As summer approaches, let us look to Allen Ginsberg when we we feel discouraged by our lack of bikini-body. The author of “Sunflower Sutra” didn’t shy away from having his evolving physique documented shirtless or nude. Narrow minded beauty arbiters be damned. The man was well equipped for tenement living on the Lower East Side of New York in the era before air-conditioning.

Another Ginsbergian tactic for embracing the season’s heat: borscht. Unlike Rudolph Nureyev’s or Cyndi Lauper’s favorite from Veselka, the round-the-clock Ukrainian diner a few blocks from Ginsberg’s East Village home, Ginsberg’s borscht is vegetarian and cold. See the transcription of Ginsberg’s handwritten recipe below:

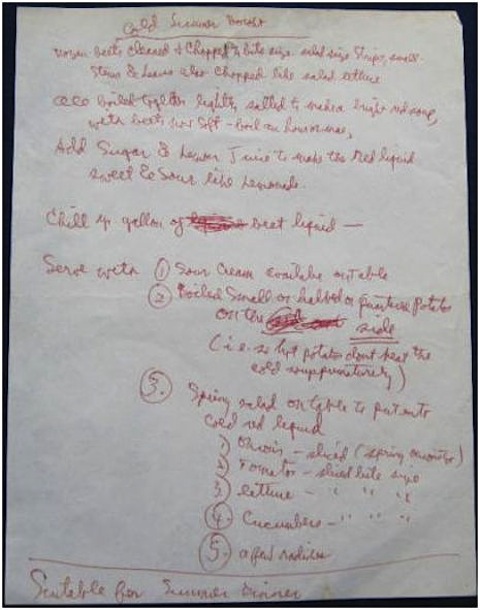

COLD SUMMER BORSCHT

Dozen beets cleaned & chopped to bite size salad-size Strips

Stems & leaves also chopped like salad lettuce

All boiled together lightly salted to make a bright red soup,

with beets now soft — boil an hour or more

Add Sugar & Lemon Juice to make the red liquid

sweet & sour like Lemonade

Chill 4 gallon(s) of beet liquid -

Serve with (1) Sour Cream on table

(2) Boiled small or halved potato

on the side

(i.e. so hot potatoes don’t heat the

cold soup prematurely)

(3) Spring salad on table to put into

cold red liquid

1) Onions — sliced (spring onions)

2) Tomatoes — sliced bite-sized

3) Lettuce — ditto

4) Cucumbers — ditto

5) a few radishes

__________________________________

Suitable for Summer Dinner

Cold Summer Borscht was but one of many soups to remerge from Ginsberg’s twelve-gallon stockpot. Read about his final batch here. Bon Apetit.

Related Content:

Allen Ginsberg Reads a Poem He Wrote on LSD to William F. Buckley

Allen Ginsberg Reads His Famously Censored Beat Poem, Howl

“Expansive Poetics” by Allen Ginsberg: A Free Course from 1981

Ayun Halliday is the author of seven books including Dirty Sugar Cookies: Culinary Observations, Questionable Taste. Follow her @AyunHalliday