Another immigrant comin’ up from the bottom

His enemies destroyed his rep, America forgot him…

Holler if you can remember a time when few Americans were well-versed enough in founding father Alexander Hamilton’s origin story to recite it in rhyme at the drop of a hat.

Believe it or not, as recently as the summer of 2015, when Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Hamilton: An American Musical exploded on Broadway, Hamilton the man was, as the Tony award winning lyrics above suggest, largely forgotten, a relic whose portrait on the $10 bill aroused little curiosity.

Back then, Hamilton was perhaps best known as the hapless soul embodied by Michael Cera in the web series Drunk History.

Ron Chernow’s 2005 biography served up a more nuanced portrait to readers with the stamina to make it through his massive tome.

That’s the book Miranda famously took along on vacation in the period between his musical In the Heights’ Broadway and Off-Broadway runs.

The rest, as they say, is history.

As is the above video, in which a 29-year-old Miranda performs The Hamilton Mixtape for President Obama, the First Lady, and other luminaries as part of a White House evening of poetry, music, and spoken word.

There’s your Hamilton (the musical) origin story.

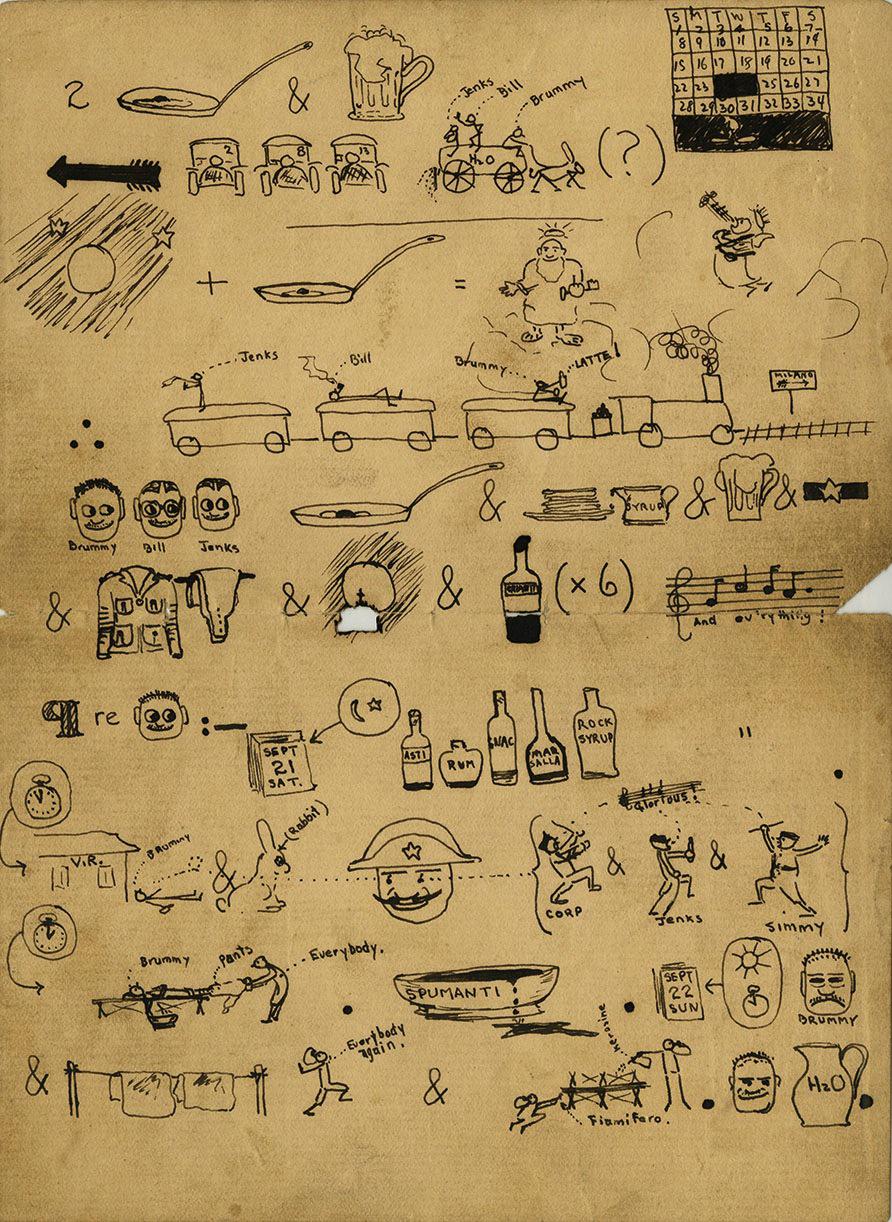

Its creator initially conceived of it as a hip hop concept album in which celebrated rappers would give voice to different historical characters.

Music director Alex Lacamoire’s jubilant expression at the White House piano confirms that they had some inkling that they were on to something very big.

A few months later, Miranda reflected on the experience in an interview with Playbill:

The whole day was a day that will exist outside any other day in my life. Any day that starts with you sharing a van to the White House with James Earl Jones is going to be a crazy day! I was the closing act of the show and I had never done this project in public before so I was already nervous. I looked at the President and the First Lady only once and when I looked at him he was whispering something to her and I couldn’t let that get to me. Afterwards, George Stephanopoulos came up to me and said, “The President is back there talking about your song, he’s saying ‘Where is (Secretary of the Treasury) Timothy Geitner? We need him to hear the Hamilton rap!’” To hear that the President enjoyed the song was a real dream come true.

The Obamas enjoyment was such that they appeared in a pre-taped segment to introduce the Hamilton cast at the 2016 Tony awards (a tough year for any other musical unlucky enough to have debuted in the same period as this juggernaut).

They also hosted a Hamilton workshop for DC-area youth, for which the Broadway cast traveled down on their day off, performing the opening number out of costume. Biographer Ron Chernow was in the front row for that one, as Obama remarked that “Hamilton is the only thing Dick Cheney and I agree on.”

(“Dick Cheney attended the show tonight,” Miranda tweeted after Cheney’s visit. “He’s the OTHER vice-president who shot a friend while in office.” Current Vice President Mike Pence also took in a performance shortly before his swearing in, though his appearance was met with a much less pithy response.)

As for The Hamilton Mixtape, many of Miranda’s dream rappers turned out for its recording, though the tracks they laid down diverge from the one performed live for the Obamas in 2009, which legions of adoring fans can chant along to thanks to the musical’s overwhelming popularity. Instead, this mixtape’s contributing artists were invited to reimagine and expand upon the themes of the play—immigration, ambition, and stubble—placing them in an explicitly 21st-century context.

Listen to The Hamilton Mixtape and the original cast recording of Hamilton for free on Spotify.

Related Content:

Lin-Manuel Miranda & Emily Blunt Take You Through 22 Classic Musicals in 12 Minutes

A Whiskey-Fueled Lin-Manuel Miranda Reimagines Hamilton as a Girl on Drunk History

Hamilton’s Lin-Manuel Miranda Creates a 19-Song Playlist to Help You Get Over Writer’s Block

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She has yet to win the Hamilton lottery. Join her in New York City for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain, this March. Follow her @AyunHalliday.