There are numerous ancient stories illustrating the gargantuan ego of the Emperor Nero. Some of these may rise to the level of historical character assassination. Nero did not, for example, fiddle while Rome burned. For one thing, the fiddle did not exist. For another, as the historian Tacitus records, although the emperor was miles away at his villa in Antium when the fires began, it’s said he returned to Rome and led relief efforts, paying for many of them out of his own pocket and housing the newly homeless in his garden.

But the story may have been rewritten to burnish Nero’s reputation. After the masses blamed him for starting the fire, he turned around and blamed the city’s Christians, Tacitus reports, staging elaborate spectacles of torture, burning, and dismemberment. Suetonius does record him as giving some sort of musical performance during the fires of 64 A.D., a rumor that had apparently taken hold among the people. Whatever part he played, and whatever truth there is to charges that he murdered the son of Claudius, one of his wives, and even his own mother, Nero clearly felt a pressing need to leave a different impression of himself—as a towering, bronze god-like figure nearly 100 feet high.

In the same year as the fires, he commissioned a colossal statue of himself as the sun god, inspired by the Colossus of Rhodes. The massive Nero held a rudder perched atop a globe, suggesting that his rule steered the course of the whole world. Nero killed himself before the statue was completed, but Pliny the Elder writes of seeing its creation in the studio of the sculptor, Zenodorus. It arose towering above his palace, the Domus Aurea, in 72 A.D., and in 127, Hadrian moved it near the Amphitheatrum Flavium, which subsequently became known in the statue’s honor as the Colosseum. It took up to 24 elephants to do the job, or so it’s said.

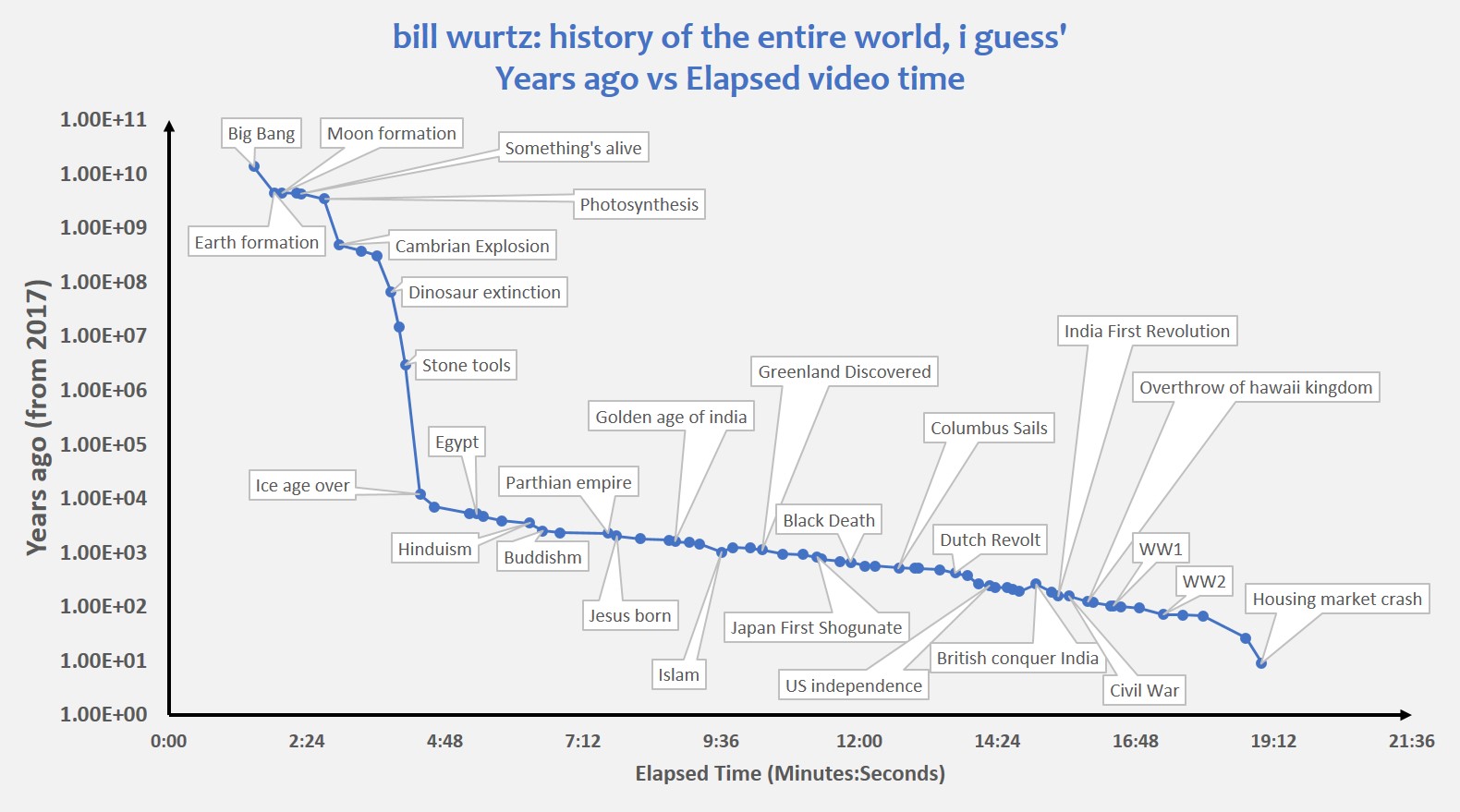

For the next few hundred years, until at least the sack of Rome by Alaric in 410 and a subsequent series of earthquakes, residents and visitors to the city walked beneath the looming Nero/Helios/Apollo statue, just fifty feet shy of the Statue of Liberty. It was depicted on medallions and gems. Now the statue is completely vanished, with nothing but a remnant of its pedestal remaining. But you can see it reconstructed, along with 27 other ancient Roman monuments, temples, baths, mausoleums, amphitheaters, arenas, etc.—many of them as grandiose and storied as the Colossus—in the thirty-minute video above.

No, it’s not like strolling the streets of ancient Rome. The blockily-rendered CGI recreations appear over contemporary video of the city, full of contemporary traffic and contemporary fashions. As in every historical recreation of antiquity, for which the sources are few and contradictory, we have to use our imaginations. The exercise is infinitely richer the more you learn about the vanished or ruined structures that once dominated the city. See the full list of ancient buildings and sculptures below.

0:10 Palatine Hill (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palatin…)

3:25 The Forum (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_F…)

5:22 Basilica of Maxentius (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilic…)

7:18 Temple of Vesta (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_…)

7:26 House of the Vestals (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_o…)

7:48 Temple of Castor and Pollux (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_…)

8:03 Temple of Caesar (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_…)

8:13 Basilica Aemilia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilic…)

8:40 Basilica Julia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basilic…)

9:17 Temple of Saturn (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_…)

10:56 Curia Julia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curia_J…)

12:18 Forum of Augustus (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forum_o…)

13:05 Forum of Nerva (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forum_o…)

13:47 Trajan’s Forum (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trajan%…)

14:54 Forum of Caesar (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Forum_o…)

15:29 Colosseum (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colosseum)

17:42 Temple of Venus and Roma (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_…)

18:59 Colossus of Nero and Meta Sudans (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colossu… -https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meta_Su…)

19:28 Baths of Caracalla (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baths_o…)

26:39 Pantheon (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pantheo…)

28:13 Stadium of Domitian (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stadium…)

29:23 Mausoleum of Augustus (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mausole…)

29:39 Circus Maximus (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Circus_…)

30:25 Sacred area (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Largo_d…)

31:21 Theatre of Pompey (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatre…)

31:56 Theatre of Marcellus (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theatre…)

32:05 Tiber Island (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiber_I…)

32:32 Mausoleum of Hadrian (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Castel_…)

Related Content:

An Interactive Map Shows Just How Many Roads Actually Lead to Rome

All the Roman Roads of Italy, Visualized as a Modern Subway Map

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness