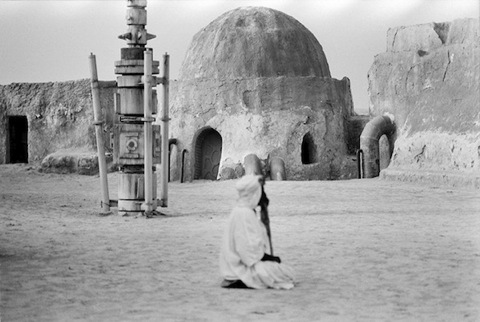

Making a movie? Need to shoot some large-scale desert scenes? You might consider taking your production to North Africa, where you’ll find not only a great many acres of sand, but will follow in the footsteps of some of the twentieth century’s highest-profile filmmakers. Just above, you see a picture of one of the many Star Wars sets still standing in Tozeur, Tunisia, 36 years after the shoot. New York photographer Rä di Martino has taken it upon herself to determine the locations and collect images of these cinematic ruins in the projects “No More Stars” and “Every World’s a Stage.” Given the surprisingly sound condition of some of these sets — that dry air must have something to do with it — I foresee an entrepreneurial opportunity in the vein of all those New Zealand Lord of the Rings fan tours.

Even if Star Wars doesn’t get you excited enough to book a trip to Tunisia, a visit to Morocco may still interest you. Di Martino’s short Petite histoire des plateaux abandonnès (Short History of Abandoned Sets) seeks out more such long-silent fake towns, fortresses, and gas stations around Ouarzazate, originally used for everything from cheap horror movies to Lawrence of Arabia. There, a group of kids recites, deadpan, scenes from the various productions that swung through town well before they were born. These surviving chunks of artifice, meant only for the camera, have found the camera again — or, rather, the camera has found them — with results that now look more interesting than many of the major films that commissioned them.

Related Content:

The Making of The Empire Strikes Back Showcased on Long-Lost Dutch TV Documentary

Hundreds of Fans Collectively Remade Star Wars; Now They Remake The Empire Strikes Back

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.