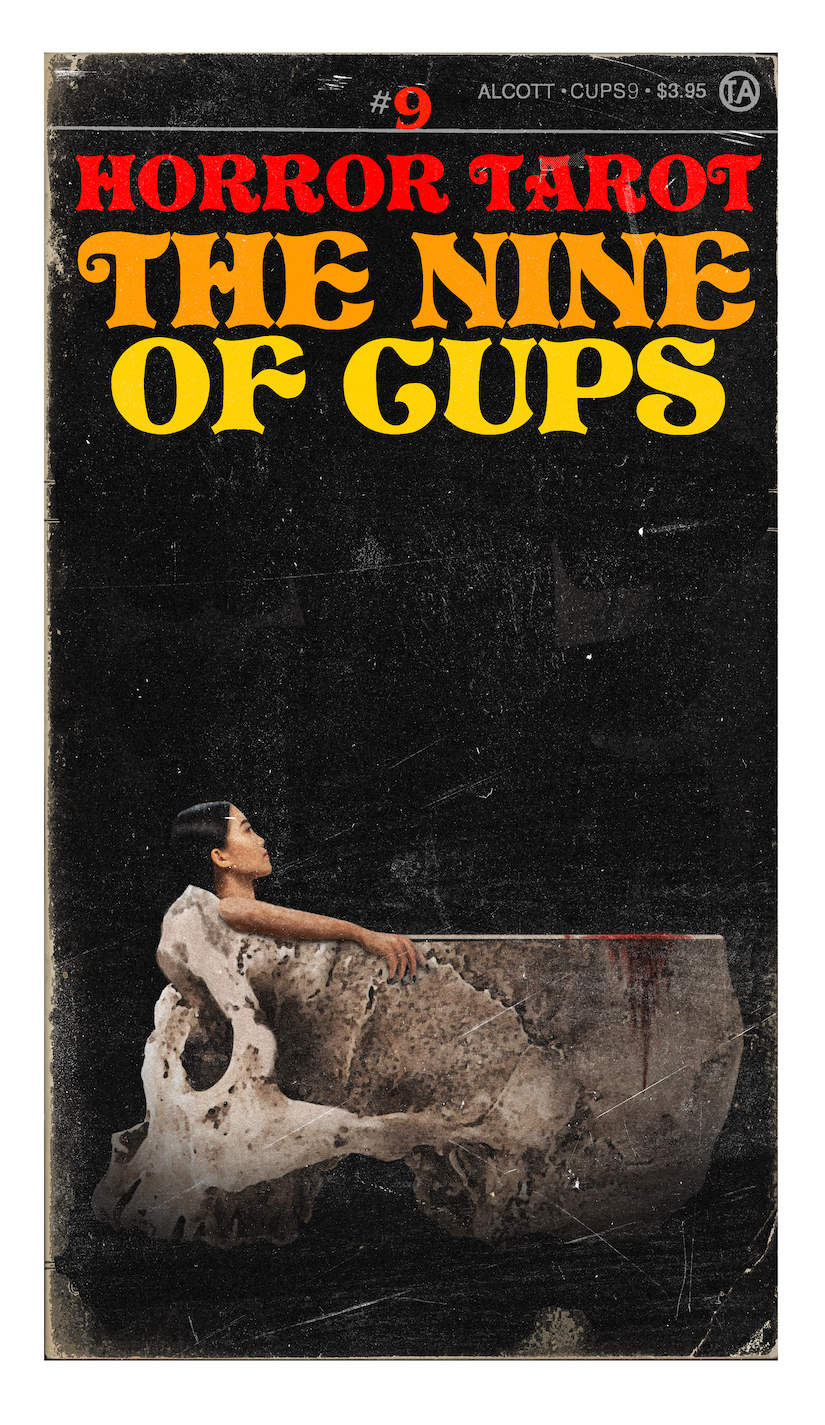

Todd Alcott, the mad scientist responsible for Open Culture’s favorite midcentury graphic mashups, infuses his Horror Tarot with a century’s worth of hair-raising, spine-tingling imagery.

The artist admires the genre’s capacity for conveying subversive messages, explaining that “horror is where we think about the unthinkable and revel in the things that are bad for us:”

Drama can exalt the finest in humanity, but horror shows us who we really are. From The Golem to Frankenstein to The Shining to The Silence of the Lambs, horror uses metaphor to explore the darkest and most unforgivable aspects of human nature.

As he did with his Pulp Tarot deck, Alcott put in hundreds of research hours, studying movie posters, pulp magazines, fan mags, paperback books, and classic comics to get a feel for period design trends and execution:

I love seeing the different developments in printing, from etching to lithography to silkscreens to offset printing. All those different methods of creating images, all ridiculously complicated back then, are now taken care of easily with a few mouse clicks. In my own perverse way, I want to bring those days back. I want to see the flaws in the process, I want to see the limitations of reproduction, and, most of all, I want to be able to feel the paper the images are printed on.

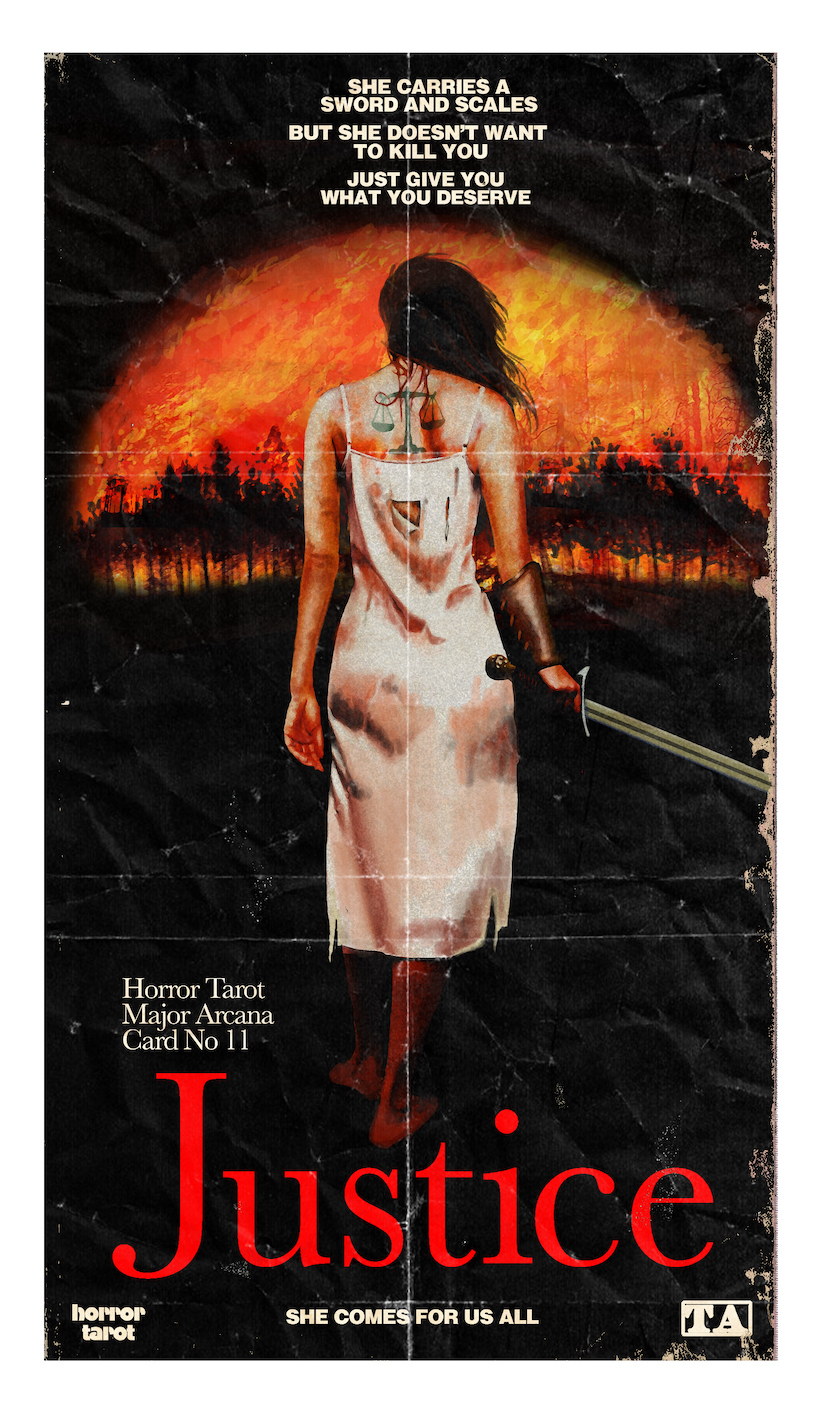

The cards of the Major Arcana are inspired by film posters spanning the silent era to the present day. Each card has close ties to Horror Tarot Studios, a fictional production company that purports to have been in business since the dawn of the motion picture.

The Justice card references marketing tactics for gritty 70s drive-in staples like Last House on the Left and I Spit on Your Grave. The deck’s instruction booklet contains a few anecdotes about the production of these movies, a helpful bit of context for those who might have missed (or skipped) that fertile era of women’s revenge pictures:

I wanted the Horror Tarot Justice to be someone the reader can root for, even if they’re horrified by what Justice promises: not death, but “what you deserve.”

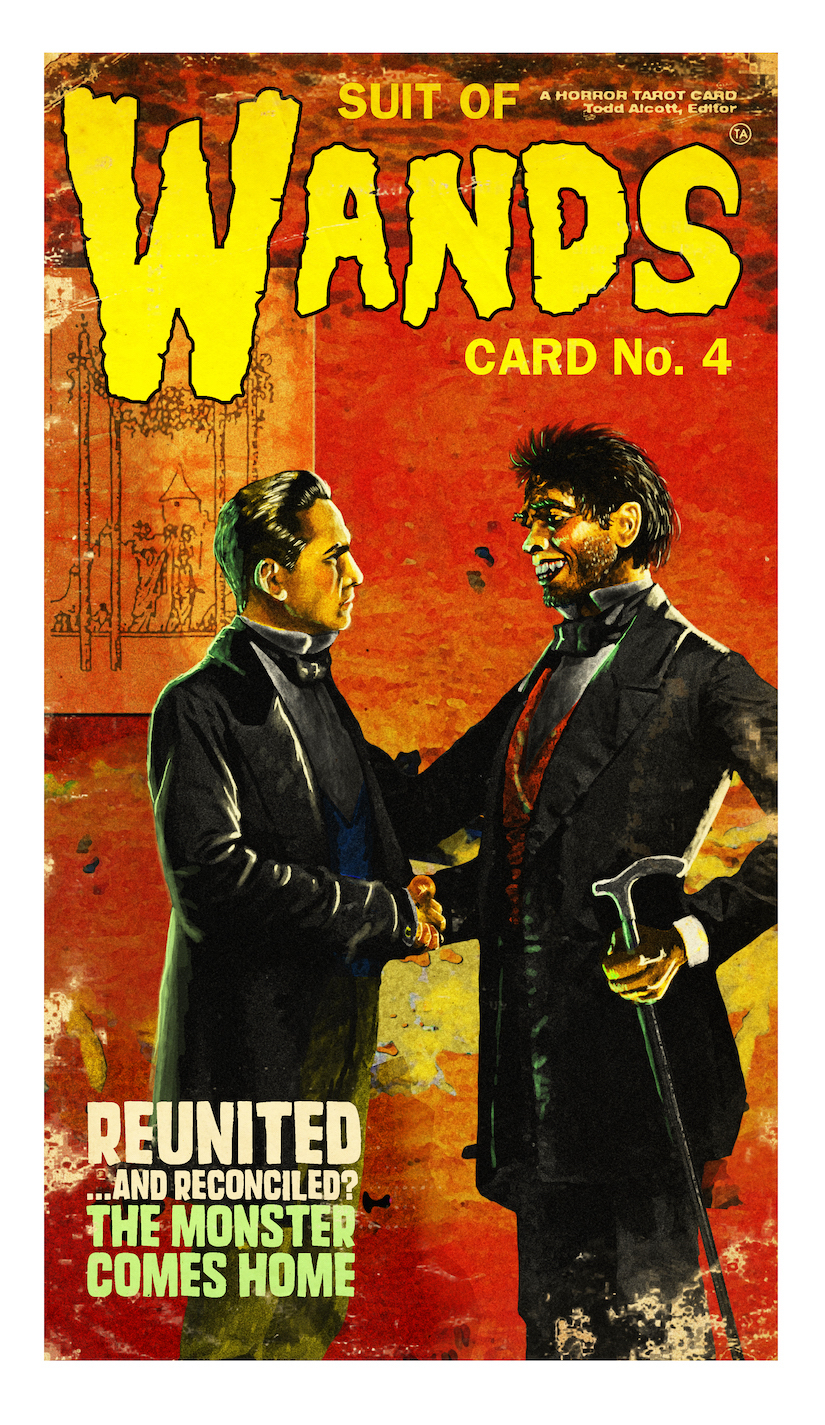

Famous Monsters of Filmland, a prime pre-internet resource for horror fans, was Alcott’s jumping off place for the Minor Arcana’s Suit of Wands.

You may have no knowledge of that seminal publication, but you’d probably recognize some of the cover artwork by painter Basil Gogos, featuring such MVPs as Frankenstein’s monster, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the Phantom of the Opera and Dracula. Alcott says that many of Gogos’ iconic monster portraits are more deeply ingrained in the public memory than the art the studios chose to promote their movies:

…for the Suit of Wands I wanted to create a series of portraits done in his style, featuring characters he never got around to painting. The Four of Wands is a card about homecoming and reconciliation, and I had the idea to paint Frederick March’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde as two separate men, meeting for the first time in a back alley in Victorian London.

A homecoming doesn’t necessarily require a physical return to a physical home — it can be completely internal. I wanted to show Dr. Jekyll coming to terms with his inner struggle.

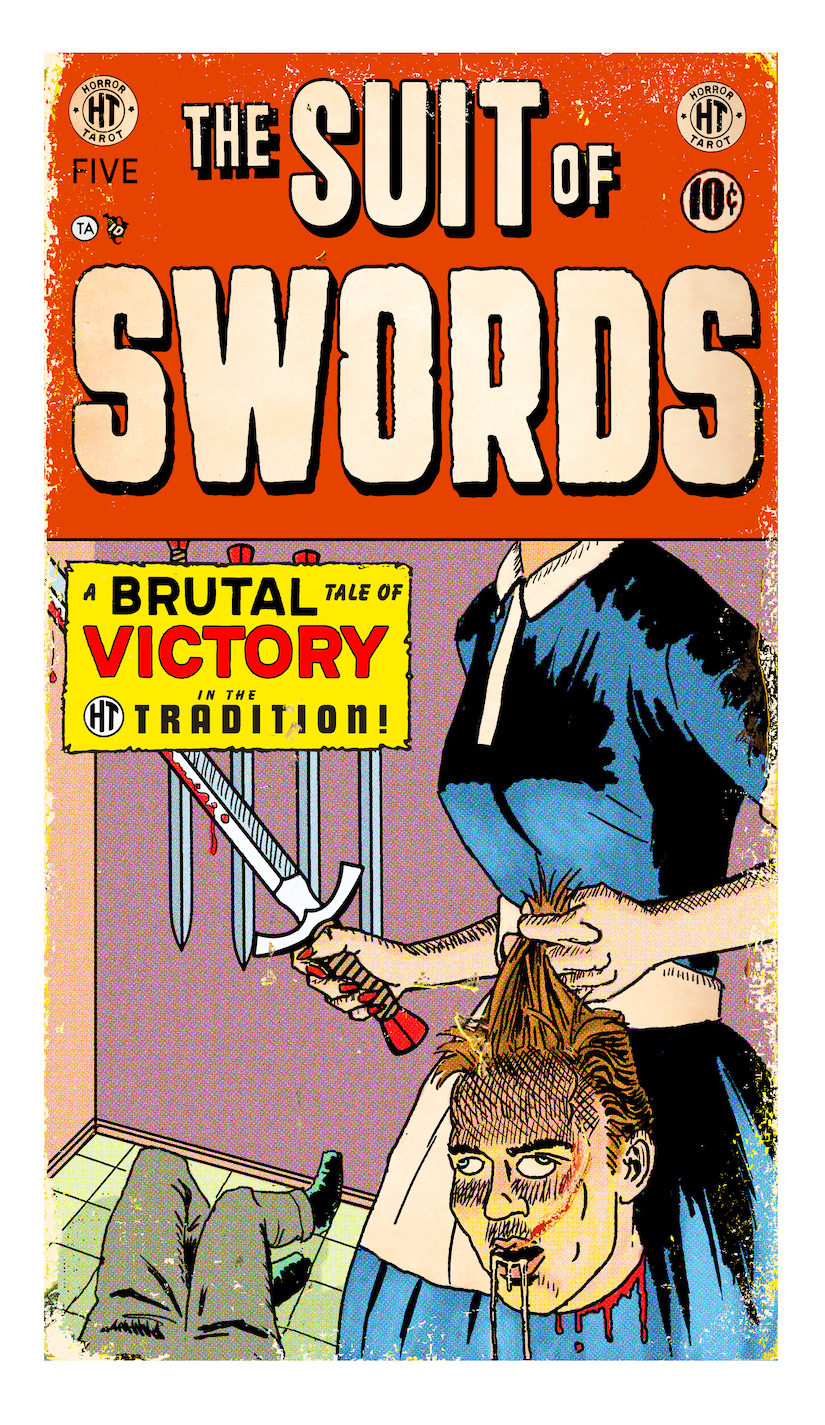

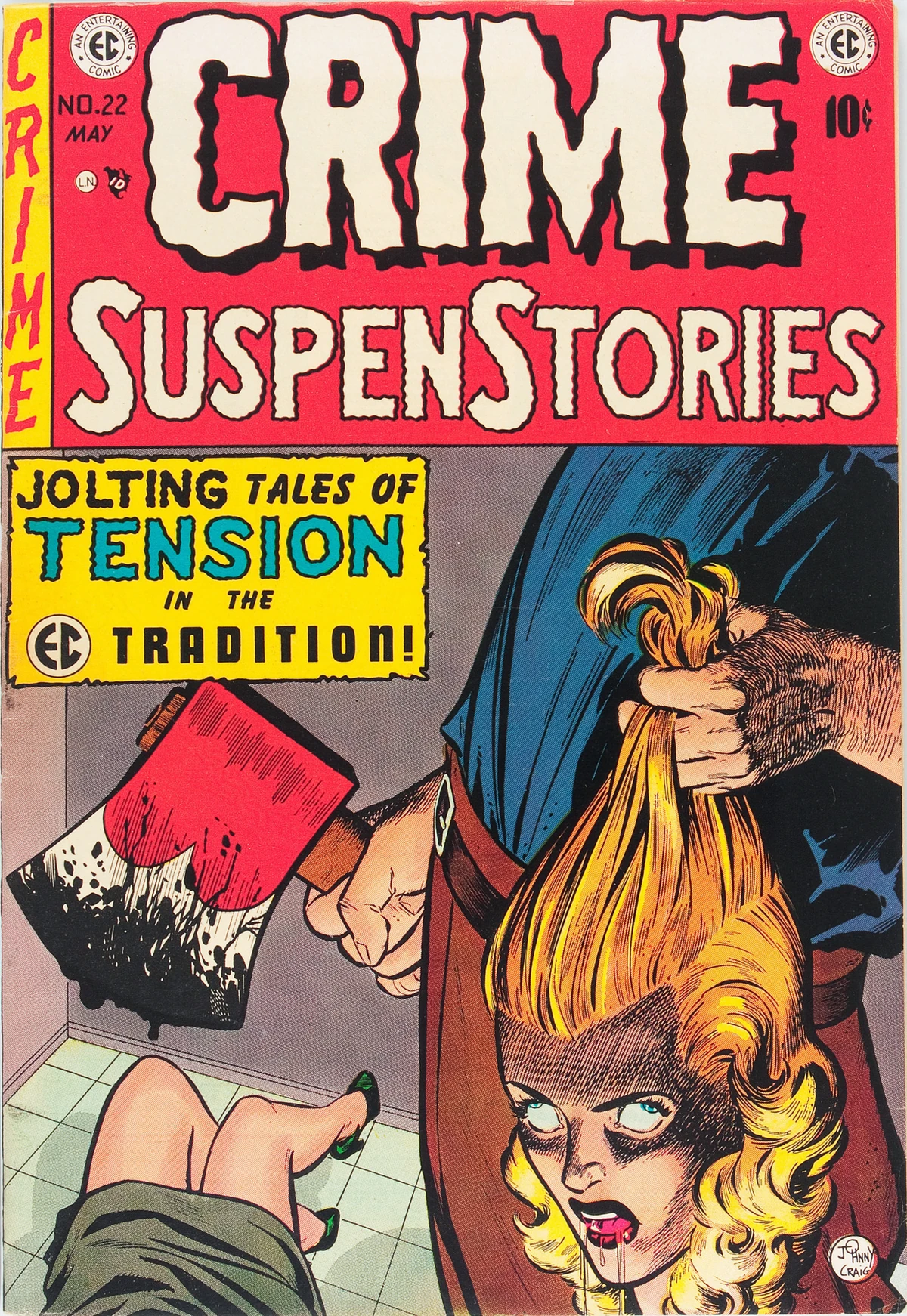

The Suit of Swords recreates the look of another indelible horror trope — the EC comics of the 1950s:

These comics were so lurid and perverse that they actually sparked a congressional investigation, which ended up putting them out of business. Again, before the internet, this is what horror fans had available to them, and comics publishers had to keep pushing the limits of what was acceptable in order to stay ahead of the competition.

For the Five of Swords, I parodied and gender-swapped the infamous cover of Crime SuspenStories #22. The Five of Swords is a card about being a bad winner, about gloating at your opponent’s defeat, about overkill. I figured that a housewife murdering her husband and then beheading him with a sword counted as overkill.

Todd Alcott’s Horror Tarot is available here.

Related Content

Watch the German Expressionist Film, The Golem, with a Soundtrack by The Pixies’ Black Francis

Behold the Sola-Busca Tarot Deck, the Earliest Complete Set of Tarot Cards (1490)

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.