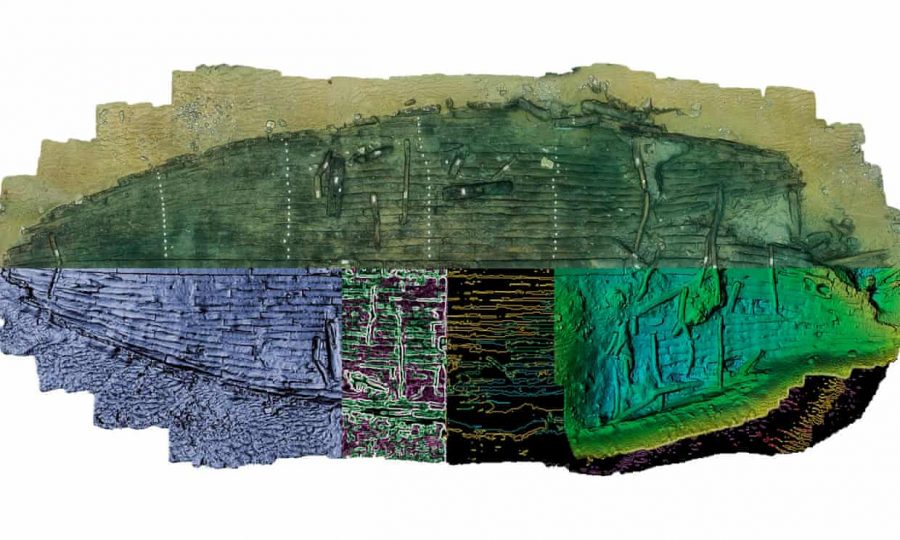

Some people hate the massive concrete buildings known as Brutalist, but they at least approve of the style’s name, resonant as it seemingly is with associations of insensitive, anti-humanist bullying. Those who love Brutalism also approve of the style’s name, but for a different reason: they know it comes from the French béton brut, referring to raw concrete, that material most generously used in Brutalist buildings’ construction. We’ve all seen Brutalist architecture, massively embodied by Boston City Hall, London’s Barbican Centre, UC Berkeley’s Wurster Hall, the University of Toronto’s Robarts Library, FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C., or any other of the examples that have stood since the style’s 1960s and 70s heyday. But now, as more get slated for demolition each year, it has fallen to Brutalism’s enthusiasts to defend an architecture easily seen as indefensible.

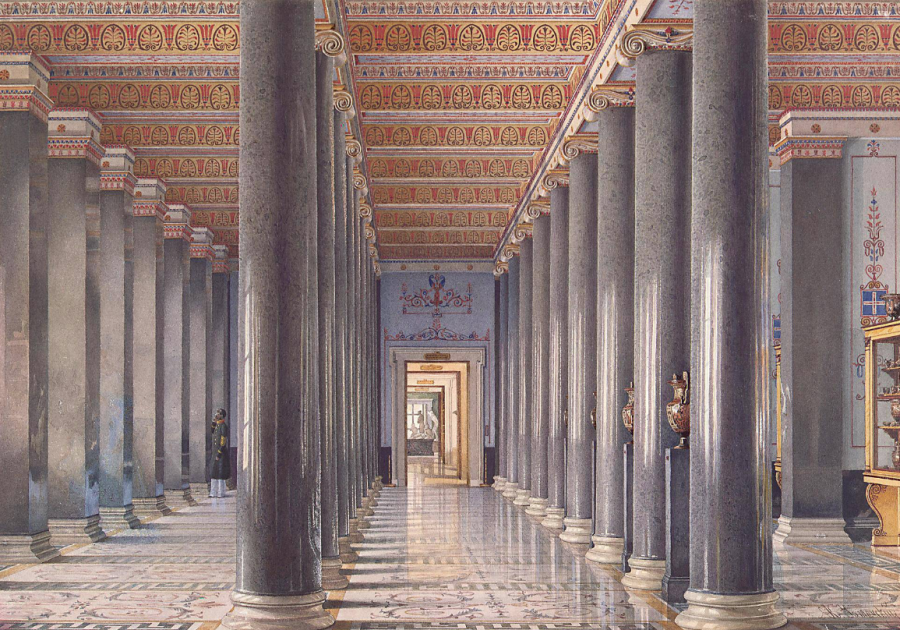

The aesthetic of Brutalism, says host Roman Mars in an episode of the podcast 99% Invisible on the style, “can conjure up associations with bomb shelters, Soviet-era or ‘third-world’ construction, but as harsh as it looks, concrete is an utterly optimistic building material.” In the 1920s “concrete was seen as being the material that would change the world. The material seemed boundless — readily available in vast quantities, and concrete sprang up everywhere — on bridges, tunnels, highways, sidewalks, and of course, massive buildings.”

It “presented the most efficient way to house huge numbers of people, and government programs all over the world loved it — particularly Soviet Russia, but also later in Europe and North America.” Philosophically, “concrete was seen as humble, capable, and honest—exposed in all its rough glory, not hiding behind any paint or layers.”

However noble the intentions behind these works of architecture, though, it didn’t take humanity long to turn on Brutalism. Part of the problem had to do with the disrepair into which many of the highest-profile Brutalist buildings — social housing complexes, transit centers, government offices — were allowed to fall immediately after the ideologies that drove their construction passed out of favor. But Brutalism also fell victim to a predictable cycle of fashion: as architecture critics often point out, the public of any era consistently admires hundred-year-old buildings, but condemns (often literally) fifty-year-old buildings. New Yorkers still lament the loss of their grand old Penn Station, but its ornate Beaux-Arts style no doubt looked as heavy-handed and out-of-touch to as many people in the early 1960s, the time of its demolition, as Brutalism does today.

What, then, is the case for Brutalist architecture? “It’s a sense of place. It’s a sense of the drama of the space that they surround,” says This Brutal World author Peter Chadwick the BBC clip at the top of the post. “It is sculpture. It’s gone beyond being just functional. It’s just beautiful sculpture that mirrors its environment.” In the DW Euromaxx video below, Deutsches Architekturmuseum curator Oliver Elser sees in Brutalism a valuable lesson for building today: “Make more from less. I think this way of thinking, spatial generosity with simpler materials, is a timely stance for architecture.” Architectural historian Elain Harwood calls Brutalism “a particular architecture for ambitious times gripped by a fervor for change. Whatever style you call it, the results are unique and have a heroic beauty than sets them apart from the architecture of any other era.” (In fact, some Brutalism enthusiasts who dislike the label have put up the term “Heroic” instead.)

Whatever the articulacy of Brutalism’s defenders, the most effective arguments for its preservation have been made with not words but images. Chadwick first made his mark with his This Brutal House accounts on Twitter and Instagram, and a search on the latter for the hashtag #brutalism reveals the astonishing range and intensity of the style’s 21st-century fandom. A fair few videos have also taken individual works of Brutalism as their subjects, from a reflexively loathed survivor like Boston City Hall to the unlikely upper-middle-class oasis of the Barbican Centre to a high-minded projects now under the wrecking ball like Robin Hood Gardens. Despite how many people seem happy to see Brutalist buildings go, some, like Australian architect Shaun Carter in his TEDx Sydney Salon talk below, remind us of the value of keeping our history concretized, as it were, in the built environment around us.

Bunkers, Brutalism and Bloodymindedness: Concrete Poetry writer Jonathan Meades puts it more forcefully: “The destruction of Brutalist buildings is more than the destruction of a particular mode of architecture. It is like burning books. It’s a form of censorship of the past, a discomfiting past, by the present. It’s the revenge of a mediocre age on an age of epic grandeur.” To his mind, it’s the destruction of evidence of “a determined optimism that made us more potent than we have become,” of the fact that “we don’t measure up against those who took risks, who flew and plunged to find new ways of doing things, who were not scared to experiment, who lived lives of perpetual inquiry.” If Brutalism has to go, it has to go because it reminds us that “once upon a time, we were not scared to address the Earth in the knowledge that the Earth would not respond, could not respond.”

Related Content:

Bauhaus, Modernism & Other Design Movements Explained by New Animated Video Series

1,300 Photos of Famous Modern American Homes Now Online, Courtesy of USC

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.